Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

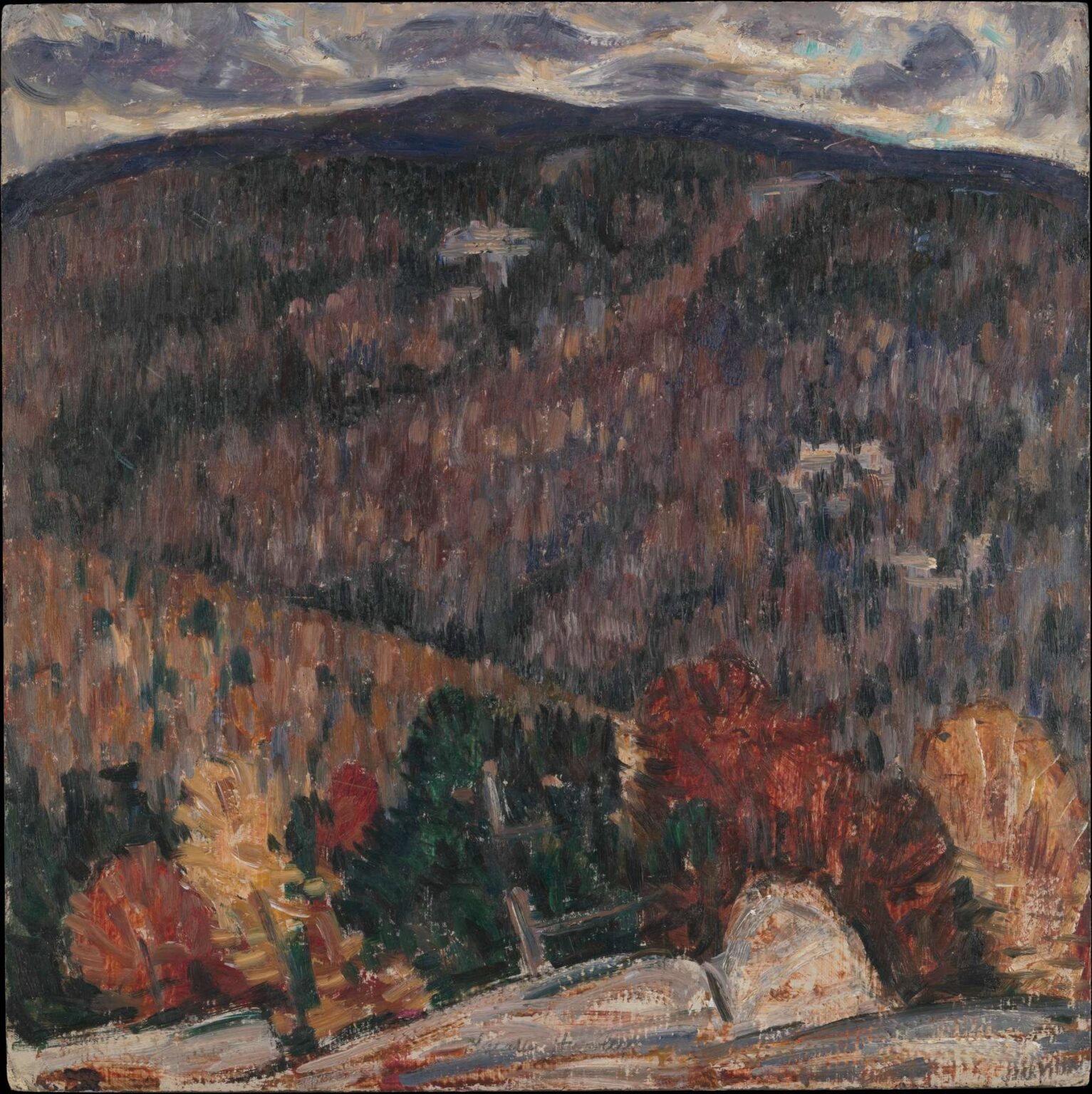

Marsden Hartley’s Landscape No. 25 (1909) occupies a pivotal place in the narrative of early American modernism, capturing the artist at a moment of profound transition. Painted shortly before Hartley’s departure for Europe, this canvas distills the rugged beauty and atmospheric intensity of New England’s terrain into a dynamic visual statement. At first glance, the work appears a straightforward autumnal view: a rocky ledge overlooking a densely forested valley leading to a distant ridge under a restless sky. Yet, beneath this surface lies an intricate interplay of compositional innovation, emotional resonance, and formal experimentation that prefigures Hartley’s later avante‑garde breakthroughs. Over the course of this extended analysis, we will explore Landscape No. 25 in exhaustive detail—examining its biographical context, its dialogue with artistic currents on both sides of the Atlantic, its structural and chromatic strategies, its layered symbolism, and its legacy within Hartley’s oeuvre and the broader sweep of American art.

