Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

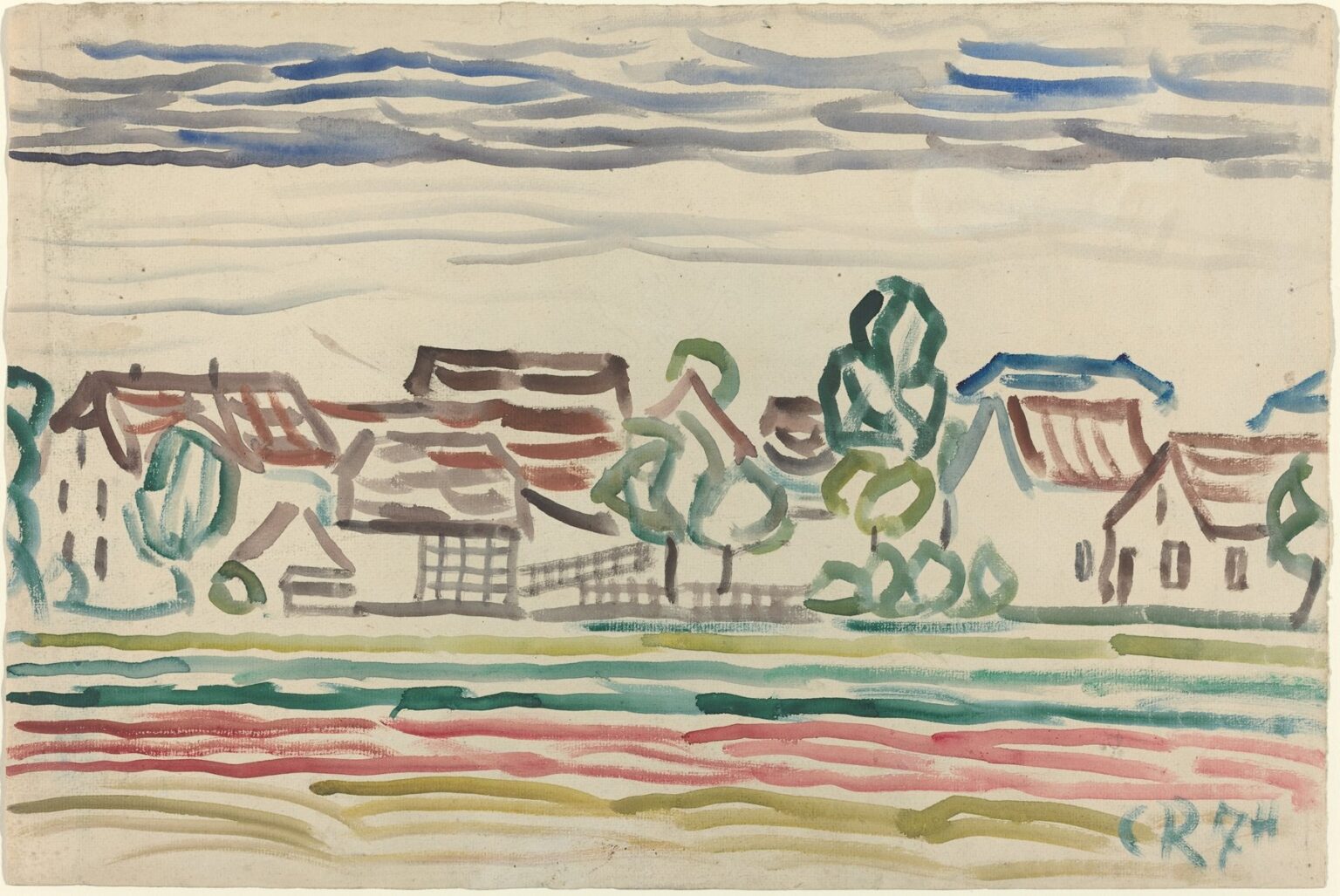

Christian Rohlfs’s “Landscape” from the 1870s offers a compelling glimpse into the formative years of an artist who would later become a leading figure in German Expressionism. At first glance, this modest watercolor appears a simple rural tableau: a cluster of gabled-roof houses, rounded trees, horizontal fields, and a banded sky. Yet beneath its apparent naiveté lies a sophisticated interplay of observation and invention. Rohlfs here experiments with flattening spatial depth, employing decorative color bands, and liberating brushwork—all gestures that prefigure the bold formal and emotional intensity of his later canvases. In this analysis, we will examine the socio-political currents of 1870s Germany, trace Rohlfs’s shift from academic Realism toward freer plein-air expression, and explore in detail how the painting’s composition, palette, technique, and underlying meanings converge to foreshadow the artist’s mature breakthroughs.

