Image source: wikiart.org

A Complete Analysis of “Landscape” by Henri Matisse

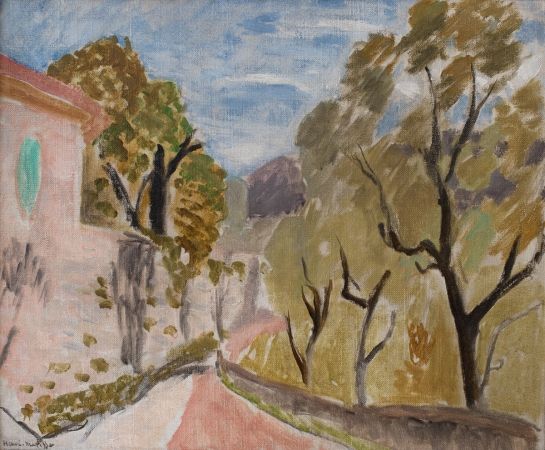

Henri Matisse’s “Landscape” captures a corner of the Midi with the kind of lucid simplicity that defined his turn to the South in 1918. A pink road winds between a garden wall and a row of loosely massed trees; a pale house with a mint-green window anchors the left edge; low mountains lift beyond a veil of leaf and air; and a high, lightly brushed sky stretches across the top of the canvas. Nothing here is fussy or ornamental, yet the view hums with rhythm. Matisse reduces the scene to a few decisive relations—curve against vertical, warm against cool, solid wall against breathing foliage—so the picture reads instantly and then deepens as you linger.

Historical Moment and Location

The painting belongs to the first season of Matisse’s Nice period, when he left the harsher northern light for the tempered clarity of the Mediterranean. In 1918 he was testing a new key: moderated color, shallow breathable space, and black used as a positive, organizing pigment. While later Nice canvases fill with interiors and patterned screens, this outdoor subject shows the same grammar applied to a hillside street in the south of France—the Midi that offered him not just sun, but steadiness.

What the Painting Shows

A winding road, the pink of warm clay, rises from the lower edge and disappears into foliage. To the left, the stucco flank of a house presses into the frame, its mint-green, almond-shaped window an eye that watches the street. A garden wall leans along the road, catching light on its top edge and shadow beneath. On the right, trees lift in airy clusters; some trunks stand bare like calligraphy, others are padded with olive-green crowns. Farther back, a mauve-violet mountain wedge peeks through the interval of trees, and above it a cloud-flecked blue carries the day’s mild breath.

Composition and Spatial Design

Matisse structures the painting around two diagonals: the road’s sweeping S-curve and the counter-slope of the stone wall. These lines establish a gentle, readable tempo, guiding the eye up and in before releasing it toward the mountain and sky. The left edge is stabilized by the cropped house, which supplies planar verticals and a necessary straight edge among the organic forms. The right half answers with a rhythm of uprights—trunks and branch forks set in dark, elastic strokes. Depth is achieved through overlap and value rather than linear perspective; as forms recede, their edges soften and temperatures cool, yet the space remains held close to the surface so the image reads as both view and design.

Palette and Mediterranean Light

The palette is a tempered Mediterranean chord. The road mixes coral pink with touches of raw sienna; the wall and distant slopes sit in warm grays and mauves; foliage ranges from olive and sage to lighter, silvery greens that suggest sunlight passing through leaf. The sky shifts from powder blue to milky white in soft, horizontal veils. Because saturation is moderated, temperature does the expressive work: cool greens breathe beside the road’s warmth; the mint-green window freshens the stucco’s peach; the violet mountain cools the middle distance and leads the eye into air. Light is not a spotlighted event; it is a set of tuned relationships that make the scene feel breathable.

Black as a Positive Color

In Matisse’s hands black is never a mere outline. Here it acts as a structural pigment: calligraphic strokes define trunks and branchlets; a few dark passes set the shadowed underside of the wall; slender accents weight the window and the road’s seam as it turns. Where black meets the sky it gleams with a slight halo; where it runs through greens it intensifies them. These notes supply the painting’s bass line, preventing the quiet palette from slackening and keeping the composition crisp.

Brushwork and Surface

The surface tells you how the view was found. The sky is laid with long, lateral strokes that leave soft ridges like the grain of wind. Leaves are built from short, angled touches that overlap like scales; the trunks are made with longer, elastic marks that thicken and taper, recording pressure and release. The road is brushed in broad, lightly varied bands that flow with the curve. Matisse resists cosmetic blending; instead, he lets strokes end visibly against one another so the picture retains the energy of its making even as it communicates calm.

Edges, Intervals, and Joins

Edges are tailored to the job. Where stucco meets sky the seam is clean, a logical boundary for architecture. Where foliage meets air, the join is breathed—scumbled transitions imply light slipping through leaf. The top of the wall is a bright, firm edge that carries a thin highlight along its length; under it, a soft shadow seam seats the plane in space. Equally important are the intervals: the gaps between trunks, the window of air between the tree masses and the mountain, and the strip of light road that flashes where it turns. These pockets of space keep the simplified forms from clumping and let the painting breathe.