Biographical and Historical Context

In 1909, Marsden Hartley was operating at the crossroads of multiple identities: a Maine native, an American painter rooted in academic training, and an emerging modernist eager to engage European avant‑garde ideas. Born in Lewiston, Maine in 1877, Hartley had spent his formative years traversing the landscapes of New England, absorbing the region’s seasonal extremes and natural grandeur. His early artistic education at the Cleveland School of Art and the Art Students League in New York instilled a facility with academic realism, while instructors like William Merritt Chase encouraged direct observation of nature and fluid brushwork. By the late 1900s, Tonalism—exemplified by artists such as George Inness and John Twachtman—was making inroads in America. Hartley’s landscapes from this period, including Landscape No. 25, reveal Tonalist influences in their emphasis on mood and subdued color harmony, yet they also betray an undercurrent of structural rigor that would soon propel him toward modernist abstraction.

Hartley’s impending European sojourn represented both an opportunity and a challenge. He would soon encounter Cubism, Fauvism, and the emergent Expressionist currents in Paris and Berlin—movements that shattered traditional pictorial conventions. Landscape No. 25, therefore, stands as one of the last purely American landscapes Hartley painted before his style underwent radical redefinition. It documents his final reflections on home soil, a pictorial love letter to a region that would continue to inform his art even as he embraced abstraction abroad.

Artistic Influences and Evolution

Hartley’s early work navigated the currents of American Tonalism and Impressionism. The subdued, atmospheric quality of Twachtman’s snow scenes and the poetic mysticism of Inness’s landscapes resonated with the young artist. Yet Hartley’s temperament and intellectual curiosity drew him toward more dramatic uses of form and color. Even in 1909, his brushwork in Landscape No. 25 exhibits a daring rhythmic energy—a departure from the gentle dissolutions of Tonalism.

On the cusp of his European period, Hartley had begun to sense the limitations of purely representational art. His travels overseas would expose him to the audacious color schemes of the Fauves, the fragmented geometry of Picasso and Braque, and the spiritual abstraction of Kandinsky and Franz Marc. While Landscape No. 25 does not yet display overt Cubist fragmentation, it does hint at an underlying geometric structure: the triangular sweep of the hills, the vertical thrust of tree strokes, and the rhythmic gradations of color that unify compositional zones. This latent geometry would blossom fully in his Berlin paintings of the 1910s, where he incorporated bold outlines and expressive faceting into allegorical portraits.

Formal Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Hartley arranges Landscape No. 25 into a tightly interwoven triadic structure. The foreground comprises a rocky outcrop, rendered in angular, horizontal strokes. Its shape anchors the viewer’s perspective and suggests a vantage point perched above the valley. The middle ground, dominated by a dense forest of autumnal hue, unfolds in a tapestry of vertical brush marks. These marks vary in length, width, and color, evoking the stand of deciduous and coniferous trees alike—maples, oaks, and pines in their seasonal attire. The distant ridge, spanning the upper third of the canvas, forms a gentle horizontal axis that counters the vertical thrust of the wood. Above, the sky—alive with roiling cloud formations and flickers of pale light—serves as a dramatic counterweight to the solid mass below.

Rather than employing a traditional receding perspective, Hartley flattens the pictorial space, allowing the eye to move laterally across planes of color and texture. The absence of a vanishing point imbues the scene with an almost abstract quality, emphasizing surface pattern and emotional tonality over illusionistic depth. Yet the layering of planes—from firmly defined foreground rock to soft, acre‑wide canopy to shadowed mountain—retains a sense of spatial hierarchy that grounds the composition in landscape tradition.

Chromatic Strategy and Seasonal Resonance

Color in Landscape No. 25 functions as both descriptive tool and expressive force. The palette pivots on complementary juxtapositions: warm russets and cool violets, olive greens and dusky browns, touches of golden ochre and slate blues. In the foreground, granite reveals undertones of pink and cream, while lichen and moss register as subtle flecks of chartreuse. The forest’s foliage unfurls in a complex mosaic: fiery reds of oak leaves, amber golds of birch, deep emerald of pine. Hartley masters the fall spectrum, avoiding garishness by tempering each hue with intermingled grays and earth tones.

The distant ridge, painted in cool blue‑violet, recedes under a veil of atmospheric perspective, reinforcing seasonal transition—autumn’s warmth yielding to winter’s approach. The sky, a brooding mix of lavender, pearl, and charcoal, captures the ephemeral drama of New England clouds. Hartley’s layering of thin glazes over thicker underpainting creates a luminous depth, as if sunlight flickers through the paint itself. This chromatic interplay not only conveys the look of an October landscape but also evokes the bittersweet mood of change, the tension between ephemerality and permanence.