Historical Context

In the wake of German unification under Bismarck in 1871, the young German Empire embraced rapid industrial growth, urbanization, and a burgeoning middle class. Yet even as factories and railroads altered the national landscape, vast rural regions remained tied to centuries-old farming rhythms. For painters trained in the mid-nineteenth century—such as Rohlfs, who studied at the celebrated Düsseldorf Academy—the challenge lay in reconciling a lyric attachment to nature with the technical demands of academic figure and history painting. Across Europe, the Barbizon School in France had already pioneered a more direct approach to landscape, encouraging artists to work outdoors, capture transient light, and treat nature as a subject worthy in its own right. Rohlfs’s trips to Paris in the early 1870s exposed him to the soft atmospherics of Corot and the robust realism of Courbet. In “Landscape,” we see the imprint of that French influence, blended with a distinctly German sensibility that values structural harmony and the quiet dignity of village life.

Rohlfs’s Artistic Development

Christian Rohlfs entered the Düsseldorf Academy in 1868 at the age of nineteen. His early training emphasized meticulous draughtsmanship, chiaroscuro modeling, and the classical principles of composition. While Rohlfs mastered these academic techniques, he chafed under the Institute’s prescriptive ethos. A desire for greater spontaneity led him to experiment with watercolor and gouache around the mid-1870s. His first plein-air excursions into Mecklenburg’s pastoral environs revealed an appetite for rapid sketching, simplified form, and heightened color contrasts. “Landscape” belongs to this transitional period. Although the houses and trees retain enough realism to be legible, their outlines are sketched in a free, almost calligraphic manner. The fields become parallel stripes of pigment rather than meticulously rendered tillage. These innovations reflected Rohlfs’s growing conviction that paint could convey mood and atmosphere as much as precise topography.

Formal Composition

The structure of “Landscape” revolves around a tiered horizontal arrangement that organizes the scene with a graceful simplicity. The uppermost register presents a low horizon framed by a broad band of sky, defined by loose, undulating strokes of blue and gray. This sky does not imitate a particular meteorological moment but rather suggests the shifting atmosphere above a rural plainscape. In the painting’s middle zone, a continuous ribbon of village architecture unfolds. Each house is indicated by a bold yet tentative stroke—two sloping lines for a roof, a simple box for the wall. Between these built forms, Rohlfs inserts stylized trees: rounded canopies perched atop slender trunks, each rendered with a few swift dabs of green. The lower third of the sheet dissolves into wide horizontal washes of red, green, and ochre that evoke plowed fields or meadow strips. The absence of deep perspective or overlapping details lends the work a flattened, almost decorative quality. Yet within this apparent flatness, Rohlfs achieves a delicate balance: the weight of the sky counterpoints the patterned energy of the fields, while the village band holds the composition together, anchoring viewer attention.

Color Palette and Light

Despite its limited scale, “Landscape” reveals Rohlfs’s emerging command of color as expressive force. His palette draws from the natural world—earthy ochre, crisp sap green, village-roof red—but he applies these pigments with a fresh confidence that breaks from academic restraint. The sky’s cerulean and slate washes suggest distance in a cool tone that contrasts with the warmer hues below. The houses’ roofs, brushed in a muted brick red, pop against the cooler background, signaling human presence amid the landscape. Trees, indicated by varied shades of green, bring a note of vitality and natural rhythm. In the fields, alternating stripes of verdant green and faint red punctuate the foreground, creating a visual pulse that carries across the width of the paper. Light itself is woven into the painting through the paper’s off-white ground, which remains visible in unpainted areas. These untouched zones function like subtle highlights, suggesting sunlit earth or the reflective glimmer of a distant wall. By allowing the paper to show through, Rohlfs introduces a luminous tension between presence and absence, between paint and support, that would become a hallmark of his later Expressionist watercolors.

