Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

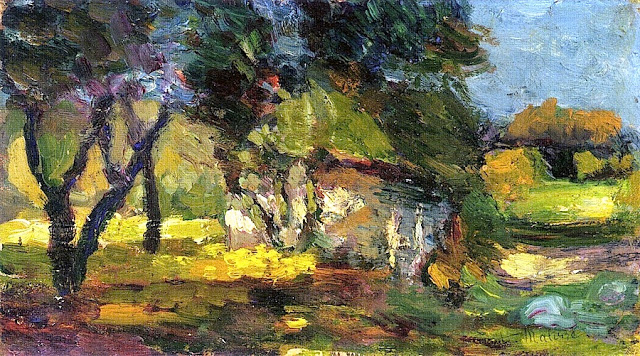

“Landscape, Corsica” compresses an outdoor experience into a handful of calibrated planes. The painting shows a low hut tucked under trees, a blaze of yellow meadow, a band of darker ground in shade, and a ribbon of sky. But these are not reported as separate things. Matisse fuses them into one climate by letting colors abut and mix on the surface. The hut’s pale stones absorb the heat of the field; the trees drink the blue from the sky; the ground reflects both. With every decision the artist favors relations over details, rendering a space you can stand in and an hour you can feel, while never letting you forget that the scene is made of strokes.

Historical Context

In 1898 Matisse’s palette shifted decisively under Mediterranean light. After Brittany’s darker, granitic motifs, Corsica offered higher key color, sharper shadows, and air that seemed to have its own tint. During this year he tested whether color could shoulder structural work previously handled by line and traditional modeling. “Landscape, Corsica” belongs to this experiment. Its limited size belies its ambition: to prove that a painting can read as place, weather, and rhythm by orchestrating warm and cool intervals across the surface. The clarity gained here will make possible the sudden blaze of Fauvism a few years later.

Motif and Vantage

Matisse chooses a low, intimate vantage, as if he has paused beside a tree to look across a bright field. Three slender trunks rise at the left edge, their dark legs rooted in a cool band of shaded ground. Just to the right sits a low-roofed hut or shed, its sun-struck stones nesting under a heavy canopy. Beyond, a thin path curves toward a distant hedge and a hill the color of ripe apricots. Patches of sky open between branches, cool and marine. The chosen viewpoint puts the viewer in the grove rather than outside it, forcing the eye to look through air and leaves instead of across a diagram.

Composition: A Weave of Bands and Nodes

The composition is a weave of horizontal fields punctuated by verticals and anchored by a central node. Horizontally, the image divides into shaded fore-ground, blazing mid-field, and airy distance. The vertical trunks on the left frame the scene, while the compact hut near center acts as a hinge that gathers light and redistributes it into surrounding foliage. At right, the curving path and bright meadow open the composition and guide the eye toward the horizon. Nothing is rigid. The canopy’s slanted mass leans over the hut, echoing the diagonal thrust of light across the field, so motion runs through the painting even as it remains balanced.

Color Architecture: Warm Earth, Resinous Green, and Mediterranean Blue

Color carries the entire structure. The sunlit field is pitched to a family of cadmium yellows and light ochres, brushing against warm greens so it feels hot without becoming raw. The canopy and tree masses are chromatic darks—bottle green, viridian, and blue-black—interrupted by small notes of violet and maroon that keep shadows alive. The hut’s stones are not neutral gray; they are assembled from creamy whites and warm tints that borrow from the field, so building and earth belong to one climate. The sky is limited to brief, potent patches of turquoise and cerulean. Because Matisse places these cools among hot neighbors, they read as deep air rather than as pigment on fabric.

Light and Weather

The hour is late morning or mid-afternoon, when light lies broad on fields and drops in mottled patches under trees. Matisse refuses theatrical, single-direction shadows. Instead, he lets temperature shifts carry exposure. Where the ground is open to the sky, yellows bloom; where leaves cast a net, greens deepen and cool. Highlights on the hut are creamy rather than white, convincing the eye that stone is reflecting sun, not glowing from within. The sky bleaches toward the horizon as strokes thin, mimicking the glare that softens edges in the distance. The total effect is of heat and mild wind: the grove hushes the air; the field hums with insects; the distance wavers.

Brushwork and Impasto

Every substance receives its own handwriting. In the field, short, buttered strokes stack like sheaves, their ridges catching literal light. The tree canopy is written in quick, interlocking dabs—some dragged, some stamped—that clump into weight. Trunks are pulled with longer, firmer strokes that thicken at the base and thin toward the fork, evoking sap and gravity without counting bark. The hut is built with compact, rectangular touches that suggest stone courses without drawing them. The sky is scumbled thinly to let the warm ground breathe through and keep the air luminous. The paint’s physical relief becomes part of the description: stones feel hard because strokes are squared; grass feels tufted because marks repeat with slight variation.

Drawing by Abutment

There is almost no contour line. Forms appear where planes of color meet at the right value. The left-hand trunks read because a cool, dense chord presses against a lighter meadow; the hut is “drawn” by warm tints against chromatic darks; the path’s edge emerges where a pale scrape rides beside a deeper green. This drawing by abutment keeps the whole scene in one light and allows Matisse to “adjust” form by warming or cooling a seam. It also matches natural vision: when you look into a grove, shapes are rarely bounded by ink-like lines; they meet and exchange light.

Space and Depth Without Linear Plot

Depth is achieved by stacked planes and calibrated saturations rather than rulered perspective. The shaded foreground advances through cooler, darker saturation and thicker paint. The sunlit band behind it leaps forward because of its warmth and value. The middle distance settles where color thins and edges loosen; the far hedge darkens to hold the horizon, and the sky’s cool patches recede by temperature alone. Overlaps—canopy crossing field, hut tucked under branches, path slicing behind shrubs—supply just enough cues to locate each element. The space is believable because the eye walks across temperature thresholds, the way it does in life.

