Image source: artvee.com

Introduction to the Painting

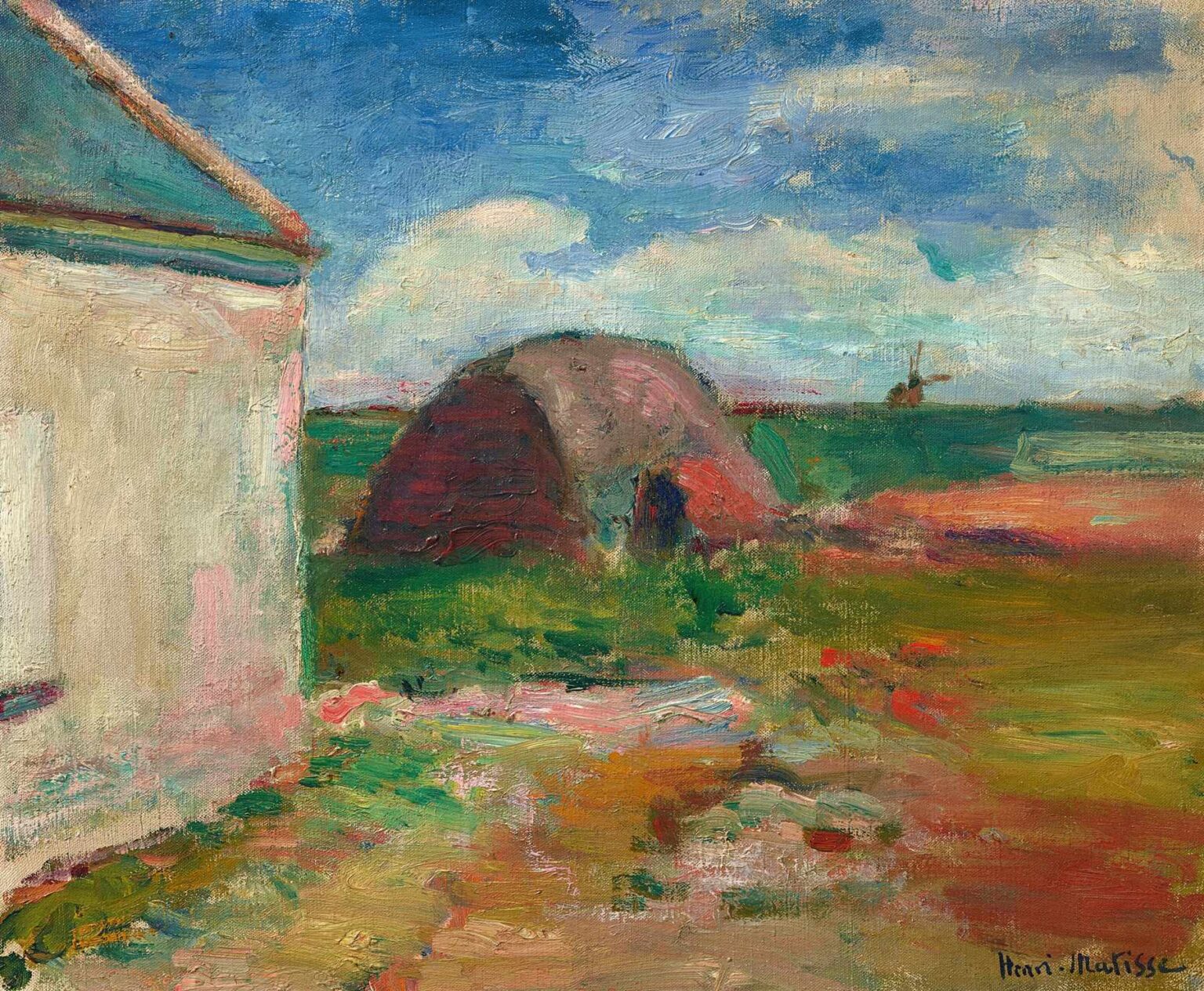

“Landscape of Brittany” captures a corner of the Breton countryside with a frankness that feels both observed and invented. A whitewashed building presses into the frame at left, its wall cropping the view and pushing our attention outward to a rounded haystack set against an expansive green field. Beyond it, a fine horizon line holds a tiny windmill and low bands of water or marsh; above, the sky is a restless weave of blues and warm grays. Nothing here strains for spectacle. Instead, Henri Matisse builds a modest scene out of color harmonies, thickened strokes, and the tactile presence of paint, announcing a young artist learning to make surface and sensation carry the weight of landscape.