Climate Rather Than Weather

Nothing here is staged for a meteorological effect—no raking sun, no imminent storm. The light is steady and humane. Shadows are cool but not blue; whites are milky, not blinding. Matisse’s aim is climate: a durable sense of day that could describe many days. That choice lends the work a feeling of lasting time rather than a notation of an instant. It also aligns with his broader pursuit of balance and serenity after the disruptions of the war years.

Rhythm and Movement Along the Road

The road does more than carry the eye; it sets the painting’s cadence. Its S-curve divides the rectangle into breathing compartments and prevents the planar composition from turning static. Notice how the inner edge of the curve tightens as it approaches the wall, then relaxes as it pulls away toward the foliage. The repetition of this tightening and release echoes in the tree silhouettes, in the way branch forks narrow and then open, and even in the sky’s soft, alternating bands. The whole scene moves gently, like walking.

Architecture and Nature in Dialogue

One pleasure of this canvas is the calm conversation between made and grown. The house is reduced to a few planes and a single, mint-green window; the wall is a long wedge with a bright top. These simple forms stabilize the right side’s vegetal rhythms. Their colors are related to the scene—stucco warmed by the road, window cooled by the sky—so the conversation stays harmonious rather than oppositional. The viewer senses a lived place, not an isolated view of trees.

Dialogues with Tradition

Matisse’s landscape quietly absorbs lessons from Cézanne—build the world from planes of color, keep forms constructive rather than feathery—while relaxing them into breath. The calligraphic darks and the cropping that lets trunks and house run out of frame recall Japanese prints. And the restrained chord of color, unlike the early Fauvist blaze, speaks to his Nice-period conviction that harmony can carry feeling more deeply than shock. Tradition here is a set of tools in service of clarity.

Comparisons within the Early Nice Constellation

Placed alongside “The Road,” “Landscape around Nice,” and “Landscape with Cypresses and Olive Trees,” this painting reads as their lighter, more domestic cousin. It shares the sweeping path of “The Road,” but with gentler contrast; it echoes the calligraphic trunks of “Landscape around Nice,” but opens more sky; and it balances architecture and foliage like “The Blue Villa,” though on a humbler scale. All depend on the same vocabulary: moderated color, living black, shallow depth, and forms simplified to essentials.

The Psychology of the Scene

Because there are no figures, mood arrives through the behavior of forms. The road’s curve invites without urgency; the mint-green window and the warm wall suggest habitation without gossip; the trees lean but do not menace; the mountain sits as a friendly anchor. The painting offers a quiet state of attention—the psychology of walking and noticing. In 1918 that kind of poise was more than decorative; it was restorative.

How to Look: A Guided Walk

Enter at the lower edge where the pink road swells. Follow its inner seam until it brushes the sunlit lip of the wall; pause on that bright edge, then ride the curve into the foliage where dark trunks rise like strokes of ink. Slip through the interval to the mauve mountain; let your gaze lift into the sky’s pale bands, feeling their faint horizontal pull. Drift left to the mint-green window and the stucco plane, read the small adjustments of tone that seat the house in air, then step back to the road’s widening mouth to run the loop again. The painting repays this slow circuit with a rhythm you can feel in your breath.

Material Evidence and Revision

Look closely and the canvas remembers its making. A road edge redrawn with a warmer pass, a tree crown widened and then trimmed with a veil of sky, a wall top cleaned with a narrow bright stroke, a soft halo where the house’s roofline was adjusted. Matisse lets these pentimenti remain, trusting them to carry the authority of searching rather than the sheen of finish. The calm we feel is earned.

Lessons for Painters and Designers

The canvas offers a compact primer in economy. Limit the palette and let temperature shifts do the lifting. Use black sparingly but decisively to organize space. Vary edge quality to seat forms in air. Give large shapes clear jobs—house as stabilizer, road as conductor, wall as hinge. Leave evidence of process so surfaces stay alive. The result is an image that reads quickly from afar and rewards close attention up close.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century on, the painting looks fresh because its clarity aligns with contemporary sensibilities. Big shapes register at a glance; the palette is sophisticated but quiet; the brushwork is visible and honest; the shallow space suits graphic and photographic habits of seeing. Most of all, it trusts a few exact relations—curve, vertical, warm-cool—to stand in for the complexity of place. That trust makes the picture durable.

Conclusion: Lasting Significance

“Landscape” demonstrates how little is needed to build a world that feels complete. A road, a wall, a house, a row of trees, a wedge of mountain, a clouded sky—organized with care and tuned by temperature—become more than topography. They become time, climate, and pace. The painting stands as a clear statement of Matisse’s early Nice vocabulary: serenity built from structure, intimacy achieved through restraint, feeling carried by color and line rather than by anecdote. It is a view you can live with—one that resets the breath and clarifies the eye.