Brushwork and Technique

The painterly surfaces of “Landscape” combine fluid washes, dry-brush textures, and decisive linear accents. Rohlfs often loaded his brush generously, laying down broad swaths of color in one sweeping motion. In the sky and the fields, these wet-on-wet strokes bleed softly, creating gentle gradations that capture a sense of open air and rolling terrain. In the village band, by contrast, the pigment is more controlled and drier, allowing crisp edges to define rooftops and tree trunks. At times Rohlfs lifted or scumbled pigment with a nearly dry brush to produce irregular textures along the edges of roofs or the treetops, hinting at the roughness of textiles and bark. His linear marks—used to outline windows or suggest picket fencing—are applied with a dark gray or brown wash, uniting detail and abstraction in a single gesture. Through this blend of techniques, Rohlfs transforms a small sheet of paper into a dynamic field of incident: the eye travels from the smooth gradients of sky to the scratchy textures of field and the taut lines of architecture, each encounter enriched by the immediacy of the brush.

Symbolic Resonances

On its surface, “Landscape” depicts an unassuming rural scene. Yet in the context of post-unification Germany, the village held powerful symbolic weight. It represented rootedness in tradition, a bulwark against the disorienting thrust of industrialization and urban growth. Rohlfs’s decision to render the village in a decorative, almost stylized manner underscores its status as cultural emblem rather than mere backdrop. The horizontal stripes of fields can be read as a visual metaphor for agricultural cycles, the inexorable passage of seasons, and the continuity of human labor over centuries. Meanwhile, the banded sky suggests an overarching cosmic order, a reminder that natural forces shape human destiny. In this light, the painting resonates beyond its picturesque motifs, speaking to deeper yearnings for stability, harmony, and authentic connection in an age marked by rapid change.

Relation to Later Expressionist Works

Although “Landscape” predates Rohlfs’s most famous Expressionist paintings by several decades, the seeds of his mature vision are already present. His later works—characterized by thick oil impasto, jewel-like color contrasts, and abstracted, often biomorphic forms—extend the concerns first sketched here. In place of quiet houses and neatly striped fields, the mature Rohlfs conjures windswept trees erupting into cascading bursts of color or solitary figures rendered as rhythmic planes of pigment. Yet the earlier landscape’s flattened space, decorative banding, and emphasis on emotional resonance via color appear in nascent form. The continuity between the 1870s watercolor and works from the 1920s and 1930s confirms Rohlfs’s lifelong commitment to the expressive possibilities of color and gesture—even as he moved ever farther from representational conventions.

Conservation and Legacy

Preserving a delicate watercolor on paper from the 1870s demands careful environmental controls: stable humidity, minimal light exposure, and acid-free mounting. When well-conserved, works like “Landscape” retain their vibrancy and the subtle transparency that animates them. Over the past century, Rohlfs’s reputation has experienced fluctuations. Early critics often overlooked his late turning to abstraction, favoring his vigorous oil paintings of the Expressionist era. However, recent scholarship has redressed this imbalance by highlighting the artist’s more nuanced explorations of medium and mood. Today, “Landscape” is frequently exhibited in retrospective displays alongside sketches, spontaneous studies, and fully realized canvases, offering audiences a comprehensive view of Rohlfs’s journey. The painting’s renewed attention underscores its value as a critical link between nineteenth-century academic training and the avant-garde breakthroughs that reshaped European art.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s “Landscape” from the 1870s stands as a quietly revolutionary work. Although modest in scale and pleasing in its pastoral subject, the painting reveals an artist already probing the boundaries of representation. Through rhythmic horizontals, vibrant but controlled color, and a fluid amalgam of brush techniques, Rohlfs transforms a simple village scene into a canvas alive with emotional potential. The piece illuminates his early departure from academic orthodoxy, his absorption of French plein-air innovations, and the nascent formal experiments that would blossom into daring Expressionist statements in later decades. More than a charming sketch of rural Germany, “Landscape” functions as a pivotal moment in Rohlfs’s career—a testament to the artist’s enduring belief in the power of color, gesture, and decorative form to capture the spirit of an era and the essence of the human bond with nature.