Image source: wikiart.org

First Glance: A Landscape Built from Color and Air

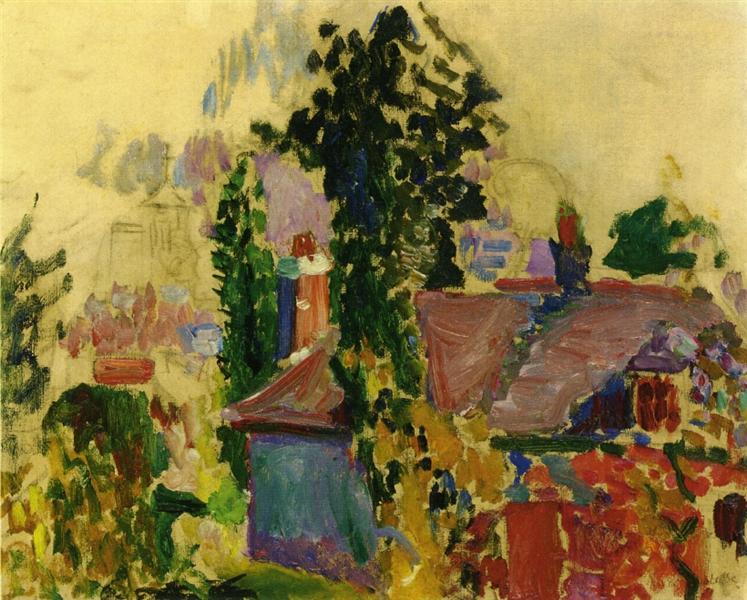

Henri Matisse’s “Landscape” of 1904 presents rooftops, chimneys, trees, and garden growth as an orchestra of bold chromatic notes suspended in luminous air. Much of the canvas remains an exposed warm ground, as if the very atmosphere of a Mediterranean afternoon had been poured over the scene before structures and foliage are coaxed out of it. Forms are indicated in stacked, vibrating patches—emerald greens, lilacs and mauves, cinnabar reds, and lapis blues—so that the image hovers between recognition and pure sensation. The subject is everyday architecture glimpsed through vegetation, yet the experience is anything but ordinary: the painting shows the moment when color stops merely describing the world and starts constructing it.

A Transitional Year and the Road to Fauvism

The year 1904 is pivotal for Matisse. He is absorbing lessons from Neo-Impressionism—optical mixtures, divided touches, and the primacy of light—while pushing beyond its systemization toward a freer, more intuitive color. “Landscape” sits precisely at this juncture. It retains the flickering energy of divided brushwork but refuses to be ruled by dot and grid. The painting anticipates the incandescent Fauvist canvases of 1905 by letting patches of saturated pigment carry structural weight; at the same time, it keeps a casual intimacy—a studio-terrace or hillside vantage—that anchors experimentation in lived observation. The work feels like research and revelation at once.

The Motif: Rooftops, Garden, and a Central Tree

Read the scene from the center out. A dark, columnar mass—likely a cypress or dense evergreen—rises against the pale ground, acting as a vertical axis. To either side, low roofs sweep across in mauves and violet-greys, with brick-red chimneys capped by teal or mint-green notes. Below, a tangle of garden foliage breaks into yellow-green flares and cherry-red blooms. To the far left, forms dissolve into a merest whisper of outlines, as though houses were still coalescing from light. The hierarchy is unusual: vegetation competes with architecture for primacy, and the tree’s silhouette becomes a keystone that holds the composition together. The motif is ordinary—houses and plants—but Matisse positions it so that color relationships become the true subject.

Composition as a Field of Energies

Rather than locking the eye into linear perspective, Matisse organizes the picture by stacked bands and interlocking color blocks. A broad, warm “sky” of unpainted ground presses down like atmospheric glare. Beneath it, the dark tree climbs, flanked by sloping roofs that arc in counter-movement. Compositional thrusts run diagonally from lower right to upper left, while short, vertical chimney strokes punctuate the rhythm like syncopated beats. Negative space is crucial: the untouched ground at upper left and top allows the painted clusters to breathe, giving the sense that light is the canvas’s default state and color is a deliberate incursion into it. The result is simultaneously open and anchored, a dynamic equilibrium.

The Palette: Complementaries in Conversation

“Landscape” is built on conversations between complementary colors. Reds and blue-greens spar around the chimneys; violets and yellow-greens trade warmth and coolness across the roofs and foliage; small cobalt accents pop against creamy ground. These pairings are not decorative flourishes—they establish depth and temperature. Where a roof turns toward light, mauve warms to rose; where foliage thickens, green is cooled with blue, then shocked with a lemonish yellow to simulate sun strike. Because so many passages sit directly on the warm ground, that ochre undertone unifies the palette, lending cohesion to disparate notes. The color is sensuous, yes, but disciplined; pleasure is structured.

Brushwork and the Material Body of the Picture

Close inspection reveals a mosaic of strokes, each carrying specific information. Short, comma-like touches build the foliage’s tremor; broad, scooped pulls lay in the roofs; quick dabs place a window or chimney cap; dry-brush scumbles veil earlier strokes without obliterating them. Edges are rarely drawn as lines; they appear as seams where two colors meet, a hallmark of Matisse’s mature practice. In several places, especially at left and along the top, charcoal or thinned underdrawing peeks through—evidence of mapping before the color’s arrival. The surface is alive with speed and revision, allowing the viewer to retrace the painter’s decisions as if reading a musical score.