Brushwork, Texture, and Surface Presence

Hartley’s surface treatment in Landscape No. 25 is a highlight of his early technique. The rocky ledge boasts robust impasto: dragged, scumbled strokes articulate the rock’s facets and roughness. In contrast, the forest’s vertical strokes—some barely brushing the canvas, others laden with pigment—establish a flickering, foliage‑like effect. Hartley varies his wrist movement—some strokes plumb straight down, others lean diagonally—to suggest the irregularities of the woodland trunk and branch network.

The sky is rendered in a freer manner: swirling, wind‑driven cloud shapes composed of loose, whip‑like strokes and thin washes. In zones where the canvas shows through, Hartley exploits the ground’s grayish tone to soften transitions. This interplay of heavy impasto and transparent passages generates a lively surface topology, reminding viewers that paint itself can mirror the tactile qualities of landscape—hard rock, layered leaves, ephemeral vapor. Moreover, the visible brushwork underscores Hartley’s hand in the composition, celebrating the paint’s material presence alongside its pictorial role.

Thematic Resonances: Nature, Transience, and Human Perception

At its core, Landscape No. 25 is a meditation on nature’s dual forces of constancy and change. The granite in the foreground conveys geological permanence forged over millennia. Yet the blazing deciduous leaves above evoke the fleeting, annual cycle of growth and decay. The tension between rock’s solidity and foliage’s fragility mirrors the human predicament: we stand firm against the currents of time even as we ourselves are subject to its flow.

Hartley, ever attuned to the metaphoric potential of landscape, invites reflection on human perception. The vantage point—looking downward over the valley—suggests contemplation, a vantage of both mastery and meditative distance. Yet the flattening of space reminds us that what we see is a constructed image, filtered through paint and brush. By foregrounding the act of painting, Hartley subtly acknowledges that our understanding of nature is mediated, shaped by our tools and sensibilities.

Dialogue with European Avant‑Garde

In retrospect, Landscape No. 25 reads as an anticipatory bridge between Hartley’s American roots and his impending immersion in European modernism. The vertical rhythms of the trees foreshadow the fractured planes of Cubism, while the abstract flattening and emphasis on surface pattern align with Der Blaue Reiter’s exploration of color and emotion. Yet Hartley never abandoned a deep respect for natural forms; his European contemporaries frequently rejected explicit references to nature in favor of pure abstraction. Hartley’s genius lay in his ability to synthesize these avant‑garde currents with a personal vision grounded in place. This painting thus becomes a prelude to the bold spiritual landscapes and symbolic portraits he would produce abroad, where the lessons of Impressionism and Expressionism would metamorphose into a distinctly American modernism.

Place Within Hartley’s Oeuvre

As one of Hartley’s final pre‑European landscapes, Landscape No. 25 occupies a crucial place in his chronology. The compositional clarity and emotive color palette anticipate works like Autumn Sea (1916) and Mount Katahdin (1939), while the painterly freedom points to the impassioned brushwork of his later abstract totems. Scholars often highlight this canvas as evidence that Hartley’s modernist trajectory was rooted not in a wholesale rejection of tradition but in an evolving engagement with it. By repeatedly returning to Maine’s natural wonders across decades, Hartley forged a unique continuity: a personal map of place and emotion rendered in ever‑shifting formal languages.

Influence on American Art and Contemporary Relevance

Hartley’s Maine landscapes of the early 20th century—among them Landscape No. 25—played a formative role in American modernism by demonstrating how local subject matter could seamlessly integrate modernist formal strategies. This synthesis influenced subsequent generations, from the Regionalists of the 1930s, who championed American life, to the Abstract Expressionists of the 1940s and ’50s, who prized gestural brushwork and emotional authenticity. Today, Landscape No. 25 resonates with viewers attuned to environmental change and the relationship between humans and their ecosystems. Its layered textures and vivid hues continue to inspire artists exploring the boundaries between representation and abstraction, nature and artifice.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley’s Landscape No. 25 (1909) is far more than an evocative autumn scene; it is a crucible in which academic training, regional affection, and nascent modernism coalesce. Through a masterful balance of compositional rigor, chromatic depth, tactile brushwork, and symbolic resonance, Hartley transforms a Maine vista into a universal meditation on permanence, transience, and the art of seeing. As both a document of place and a harbinger of the artist’s avant‑garde evolution, Landscape No. 25 remains a testament to Hartley’s inventive spirit and a cornerstone of early American modernist painting.