Historical Context: Matisse in 1897

The year 1897 finds Matisse in his twenties, gathering influences and testing them against his own instincts. He had studied at the Académie Julian and in Gustave Moreau’s studio, where invention and personal vision were encouraged. Trips to Brittany exposed him to motifs favored by the Pont-Aven circle and to the lingering weather of Impressionism in the north. This was before the blazing breakthroughs of Fauvism, yet the seeds are present: a taste for constructive color, for simplification of forms, and for surfaces that confess the fact of paint. “Landscape of Brittany” is valuable not because it predicts everything to come, but because it shows Matisse consolidating what he needs—an eye tuned to light and a hand unafraid of the brush’s material.

Brittany as Motif and Mood

Brittany carried a double attraction for late nineteenth-century painters: its rural architecture and coastal horizons offered clear shapes, and its stormy light offered mutable atmospheres. Matisse taps both aspects. The white gable at left and the haystack at center are archetypes, stripped to simple volumes that read at once. The ground, streaked with damp color, and the battered sky capture a weather that changes even as you look. The tiny windmill near the horizon adds a human marker without dragging the painting into narrative. The region’s identity—work, wind, wide sky—arrives through a handful of signs.

Composition and Spatial Design

The composition is a study in asymmetry. Instead of centering the main structure, Matisse lets the house’s wall cut off the left edge, a decision that creates a thrust into the open field. The haystack—rounded, weighty, unmistakable—anchors the middle ground slightly right of center. A low horizon carries the eye across to the windmill, while the foreground spreads out as a scrim of ochres, reds, and greens, a kind of chromatic apron leading us into the scene. This architecture of large, readable masses allows the brushwork to remain lively without dissolving the picture’s order. The space moves backward in shallow terraces: wall and yard, stack and field, horizon and sky.

The Edge-of-Frame Building

The white building does more than set the locale. Its flat plane and cool tonality act as a measured foil to the chromatic turbulence elsewhere. The left edge’s abrupt crop suggests proximity—perhaps Matisse painted from the shelter of a wall or doorway—and invites the viewer to imagine the rest of the structure outside the frame. Subtle pinks and greens modulate the white, catching reflected color from ground and sky. As a geometric slab, the wall steadies the composition; as a painted surface, it proves that “white” is never simply white.

The Haystack as Pictorial Center

In a century when Monet had made haystacks famous as laboratories of light, Matisse approaches the motif differently. His stack is not a serial experiment in changing illumination but a stable, earthy mass. He rounds it with thick, curving strokes in maroons and bruised violets, then cools one flank with gray to turn the form. The stack’s arch echoes the curve of cloud bands; its earthy reds answer the ground’s warm notes. It is both object and color chord, a pivot around which the landscape’s relations turn.

Color Architecture and the Breton Key

The palette holds to a northern key: blue and slate in the sky, greens that toggle between sea-cool and inland moss, and ground colors warmed by iron-red, orange, and muddy yellow. Matisse builds harmony not by smoothing these hues into neutrality but by letting them meet cleanly. Cool sky pushes against the house’s warmer white; the green field recedes behind the haystack’s reds; tiny flicks of pink and turquoise dart through the ground like mineral veins. The overall effect is neither overcast nor sunny but luminous, a kind of wet clarity. Already one senses the painter’s habit of tuning a picture to a key and then playing variations inside it.

Light and Weather

Light is handled as atmosphere rather than as spotlight. The sky’s scumbled blues and grays are dragged with a dry brush so that the canvas texture participates, imitating clouds’ frazzle in windy air. Patches of white are left to glint as high cloud and as wet highlight on the ground. Shadows are never black; they are cooler mixtures of the local hue, especially under the stack and near the house. Everything suggests a day between weathers—sun trying the ground after rain, wind rising, distant showers across the flats. The painting feels timed to an interval rather than a dramatic instant.

Brushwork and the Living Surface

What gives the painting its pulse is the variety of its touch. In the sky Matisse drags and feathers, leaving bristle lines visible; in the field he trowels and dabs, creating a patchwork of strokes that behaves like turf and mud; on the house he lays flatter passages, then skims a veil of color so the white breathes. The haystack’s strokes follow its curvature like the grain on a carved form. No single technique dominates; the brush adapts to the sensation of each zone. Because the strokes remain legible, the viewer perceives not only a scene but the sequence of decisions that built it.