The Poetics of the Unfinished

Perhaps the painting’s most striking feature is its deliberate incompletion. Large tracts of raw ground remain, forming a halo around the central tree and dissolving the horizon. This “non finito” is not neglect; it is a strategy. By stopping short of total coverage, Matisse stages a conversation between the world as seen and the world as painted. The unpainted ground acts as light itself, a reservoir of brightness that makes the chromatic islands vibrate. It also preserves the spontaneity of first notations—the moment when a roof plane or shrub mass is captured in a single, decisive chord. The viewer witnesses process as content, which is a thoroughly modern proposition.

Light Rendered as Color Pressure

There is no descriptive sky, only the press of brilliance. Matisse renders noon not by painting the sun but by letting the pale ground overwhelm, so that colors must fight for their place within it. Shadows are scarcely literal; rather, they show up as temperature shifts—violet sweetening to rose, green deepening toward blue. The luminous feel of a bright day, with glare bouncing off stucco and tiles, is achieved by contrast between saturated patches and the breathing room around them. It is a physics of perception: light is the constant; color is the variable.

Space Without Chains

Traditional depth is gentle here, and that is intentional. Rooftops overlap, and the tree breaks the picture plane like a screen. Distance is suggested by the cooling of color and the loosening of detail toward the upper left, where buildings blur into ghostly outlines. Yet the surface remains assertive, the paint reminding you of its presence. This oscillation—the eye toggling between a believable village and a flat pattern—is central to Matisse’s aim. He gives you both the pleasure of recognition and the freedom of abstraction, without insisting that you choose.

Dialogue with Cézanne, Gauguin, and Neo-Impressionism

Matisse’s structural stacking owes a debt to Cézanne’s systems of planes, yet the strokes here are freer, less architectonic. Gauguin’s example is present in the clarity of color shapes and the refusal of fussy detail, though Matisse resists heavy outlines; edges breathe. From the Neo-Impressionists he borrows the principle that light can be intensified by juxtaposed pure hues, but he declines their strict pointillist discipline. In “Landscape,” science becomes intuition. The canvas reads like a synthesis: Cézanne’s solidity, Gauguin’s chromatic audacity, and Signac’s optics fused into a language that is unmistakably Matisse.

The Role of the Tree: Axis, Screen, and Pulse

The dark green tree at center is more than botany. It is the painting’s hinge. As an axis, it divides the rooftop masses into echoing halves; as a screen, it delays access to the implied distance beyond; as a pulse, it supplies the deepest value, the basso continuo beneath treble notes of yellow and pink. Its jagged contour, built of jostling strokes, asserts the living irregularity that Matisse loved in natural forms. Without that vertical, the composition would scatter; with it, the color chords cohere.

Gesture, Memory, and the Speed of Looking

Even when Matisse works in front of the motif, he refuses slavish transcription. “Landscape” feels made in bursts, as a sequence of returns to the subject. You can sense areas laid in from memory—left-side architecture proposed and then left in outline—as if the painter wanted to honor the first look, the impression that was freshest and truest. The painting respects the speed of perception: our eyes do not register a town all at once; we glance, dwell on a roofline, forget a corner, return to a chimney. Matisse’s surface records this choreography of attention.

The Lyrical Ordinary

One measure of modernism is its ability to find lyricism in the ordinary. There is no theater here, no picturesque ruin. Yet by releasing color from routine descriptiveness and using it to build space, Matisse converts a modest cluster of houses into a site of visual music. The chimneys become red notes against a green stave; roofs swell like chords; a violet block converses with a lemon flare across a gap of untouched light. The painting is not an escape from reality but a heightened encounter with it, distilled to essentials.

Technical Observations and the Feel of the Ground

The warm, absorbent ground is central to the painting’s effect. It reads as light and as paper at once, creating the sensation that the color has been pasted, scumbled, and floated upon a bright sand. Where the paint is thin, ground warms the hue; where the paint is thick, small impastos catch light and assert the stroke’s body. Occasionally a stroke ends in a lifted ridge, a physical record of brush leaving surface. These traces underscore the immediacy of the act—evidence that the painting is not a polished artifact but an encounter.

How to Look: Two Distances, Two Rewards

Stand back and the picture resolves into a lucid arrangement: pale field, dark vertical tree, two arcing roofs, and flower-like outbursts below. The palette reads as a single chord—golden light keyed by greens and violets. Step close and the world breaks into tesserae: separate greens in the shrubbery, a dozen violets in the roof, a mint-green highlight asserting a metal cap, a quick maroon squiggle recording a window. The painting invites both readings and thrives on the oscillation between them.

What This Landscape Means for Matisse’s Trajectory

“Landscape” is a threshold canvas. It foreshadows the bolder, saturated planes of the following year while keeping the intimate scale and exploratory candor of a painter still testing his instruments. The work demonstrates that Matisse’s eventual Fauvist blaze is not a rupture but a refinement. He learns here that color can stand in for architecture, that unpainted space can be a source of brilliance, and that simplification—bold but precise—heightens sensation rather than narrowing it. The discovery is not theoretical; it is born, brushstroke by brushstroke, from looking at a real place in real light.

A Quiet, Lasting Radiance

What lingers after the analysis is the painting’s quiet radiance. The scene is half-whispered and half-sung, with forms offered and withheld. The unpainted regions glow like silence inside music; the colored passages answer with melody. By leaving so much to light and letting color do the heavy lifting, Matisse shows how a landscape becomes both a record of a place and a record of seeing. In 1904, standing on the brink of Fauvism, he finds in rooftops and leaves the means to construct an art of clarity, intensity, and poise.