Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

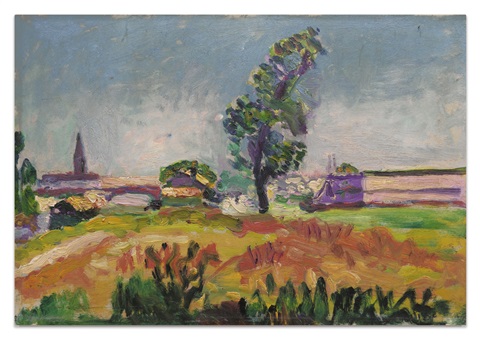

“Landscape of the Surroundings of Toulouse, the Pont des Demoiselles” captures a transitional moment in Henri Matisse’s development, when he had just left the Atlantic climates of Brittany and moved into the clearer, more saturated light of the French south. The subject is humble: a bridge crossing a quiet watercourse, a distant spire, a few low structures, and a tall, wind-bent tree commanding the middle of the picture. Yet from these plain ingredients Matisse composes a scene that vibrates with color and rhythm. Brushstrokes remain visible and directional. Greens and violets trade places with ochres and oranges. Space is built through the stacking of planes rather than through academic perspective. What results is not a descriptive topographical view but a living arrangement of forces—land, water, sky—translated into paint.

The Year 1898 and the Turn Toward the South

The late 1890s were a crucible for Matisse. After rigorous academic training and dark, weighty still lifes, he broke away to paint outdoors on the Breton coast in 1896 and 1897. Those campaigns taught him to reduce nature to firm silhouettes and to rely on warm–cool relations rather than tight modeling. In 1898 he explored more southern locales, including Toulouse, where light is drier and shadows carry violets rather than browns. “Landscape of the Surroundings of Toulouse, the Pont des Demoiselles” belongs to this moment of recalibration. The palette lifts. Whites are no longer merely neutral—they become carriers of light. Color begins to shoulder structural responsibility, foreshadowing the Fauvist leap a few years later.

Motif and Vantage

The motif is a view across flat country toward a low bridge and church spire. A tall, slender tree rises almost at center, slightly off to the right, tilting with the wind. The vantage point is modest and close to the ground, as if the painter were standing on a path at field’s edge. This low stance gives the foreground bands of earth and scrub unusual presence and creates a sense of walking into the scene. The distant architecture remains schematic—little more than silhouettes and colored blocks—so that the attention stays on the exchange between tree, bridge, field, and sky.

Composition as Interlocking Bands and a Vertical Counter

The picture is organized as a set of horizontal bands interrupted by a single vertical actor. At the bottom lies a dark, bristling strip of scrub; above it a broader belt of ochre and green fields; then the light, cool run of water or path leading to the bridge; and finally the pale sky occupying the upper third. These horizontal strata are set into motion by the central tree, whose upward thrust and slight lean energize the calm stacking of land and air. The bridge and distant spire double as smaller verticals, punctuating the horizon line so that the landscape reads like a musical measure: long, sustained notes of field and sky cut by upright beats of human structure.

Color Architecture: Warm Earth, Cool Air, and Electric Accents

Color carries the structural work. Matisse assigns the fields a warm spectrum—ochres, oranges, brick reds—broken by cooler slips of green that indicate growth and shadow. The sky is a pale, milky blue swirled with soft violets that keep the light from turning chalky. The tree’s foliage is a chorus of greens—from sap and emerald to blackened olive—sparked with unexpected streaks of crimson and violet that suggest the effect of sun on shadow rather than literal leaf color. The bridge and buildings are held to simple chords: a lavender shadow face against a creamy sun-struck plane, the spire a cooler, darker wedge that quietly anchors the left side. Because these hues are tuned to one another rather than to local description, the entire landscape feels coherent under one light.

Light, Weather, and the Toulouse Atmosphere

The painting’s light is high and clear, the kind that bleaches contrast at noon and makes warm tones hum. Instead of relying on deep cast shadows, Matisse lets temperature shift carry the sense of illumination. Ochres warm where the field faces the sun, and tilt toward violet where furrows fold away. The underside of the tree holds dark greens, yet the tops of its leaves flash with yellow-green notes. The sky, though pale, is not inert; thin strokes of violet and rose breathe through the blue so that the air feels mobile. The overall impression is late morning brightness with a faint breeze stirring the tree and rippling the water.

Brushwork and the Tactile Logic of Surface

The surface tells the story of making. In the foreground Matisse lays down quick, jagged strokes that read as scrub and the residual growth of a harvested field. Across the mid-ground he switches to broader, more horizontal strokes that flatten into ribbons of cultivated earth. The water or path is brushed in smoother, longer pulls, distinguishing its plane from the rougher field textures. In the tree he stacks short, flicked touches that climb the trunk and flare outward, creating a tufted silhouette. Finally, the sky receives the loosest treatment: blended patches and scumbles that keep the field open and light. Each zone has its own handwriting, allowing the eye to distinguish substance—earth, foliage, air—without relying on outline.

Drawing by Abutment: Edges as Meetings of Color

Look closely at the contour of the bridge arch or the tree’s crown and you will see that there is no hard line. The forms are drawn where one color meets another at the right value. The top of the bridge appears because a creamy light plane sits against a lavender shadow; the tree’s leaves register as mass where saturated greens press against the pale sky. This method—drawing by abutment—keeps the picture unified in a single light and allows Matisse to adjust depth and emphasis by the smallest shifts in temperature or value. A cooler green pulls the tree back; a warmer touch brings a branch forward. The result is a landscape that breathes.

