Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

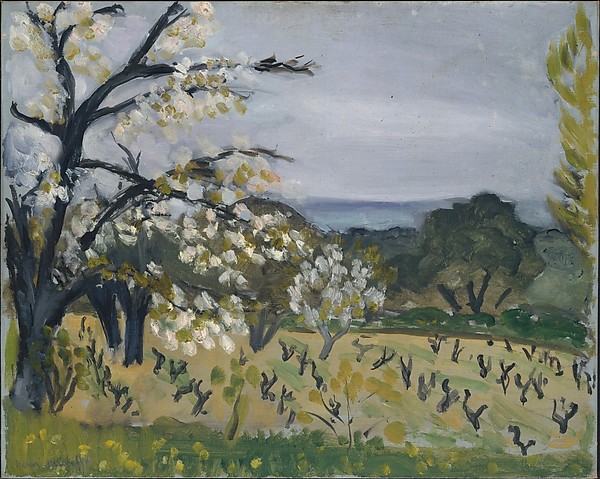

Henri Matisse’s “Landscape, Nice” (1919) condenses the sensations of coastal spring into an image that is at once simple and structurally refined. A low hillside undulates through the foreground, dotted with pruned vines; blossoming fruit trees—white, foamy, and wind-lifted—push in from the left; darker olive groves mass across the middle distance; and a pale, maritime sky settles over everything. The composition is spare, the brushwork frank, and the palette tuned to the soft greens, grays, and whites of early-season light. Rather than striving for panoramic spectacle, Matisse builds a compact, walkable world in which color, rhythm, and contour carry the meaning of place.

Historical Context: Matisse in Nice after the War

Painted in the first year of peace after World War I, “Landscape, Nice” belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, when he reoriented his art around interiors, gardens, and close-framed views of the Mediterranean environment. This turn was not escapist; it was a conscious effort to rebuild harmony through measured relations of color and shape. Where prewar Fauvism surfaced shock and saturation, the Nice pictures cultivate calm, clarity, and a human pace. In 1919 Matisse alternated between studio scenes—nudes on pink couches, women by windows, bouquets on striped tables—and fresh, lightly constructed landscapes. This canvas imports the same structural vocabulary outdoors: shallow, breathable space; large, legible color fields; and a touch of decorative rhythm that keeps nature in conversation with design.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance, three things stand out: the blossom-laden trees at left, the gridless scatter of vine stumps that stipple the field, and the low, layered horizon that yields a glimpse of sea-toned distance. These ingredients are archetypal for the Nice hinterland in spring: orchards in flower, pruned vines beginning their year, and the coast’s attenuated light under a sky that often feels more pearly than blue. Matisse treats each element with shorthand eloquence. The blossoms are thick touches of white and pale cream flicked with warm yellow; the vines are compact, calligraphic marks that tilt and vary; the distant groves are masses of olive green that read as volume without counting leaves. The scene registers as a morning’s walk rather than a cartographer’s account.

Composition: The Architecture of Gentle Diagonals

Compositionally, the canvas is a conversation between curving, recessive bands and vertical interruptions. A diagonal rise of ground enters from the lower right and sweeps toward the blooming trees; a second, softer bank mirrors it beyond, establishing a rhythmic, terraced movement. These green planes are checked by trunks that punctuate the left and far right edges and by a few stubborn verticals within the grove. The horizon sits high, compressing the distance and keeping the viewer close to the surface. Matisse further stabilizes the layout with a pale strip of sea-colored air that slides between the dark middle trees and the clouded sky—an understated, horizontal punctuation that prevents the scene from climbing out of the picture.

Palette and Temperature: Spring Keys in Green, Gray, and White

The palette is deliberately restrained. Foreground greens pivot between warm, yellowed notes for sun-struck slopes and cooler, blue-leaning greens in the dips; olives in the middle ground are darker and grayer, their tonality controlling recession without heavy modeling. The sky is a thin, cool gray with hints of violet and blue, a coastal atmosphere that allows whites to glow without glare. Blossoms are laid in with milky whites touched by straw yellow and blush pink, so they belong to the day’s climate rather than popping like confetti. Small passages of near-black—inside tree forks and along trunks—are used sparingly as internal armatures, not as outlines that lock the image into stiffness. Because each color family appears in more than one zone, the painting reads as a single chord rather than a set of isolated notes.

Light and Atmosphere: Maritime Softness

Matisse avoids theatrical sunlight in favor of the steady, marine light characteristic of Nice. There are few deep cast shadows; instead, temperature shifts do the work of turning forms. The blossoms are bright but never burned; the field holds a low sheen across its surface; the sky’s diluted pigment allows the canvas weave to breathe, giving the weather a living grain. This quiet climate aligns with the painter’s Nice-period ethos: light should make color legible and hospitable, not domineering.

Brushwork and Material Presence

The surface tells the story of its making. Blossoms are struck on with compact, creamy dabs that leave ridges; the field is brushed in broader, semi-dry passages that catch the ground and produce a grasslike tick without pedantry; tree masses are built from short, interlocking planes that carry volume by adjacency; trunks and branches are drawn wet-into-wet with calligraphic certainty, then occasionally feathered, so they breathe into the surrounding air. Nothing is polished away. The visible hand is integral to the picture’s freshness and to its truthfulness as a record of looking.

