Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

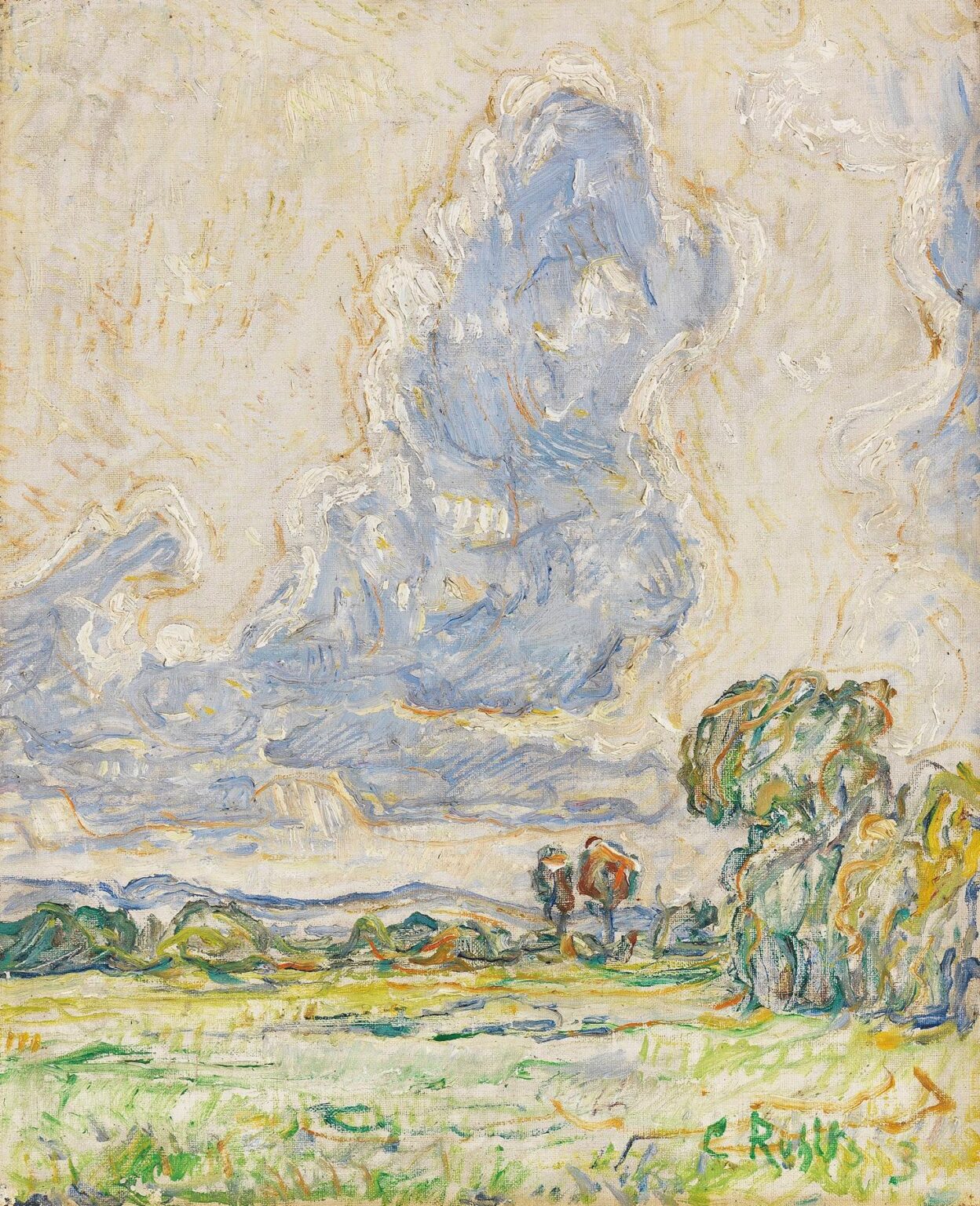

Christian Rohlfs’s Landscape (1903) represents a pivotal moment in the artist’s journey from Impressionist observation toward a more expressive articulation of nature’s inner life. At first glance, the painting offers what appears to be a quiet rural scene—a meadow stretching toward distant hills, punctuated by a cluster of windswept trees and surmounted by a luminous sky. Yet beneath this apparent simplicity lies a sophisticated interplay of gesture, color, and texture that transcends mere depiction. Rohlfs employs bold, swirling strokes to evoke the landscape’s vitality, allowing each brush mark to resonate with emotional intensity. Rather than merely recording what he sees, the artist translates his sensory and psychological response to the environment into a visual language of movement and atmosphere. Landscape thus becomes both a window onto a specific place and a mirror reflecting the artist’s evolving vision.