Space and Depth Without Linear Diagram

Depth in this canvas is not mapped with measured vanishing points but built from stacked planes and calibrated color intervals. The near scrub is the darkest and most saturated; the ochre field beyond is lighter and smoother; the mid-ground around the bridge cools and thins; the far buildings become simple light-and-dark shapes; and the sky thins most of all, allowing the ground tone to warm it slightly. The eye walks into the picture by stepping across these bands. The vertical tree acts as a hinge, offering a stable reference that keeps the shallow depth from collapsing.

The Bridge as Motif and Link Between Zones

The Pont des Demoiselles itself is compact in scale yet crucial to the design. It links the human-built world to the flow of land and water without disrupting either. Its arch opening—indicated by a single dark sweep—allows the viewer to feel the passage beneath, and the upper line aligns with the horizon, tying architectural stability to the landscape’s own structure. By painting the bridge with lavender and rose rather than neutral gray, Matisse ensures it remains under the same atmospheric key as everything else.

The Tree as Protagonist and Color Catalyst

At the center stands the tall tree, the composition’s protagonist. It provides scale, breaks the horizon, and animates the field with its lean. More importantly, it acts as a color catalyst: saturated greens and violets condensed into a single vertical mass that throws the surrounding bands into sharper relief. The touches within its crown are not botanical details but color decisions—cool and warm greens stacked to suggest depth, quick red and violet notes to prevent dullness. Because the tree is so actively painted, it holds the eye even as the rest of the scene remains calm.

Rural Modernity and the Absence of Anecdote

There are no figures, no animals, no anecdotal embellishments. Matisse refuses picturesque stories. Yet the painting contains human presence in the steadiness of the bridge, the church spire marking a community, and the cultivated furrows that read as labor. By omitting narrative, Matisse allows the landscape’s own geometry—its bands and pivots, its color intervals—to carry meaning. The countryside outside Toulouse becomes modern not through subject but through structure.

Dialogue with Influences

The canvas converses with several contemporaries. From Cézanne, Matisse borrows the conviction that volumes and planes must be constructed with color strokes rather than filled inside drawn outlines; the fields are terraces of pigment rather than shaded patches. From the Neo-Impressionists he takes the lesson that adjacent touches can intensify each other, yet he declines mechanical divisionism; his strokes remain varied and responsive, tuned to substance rather than to a rule. One might hear an echo of Van Gogh in the charged greens and violets, but the temperament here is steadier, the intervals more measured. “Landscape of the Surroundings of Toulouse” is thus neither imitation nor repudiation; it is assimilation turned into a personal grammar.

Foreshadowing of Fauvism

Although painted years before the blazing chords of Collioure, the logic already points forward. Color is structural. Whites and pales are active. Shadows are chromatic, not gray. Edges arise from abutting hues. A few large shapes—the tree, the bridge band, the field, the sky—govern many small incidents. If one were simply to intensify the palette, pushing the greens toward viridian and the violets toward pure dioxazine, the painting would still hold because its scaffolding is strong. This is the groundwork that makes later audacity possible.

The Role of the Ground and Material Breath

A warm undertone peeks through thin passages, especially in the sky and along field edges. That undertone ties warm and cool chords together and prevents the blue from turning brittle. Matisse alternates thick impasto with thinner veils, letting literal light skim the ridges and sink into the scumbles. The painting’s physical skin echoes its subject: hard, tactile scrub where the land is rough; smoother pulls where water or path slides; and airy thinness where the sky expands.

Rhythm and Movement Across the Surface

Despite its stillness, the picture moves. The eye begins in the dark scrub, steps into the ochre field, crosses the cool band of water toward the bridge, rises with the central tree, and then drifts into the pale sky before falling back to the spire at left. This quiet circuit repeats, powered by the contrast between the vertical tree and the horizontal bands. The rhythm feels like walking along a canal or riverbank in heat, pausing to look through a bridge arch, then glancing up into the bright air.

How to Look Closely

Start at the tree’s crown and study how the greens interlock with small wedges of violet and crimson; notice how a single cool touch can push a branch back. Drop to the bridge and see how a lavender plane against a creamy plane creates architecture without outline. Follow the furrows in the field and feel how their strokes lay with the land, changing direction as the topography turns. Lift into the sky and find the pale rose and lilac scumbles that keep the blue alive. Step back until tree, bridge band, and fields resolve into three or four commanding shapes. Once you see those relations, every stroke begins to make sense.

Place Within Matisse’s 1898 Group

Alongside the sun-struck street scenes and bristling still lifes of the same year, this landscape shows Matisse testing whether his new chromatic grammar will hold across subjects. It does. The same principles that structure a façade against a blue sky—complementary harmonies, living whites, edges by contact—also build fields, a bridge, and air. The consistency across interiors, cityscapes, and landscapes in 1898 suggests that Matisse is no longer experimenting piecemeal; he is consolidating a way of seeing.

Conclusion

“Landscape of the Surroundings of Toulouse, the Pont des Demoiselles” is more than a countryside view; it is a declaration that color, touch, and a few large relations can render a place convincingly without resort to academic tricks. Warm earth bands balance a cool sky; a single, energetic tree binds the scene; a quiet bridge and far spire keep human presence within the harmony. The painting breathes because its parts listen to one another, each hue pitched to its neighbor, each stroke purposeful. From this clarity the later blaze of Fauvism becomes inevitable. What remains, even now, is the straightforward joy of looking: a strip of fields outside a city, a tree leaning in the light, and a bridge whose pale planes hold the day together.