Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

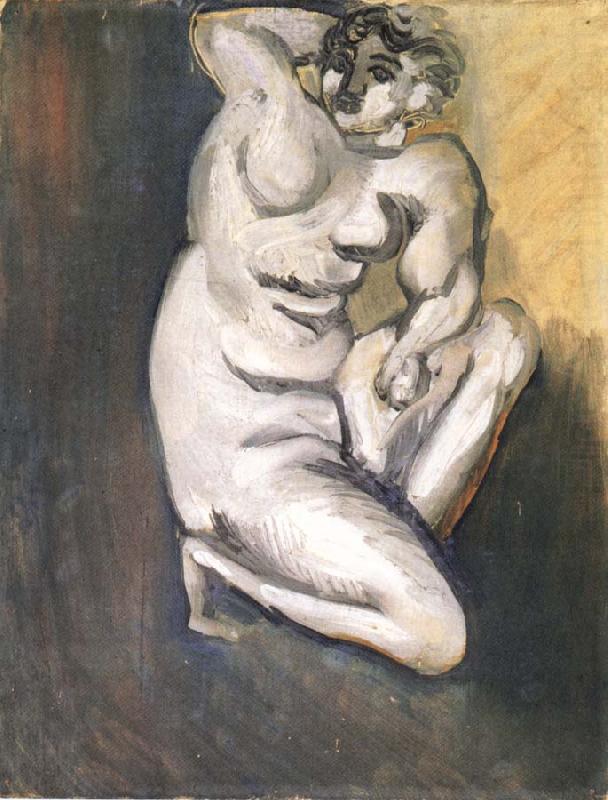

Henri Matisse’s “Kneeling Nude” (1919) is a compact drama of light and mass. A single figure, turned in three-quarter view and compressed inside a narrow field, seems to be carved out of paint. The body kneels and twists, one arm arched behind the head and the other drawing inward at the torso. Thick, chalky highlights race across the form; deep, inky shadows tuck beneath ribs, thigh, and jaw; and a cool, stormy background yields to a wedge of warm light at the upper right. The effect is sculptural and immediate. Rather than the upholstered interiors and leisurely odalisques that characterize much of Matisse’s Nice period, this study insists on weight, structure, and the urgent act of modeling a body with a brush.

Historical Context

The year 1919 sits at the threshold of Matisse’s postwar transformation. Europe had just emerged from the First World War, and artists across France sought a steadier visual language after the convulsions of the previous decade. Matisse, newly installed in southern studios, would soon be known for interiors, screens, and seaside light. Yet “Kneeling Nude” reveals another strand of his thinking: a return to the fundamentals of volume and contour, a desire to test how far painting could go toward the plastic immediacy of sculpture. Matisse had worked seriously as a sculptor since the first years of the century, and the monumental “Back” series occupied him intermittently from 1908 forward. In 1919 he was still digesting those lessons. This canvas records that sculptural attention at full intensity.

Subject, Pose, and Gesture

The figure is neither languorous nor passive. Kneeling on the left leg with the right drawn up, the model coils into a compact spiral. The torso turns; the pelvis counters; the shoulders torque in the opposite direction. One arm bends behind the head, opening an arc that exposes the chest; the other braces against the thigh, a point of tension that anchors the twist. The pose creates a modern contrapposto, condensed and athletic. Because Matisse crops the outer edges of the body near the canvas borders, the viewer feels physically close, as if standing just inside the studio’s circle of lamplight. The gesture is not a theatrical display but a test of balance, breath, and strength.

Composition and Diagonal Architecture

The composition is organized along a powerful diagonal that runs from the light at upper right down through the torso to the lower left knee. The figure occupies most of the rectangle, tilting like a piece of statuary against a wall. Negative space is used sparingly. A dark, vertical band at left provides a counterweight to the warm illumination at right, while a dusky wedge below the body lifts it forward. This diagonal architecture gives the picture its dynamism. The eye follows the shoulder’s arc to the ribs, drops along the hip, and returns via the forearm to the face, completing a loop that is both visual and kinesthetic.

Tonal Design and the Palette of Stone

Color is deliberately restrained. The body is cast in whites and gray-violets; shadows range from slate to charcoal; warm ochres glow along the right edge and in a faint halo at the shoulder. The palette evokes plaster, marble, or alabaster more than flesh. This is not an attempt to naturalize the skin but to present the body as a sculptural presence caught in a cone of light. The limited color range sharpens value contrasts, so that small changes in tone become expressive events: a cooler gray turning over the knee, a warmer light catching the breastbone, a deep black slicing beneath the jaw. The harmony is austere and purposeful.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Although the values recall stone, the surface is emphatically painted. Matisse lays in broad, assertive strokes that follow the form rather than negate it. Across the chest, the brush turns with the rib cage; along the thigh it pulls with the length of the muscle; around the knee it tightens into short, chiseling marks. The highlights are often dragged wet-in-wet across darker ground, leaving a broken edge that reads like carved facets. This handling communicates the tempo of work: fast where conviction is firm, slower where the form is negotiated. The canvas breathes with decision and revision, making the body feel discovered rather than diagrammed.