Historical Context

The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed seismic shifts across European art. Impressionism’s breakthroughs in capturing light and fleeting atmospheric effects had already challenged academic modes of representation. Simultaneously, Symbolist artists were probing the transcendent and psychological dimensions of imagery. In Germany, these currents converged as painters sought to balance fidelity to nature with an inner expressive impulse. Christian Rohlfs, born in 1849, had spent decades absorbing the traditions of realism and plein-air painting before gradually embracing freer handling of paint and heightened chromatic contrasts. By 1903, when Landscape was executed, Rohlfs had internalized lessons from Monet and Pissarro yet was also cultivating a distinct approach that prioritized brushstroke as a bearer of feeling. The painting thus stands at a crossroads: it retains the recognizable forms of land and sky while signaling Rohlfs’s emerging leanings toward Expressionism, which would fully blossom in the following decade.

Christian Rohlfs’s Artistic Evolution

Rohlfs’s progression from meticulous naturalism to dynamic expressiveness unfolded over several decades. His early works, guided by academic training in Düsseldorf and Karlsruhe, reveal careful attention to detail and a subdued palette. Travel in France during the 1880s introduced him to Impressionist innovations—broken color, rapid plein-air studies, and an emphasis on ambient light. Over the 1890s, he began experimenting with pastel and oil to capture more immediate impressions, loosening form and amplifying hue. Landscape reflects this period of transition. While Rohlfs maintains compositional coherence and a sense of place, his brushwork becomes more assertive, his color choices more vibrant. Forms dissolve into rhythmic patterns of paint, and the boundary between figure and ground grows porous. In this way, the work embodies a halfway point between Rohlfs’s earlier observational canvases and the fully expressive, semi-abstract visions he would produce after 1908.

Composition and Spatial Structure

At the heart of Landscape lies a thoughtfully orchestrated spatial scheme. The composition is divided into three horizontal zones: a foreground of textured meadow, a middle ground featuring gently undulating fields and a small stand of trees, and a broad sky dominating the upper half. Unlike strict perspectival constructions, Rohlfs relies on overlapping planes and gradations of color to suggest depth. The foreground grasses are rendered in warm greens and yellows, their strokes directed toward the viewer, creating an invitational thrust. Beyond them, the midsection’s darker, more consolidated hues form a visual belt that anchors the composition. The sky, by contrast, is an expansive canvas of swirling blues and soft whites, its brush marks spiraling outward. This layered arrangement leads the eye first across the terrain and then upward into the heavens, evoking a gentle journey from earth to sky that mirrors the human impulse to seek both grounding and transcendence.

Brushwork and Texture

Brushstroke is the defining element of Landscape, and Rohlfs treats each mark as a unit of expressive power. In the meadow, he employs short, choppy strokes that convey the restless energy of grasses stirred by a breeze. These dabs of pigment overlap and interweave, creating a tactile surface that almost invites touch. The trees in the middle ground are suggested through broader, more gestural sweeps, their foliage articulated with interlocking arcs of dark green, brown, and russet. The sky receives the most daring treatment: swirling vortices of pale blue and white, applied in thick impasto, generate a sculptural relief on the canvas. These spiraling forms convey the unseen currents of air and light, making the atmosphere itself a central protagonist. By varying stroke length, direction, and pressure, Rohlfs transforms the landscape into a living organism, its textures and rhythms made visible through paint.

Color Palette and Light

Color in Landscape does double duty: it delineates form while imbuing the scene with emotional resonance. The foreground’s warm ochres and chartreuse greens suggest sunlit grasses, hinting at midday or early afternoon light. In the middle ground, deeper olive and sienna tones evoke shaded earth and the muted density of tree trunks. Above, the sky’s luminous blues shift from cerulean to pale turquoise, punctuated by cloud forms touched with creamy white and faint gold. These highlights suggest altocumulus formations catching sunlit edges. Rather than a flat chromatic field, the interplay of warm and cool zones animates the canvas, creating dynamic tension. Warm tones seem to advance, closing the distance, while cool blues recede, conveying openness. This interplay of hue and temperature anchors the viewer’s perception and underscores Rohlfs’s sensitivity to the subtle choreography of light across land and sky.