Space and Perspective: Shallow, Walkable Depth

Depth is modest by design. Overlap—vines before field, field before trees, trees before horizon—creates enough recession to inhabit, but linear perspective is suppressed. The height of the horizon compresses the view; the large left tree, cropped by the frame, pushes the foreground forward; and the far distance appears as a slim, cool band rather than an expansive gulf. This shallow construction is the landscape analogue to Matisse’s interiors: the painting remains a designed surface even as it hosts believable space.

The Blossoming Trees: Decorative Rhythm and Seasonal Time

The blooming trees carry more than botanical information; they supply rhythm and time. Their whites and creams are distributed in clusters that swell and taper, like phrases in music. A branch arcs up and out, blossoms collecting along its trajectory; another shoots horizontal, spattering petals in a lighter cadence. The effect is ornamental without ceasing to be natural. These trees tell us it is spring, a season of restart—an understated postwar resonance that would not be lost on a 1919 audience. By painting blossoms as pattern, Matisse turns seasonality into structure.

The Vineyard: Calligraphy of the Ground

Across the field, pruned vines appear as small, dark calligraphies—hooks, forks, bent Ys—each slightly different, none fussed into portraiture. They keep the green from becoming a passive plane and give the foreground a tactile rhythm underfoot. Their scale clarifies distance: largest and darkest near the viewer, they diminish and soften as they move back. Importantly, these marks are not a grid; their informal spacing prevents mechanical repetition and preserves the field’s organic sway.

Horizon and Distant Air: A Coastal Breath

Just above the darker middle trees glimmers a narrow, cool band that reads as sea or distant air. It is painted in a dilute mixture that thins to the canvas at points, letting the eye sense openness beyond the orchard. This horizon is neither a destination nor a narrative lure; it is a breath drawn between masses, a reminder that the garden sits within a larger coastal climate. That breath is vital to the painting’s calm: it releases pressure from the foreground’s detail and steadies the whole.

Drawing and Contour: Elastic Lines that Stabilize

Matisse’s lines are living instruments rather than fixed boundaries. He thickens a trunk edge where weight gathers, then lets it taper as the branch thins; he allows blossom masses to melt at their edges while snapping a darker accent into a fork for emphasis. The vines’ miniature strokes are quick and varied, asserting the human wrist amid the field’s larger sweeps. This elastic drawing prevents the landscape from hardening into diagram and keeps the viewer aware of the painter’s eye tracing relations in real time.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Path

The painting choreographs a clear loop for the gaze. Enter at the lower right along the rise of yellow-green, follow the scatter of vine marks as they tilt toward the left, ascend into the white blossoms, ride the main black branch outward, drift across the darker olive masses, inhale the cool horizon band, then return through the sky’s pearly lanes to the right-hand sliver of tree. Each circuit reconfirms the canvas’s measured pulse: push, pause, release; near, middle, far; warm, cool, warm again.

Comparisons within Matisse’s 1919 Landscapes

Compared with “The Promenade” from the same year, “Landscape, Nice” is more open laterally and more atmospheric vertically. “The Promenade” funnels the eye along a path toward a wall; “Landscape, Nice” spreads attention across blooming trees and a vineyard’s dotted ground. Both share the Nice palette, the shallow depth, and the reliance on temperature rather than cast shadow, but this canvas leans further into seasonal ornament—the blossom pattern—as a structural device. It is the outdoor counterpart to the interior still lifes and screen-framed portraits Matisse was painting in 1919: repeated motifs binding a space without choking it.

Dialogue with Tradition: From Corot to Cézanne, Recast

Matisse’s spring orchard acknowledges French landscape inheritance—Corot’s silvery airs, Cézanne’s built planes—while speaking in a modern tongue. The atmospheric sky and restrained values nod to Corot; the massed greens and planar foliage recall Cézanne’s constructive approach. Yet Matisse’s elastic contour, his decorative blossom rhythm, and his insistence on shallow, legible bands are distinctly his. He respects the scene’s truth while subordinating description to relation.

Symbolic Hints without Allegory

The postwar year and the choice of spring encourage symbolic readings: a field of pruned vines on the verge of fruiting, white blossoms announcing renewal, a quiet horizon promising room to breathe. Matisse does not press these into allegory; he keeps them as ambient meanings, inseparable from the way color and rhythm work. The picture’s optimism is structural—balance, clarity, a pulse that feels sustainable—rather than rhetorical.

Material Choices and Painterly Economy

“Landscape, Nice” exemplifies Matisse’s economy: just enough pigment thickness for blossoms to sit up, thin scumbles for sky and recessive greens, and a limited mix of earths, whites, blues, and blacks tuned to the day’s atmosphere. He resists glazing or over-modeling; he favors the honesty of first decisions that still read through. This restraint is not lack; it is the necessary discipline that makes the harmony audible.

How to Look: A Slow Walk through the Picture

The canvas rewards a methodical viewing. Stand close enough to feel the separate touches that build blossoms; back away until those touches cohere into cloudlike masses; then track the temperature shifts across the field, noting where yellow warms and blue cools the greens. Let your eye rest on the thin horizon band before returning to the near vines. This slow oscillation—micro to macro, touch to plane, part to whole—mirrors the act of walking through such a place and noticing it fully.

Lasting Significance

“Landscape, Nice” endures because it demonstrates how modest means can carry rich sensation. No bravura perspective, no dazzling chroma, no narrative hook—just a measured arrangement of spring elements tuned to a humane scale. In the context of 1919, that clarity was restorative; today it remains instructive. The painting shows that a landscape can be both a view of the world and a constructed order for the eye, a place where attention itself becomes a kind of renewal.