The Hut as Pictorial Hinge

Though small, the hut is the composition’s engine. Its creamy stones carry the field’s warmth into the grove; its shadowed roof receives cools from the canopy. The object thus mediates between hot and cool, light and shade. Because its geometry is simplified to a few planes, it behaves as a node rather than an anecdote. The viewer’s gaze lands there, then disperses into the trees or out across the meadow, repeating the painting’s rhythm.

The Trees as Gesture and Structure

The left-hand trunks function both as framing and as gestures that launch the composition. Their leaning forms echo the slope of the canopy and imply breeze. Their deep chromatic darks stabilize the palette and keep the high-key yellows from floating. In the central mass, brief flashes of violet and burgundy puncture the greens, turning a generalized shadow into living foliage. The variation of stroke direction within the canopy—some diagonal, some vertical, some circular—acts like wind passing through a single body.

Ground and Path: Stage and Tempo

The ground is a stage that controls tempo. In the foreground the shaded band is laid with broader drags and cool glazes, slowing the eye. The sunlit middle accelerates with tight, staccato notes of yellow and sap green. At right, the path curves away in paler touches, its color cooling slightly, which invites a slower traverse into the distance. These changes in tempo guide attention without theatrics and keep the small canvas from feeling cramped.

Negative Space and The Windows of Air

Busts of blue sky puncture the canopy like windows of air. Matisse treats these openings with as much material conviction as leaves. They carry their own strokes and tints, not mere holes left unpainted. This decision aligns with how one actually looks in a grove: the eye continually jumps between opaque forms and brilliant gaps; both are positive events. By giving the gaps substance, the painter prevents the canopy from becoming a flat patch and instead turns it into a living lattice.

Materiality and the Warm Ground

A warm undertone—ochre leaning to red—glows through thin passages everywhere. It is visible beneath the sky, at the edges of the hut, and in the paler parts of the field. This ground ties the palette together and keeps cool notes from turning chalky. It also simulates the Mediterranean phenomenon of reflected warmth: even shadows seem to carry a little sun. Where Matisse wants solidity, as at the base of trunks or in the hut’s wall, he piles paint and lets ridges catch highlights. Where he wants breath, as in the sky and distant hedges, he scumbles thinly so canvas weave participates.

Dialogues with Influences

The canvas converses with several contemporaries without imitation. From Cézanne Matisse takes the belief that volumes are built from adjacent color patches; the hut and trees turn because planes meet at tuned intervals. From the Neo-Impressionists he borrows the energizing effect of juxtaposed strokes, though he refuses pointillist regularity; his marks lengthen, compress, or swirl according to substance. From Van Gogh comes the confidence that tree forms can be gestures and that chromatic darks—greens, violets, maroons—are livelier than bitumen. Yet Matisse’s temperament rules: the painting trusts equilibrium over drama, clarity over agitation.

Foreshadowing Fauvism

“Landscape, Corsica” already contains the grammar of Fauvism. Shadows are chromatic, not brown. Whites are inflected—creams, pearls, and lemon tints—rather than dead. Edges arise from color meetings, not outlines. A few large shapes organize the experience: shaded band, sunlit field, canopy mass, sky windows, and the hut as hinge. If one amplified the chroma—yellows to cadmium, greens toward viridian, blues into hotter cerulean—the picture would still hold because the scaffold is exact. This is why the later blaze of 1905 feels inevitable rather than abrupt.

The Emotional Temperature of the Scene

The mood is alert calm. Heat pulses in the middle band, but the shaded fore-ground moderates it, and the sky’s cools ventilate the canopy. The little hut offers shelter without sentimentality. There are no figures, yet human presence is implied by the structure and path. The painting honors the ordinariness of a working landscape while translating it into a lucid harmony of intervals. It is a space for a pause during a walk, a memory of standing in dappled shade while a field flickers.

How to Look Slowly

Begin at the left edge and feel the density of the trunks—their dark chords pressed against lighter meadow. Step into the shaded fore-ground; notice how cool strokes spread laterally, flattening the plane. Let your eye strike the hut, and watch how its creamy lights pick up from the field while its roof drinks from the greens above. Follow the canopy’s strokes outward to the right-hand path; note how colors cool and touch thins, releasing you toward the horizon. Finally, soften your focus until the painting resolves into interlocking bands—dark, bright, dark-laced-with-blue—and sense how few decisions are needed to persuade you of place and hour.

Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

Among the Corsican works of 1898, this canvas demonstrates that Matisse’s new grammar of color and planes could handle complex foliage as fluently as façades or interiors. The same principles that build a bedroom lamp or a Toulouse street build these trees and this hut: relations over details, chromatic darks over black, living whites over chalk, and edges born at seams. The picture thus occupies a crucial rung in the ladder leading to Collioure, to the blazing harbor scenes and interiors where pattern and color become sovereign.

Conclusion

“Landscape, Corsica” is a compact manifesto. A grove, a hut, a field, and a scrap of sky are enough for Matisse to show how painting can think: space through stacked planes, light through temperature shifts, substance through tailored brushwork, unity through a warm ground humming beneath all. The small stone building serves as a hinge, the path as invitation, the canopy as breathing ceiling, and the sky as relief. Nothing is over-explained; everything is tuned. In this quiet corner of Corsica, Matisse finds the equilibrium that will support his most daring color—proof that when relations are exact, the world can be rebuilt in paint and still feel inevitable.