Drawing Without Outlining

The painting relies on painted edges rather than drawn contour. The corner of the wall is set by a firm value shift; the stack’s silhouette is carried by the meeting of green field and red mass; the horizon arrives where a darker band of land meets a lighter band of sky. Only occasionally does Matisse use a darker stroke to clinch an edge. This drawing-by-adjacency keeps the painting’s air intact and avoids trapping shapes under rigid lines.

Ground as Chromatic Tapestry

The foreground is a flexible carpet of color. Quickly mixed passages of ochre, warm pink, grass green, and iron red describe rutted earth without enumerating pebbles or blades. Wet-in-wet transitions and small ridges of impasto suggest recent rain and the drag of a boot. This area acts as an intake for the eye: we step into the color, then lift across it toward the stack and horizon. Because the foreground is so frankly a field of paint, it teaches us how to read the rest of the picture—less as illustration, more as a set of chromatic agreements.

Distance and Scale

Matisse signals distance with economy. The most saturated colors live in the near ground; farther back he cools and grays the mixtures. The horizon is an understated seam, and the windmill is a miniature constructed from two or three strokes—enough to declare scale without stealing attention. This staging keeps the painting readable from a distance and satisfying up close. The viewer senses open country and big sky without any need for linear perspective diagrams.

Influence and Independence

The canvas invites comparisons—to Monet’s serial haystacks, to the Pont-Aven taste for rural Breton motifs, to Van Gogh’s animated surfaces. Matisse borrows none of these habits wholesale. He avoids Monet’s vaporous envelope and instead sets distinct color planes into relation; he resists Pont-Aven’s cloisonné outlines and keeps edges breathable; he pares back Van Gogh’s directional fury in favor of measured strokes. The young painter accepts the challenge these elders posed—make color do more—and answers in his own plain syntax.

Materiality and Process

Because the paint is not over-fussed, the surface keeps its honesty. Knots of pigment catch light; thin scrapes reveal the ground; brush ridges cast tiny shadows that change as you move. You can sense the practicalities: a quick block-in of big zones, a return to articulate the stack, a re-stated sky, a final scattering of accents, including the windmill silhouette and the blushes on the house wall. That visibility of process is not a lapse in finish; it is a value. It keeps the picture in the present tense of its making.

The Human Trace Without Figures

There are no people in view, yet the scene bears human presence. The cut wall, the stacked hay, the windmill on the skyline—all signal labor and settlement. Their restraint permits the landscape to remain the protagonist. The absence of figures also aligns with the painting’s mood: alert, solitary looking. The viewer is placed as the one who has stepped from the lee of the house to survey the field before weather changes again.

Emotional Register

The painting’s feeling is steady and unpretentious. It holds warmth in the earth and cool in the sky without melodrama. The haystack’s reds introduce a quiet hearth at the center, a counterweight to the wind’s blue. The effect is of workday calm between tasks, a countryside that is neither idyllic nor bleak. Matisse’s sympathy is palpable, not because he sentimentalizes the subject, but because he lets color carry its true temperature.

From Observation to Construction

Perhaps the most important lesson of “Landscape of Brittany” is how Matisse moves from observation toward construction. He records what is there—wall, stack, field, horizon—but he builds the picture from relations: cool against warm, flat plane against rounded mass, still wall against moving sky. This constructive habit will later allow him to treat interiors and figures with the same clarity, composing with planes and chords rather than relying on descriptive detail. The Brittany canvas shows him discovering that a painting can be both faithful and designed.

Why This Early Work Matters

It would be easy to read this canvas only as a stepping stone to Fauvism. It is more than that. It is a complete, convincing landscape that teaches restraint and bravery in equal measure: restraint in palette and motif, bravery in the unblended stroke and the cropped composition. It reminds us that Matisse’s later serenity was learned, not inherited—that the capacity to make a room glow or a model rest within patterned light grew from these outdoor negotiations with weather, light, and ground.

Conclusion: A Weathered Harmony

“Landscape of Brittany” offers a weathered harmony made from a few essentials: a white wall, a red-brown stack, a green field, a low horizon, and a sky that holds its breath between showers. The painting’s pleasures come from watching these elements align—color against color, mass against sky—until the scene feels inevitable. In that inevitability we meet the young Matisse, already committed to the idea that painting should be clear, direct, and alive to the hand that makes it.