Depiction of Nature and Form

Though Landscape depicts a specific natural setting, Rohlfs resists literalism. Instead, he distills the essence of meadow, tree, and sky into gestural shorthand. Individual leaves and blades of grass are subsumed into collective rhythms of stroke. The solitary stand of trees is rendered without botanical precision; trunk and canopy merge into sweeping forms that suggest both solidity and movement. Rohlfs’s technique aligns with the notion that nature is not merely a static tableau but an ever-shifting convergence of forces. The painting thus captures not just the visual facts of a scene but its atmospheric soul. In doing so, Rohlfs positions himself among artists who sought to go beyond mere imitation, believing that true understanding of nature arises from interactive perception—an exchange between environment and observer mediated through the act of painting.

Symbolism and Emotional Resonance

While Landscape can be appreciated for its formal qualities, its deeper impact lies in its symbolic and emotional suggestions. The swirling sky may be read as a metaphor for the mind’s own turbulence or for the unseen energies that animate the world. The steadfast trees, bending slightly but holding their ground, could symbolize resilience amid change. The pathway of light and color from foreground to sky evokes a spiritual ascent, reminiscent of Romantic notions of the sublime found in nature. In this sense, the painting transcends its geographical reference to become an allegory: nature as a mirror of human experience, where light and shadow, motion and stillness, birth a continuous interplay of hope and contemplation. Rohlfs invites viewers to inhabit this metaphorical space, where landscape and psyche converge.

Technical and Material Considerations

Executed in oil on canvas, Landscape demonstrates Rohlfs’s command of material. He builds texture through varying paint consistency—thicker impasto in the sky, more diluted passages in the distant horizon where the canvas weave shows through. At times he scores into wet paint, introducing fine linear accents that enhance directional flow. The underlying primed surface, likely a warm-toned ground, peeks through in areas of light application, lending a unifying warmth to the composition. Rohlfs’s palette knife occasionally augments brushwork, adding ridges and broken edges that catch ambient light differently. This emphasis on paint’s physicality reinforces the painting’s thematic focus on palpable atmosphere. In Landscape, the viewer is reminded not only of what the eye beholds but of how paint itself can evoke the very sensations of wind, light, and texture.

Relation to Contemporary Movements

Though Christian Rohlfs would later be associated with German Expressionism, Landscape predates the movement’s full emergence and occupies a liminal space between Impressionism and proto-Expressionist explorations. The emphasis on broken color and plein-air observation aligns with Impressionist practices, yet Rohlfs’s more robust impasto and emotive brushwork point toward a desire for inner expression. His swirling skies recall Van Gogh’s atmospheric dynamism, while his structural coherence nods to the disciplined foundations of German landscape tradition. In this way, Landscape exemplifies the transitional quality of art in the early 1900s—a period in which artists sought new visual vocabularies to articulate both the external world and the intensifying inner life. Rohlfs stands as a bridge figure, integrating naturalist observation with expressive potential.

Reception and Legacy

When first exhibited, Landscape drew admiration for its vivacity and painterly confidence. Contemporary critics noted Rohlfs’s ability to unify composition and emotion, praising the work’s ability to conjure the “breath of the breeze” and the “glow of sunlit grass.” Some traditionalists, however, were unsettled by the pronounced surface texture and the abstraction of detail. Over time, art historians have come to regard Landscape as emblematic of Rohlfs’s transitional phase—a key link between his Impressionist-influenced past and his later fully Expressionist works. Today, the painting is valued not only for its aesthetic qualities but also for the way it illuminates broader developments in early modernist painting. Its lively brushwork and atmospheric depth continue to inspire artists exploring the interplay of nature, emotion, and materiality.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s Landscape (1903) remains a masterful exploration of how paint can evoke both the tangible and intangible qualities of nature. Through a harmonious composition, dynamic brushwork, and a finely calibrated palette, Rohlfs transforms a simple rural scene into a vibrant meditation on light, movement, and emotional depth. The work captures a moment of artistic transition, reflecting the artist’s journey from careful observation to expressive articulation. In Landscape, one finds a space where meadow and sky, earth and spirit, converge in a continuous dialogue. Rohlfs invites viewers to step into this dialogue, to feel the sway of grass underfoot and to breathe the wind in the painted air, discovering in both the scene and themselves a shared vitality.