Contour as Armature

Matisse’s contour, a signature in all periods, is here weightier and more emphatic than in his decorative interiors. The line swells and thins like a sculptor’s tool scraping edges. Around shoulder, flank, and calf, a dark calligraphic stroke cinches the light planes into coherence. In other passages, the contour opens and is carried by adjoining tones—the cheek blends into the background, the upper arm softens at its edge. This alternation between declared line and fused edge lets the figure pulse between solidity and atmosphere, as if the body could step forward from the field or melt back into it at will.

Light as Sculptor

Light in this painting behaves like a hand. It arrives from the right, raking across the figure to carve planes. The brightest notes catch on clavicle, breast, abdomen, and shin; the deepest shadows pool under the rib cage, at the inner elbow, and behind the bent knee. Importantly, the light is not merely descriptive. It builds form. You can follow it across a single surface and feel the transition from convex to concave, from support to release. The modeling is not achieved by academic cross-hatching but by broad planes meeting decisively, a method that owes much to Cézanne’s construction and to Matisse’s own sculptural practice.

Space, Background, and the Theater of the Studio

The background is a shallow theater rather than an illusionistic chamber. A vertical band of dark umber and blue at left grades to a warm ochre glow at right, with a soft, neutral field between. This gradient asserts the direction of light and gives the figure a pocket of air without opening deep recession. The body reads as a relief mounted against a wall. That staging intensifies contact between figure and ground: the curve of shoulder presses against the warm wedge; the shadowed thigh pushes into the cool flank of the field. Space is felt as pressure and release, not as measured depth.

A Sculptor’s Mind in Oil

“Kneeling Nude” makes plain how thoroughly Matisse thought as a sculptor even when working on canvas. The figure is summarized into major masses—head, thorax, pelvis, thigh—each tilted in relation to the others. Transitions are planar rather than anatomical; muscles are implied by shifts of light rather than named tendons and fibers. The whole reads like a maquette rapidly modeled in clay and then “cast” in paint. This sculptural thinking links the painting to the “Back” reliefs and to Matisse’s broader exploration of torsion and compression in the human figure. It is a study not just of a pose but of how a body claims space by twisting through it.

Dialogue with the Classical and the Modern

The kneeling twist recalls antique torsos and Michelangelo’s ignudi, yet the handling is resolutely modern. Classical sculpture idealizes surface to marble smoothness; Matisse keeps the facture visible, refusing finish in favor of vitality. The contrapposto rhythm belongs to an old vocabulary, but its compression into a tight frame feels contemporary. There is also an echo of Rodin in the frankness of mass and the willingness to let form emerge from roughly hewn planes. At the same time, the flattened space and decisive edge-work align the canvas with modernist thought about the picture plane.

Body, Strength, and Dignity

Despite the narrow palette and the forceful lighting, the figure retains warmth and personhood. The face—half in shadow, half turning toward light—suggests alertness; the hands are compact and capable; the knees anchor the weight securely. This is not a decorative odalisque but a body in action, even at rest. The pose compresses the torso, creating rhythms across abdomen and flank that read as strength rather than fragility. Matisse’s respect is evident in the economy of detail and the seriousness of the modeling. The nude is neither eroticized nor anonymized; it is treated as a human architecture worth understanding.

Abstraction at the Edge of Observation

Stand back from the canvas and the body reads convincingly; step closer and the form dissolves into abstract relations of tone and edge. The inner elbow becomes a knot of lights and darks; the breast resolves into two adjacent planes; the knee into a clenched crescent of highlights. This elastic legibility is a hallmark of Matisse at his best. He refuses to choose between description and abstraction; instead he lets them oscillate. The eye enjoys both the recognition of a kneeling model and the pure design of lights and darks locked in a powerful spiral.

The Psychology of the Twist

Beyond formal concerns, the pose carries psychological charge. A kneeling body with one arm lifted behind the head exposes the torso with courage while simultaneously protecting it with the inward-drawn other arm. Openness and reserve coexist. The head’s slight turn and the guarded gaze suggest inward concentration—perhaps the mental discipline required to hold a demanding pose, perhaps the artist’s own reflective mood transposed onto the sitter. The lighting heightens this ambiguity: one side open to illumination, the other sheltering shadow.

Relation to the Nice Period Interiors

Placed alongside the patterned rooms and reclining nudes of 1919–1921, this study reads as an anchor. The Nice interiors show Matisse orchestrating color fields and decorative rhythms; “Kneeling Nude” shows him re-grounding those pleasures in the grammar of weight and structure. The two strands are complementary. The clarity he achieves here—big masses, clean turns, a disciplined palette—supports the airy harmonies of the balcony scenes and odalisques. Without this sculptural rigor, the decorative could drift; with it, even the lightest curtain or pink couch sits with conviction.

How to Look

A fruitful way to see the painting is to follow the light as if it were a sculptor’s finger. Begin at the left shoulder where the brightest patch crowns the deltoid; travel down across the chest to the tight plane above the navel; slide along the oblique to the hip; then leap to the gleam on the shin. Reverse course by tracing the shadow seams that undercut those planes—the arc beneath the ribs, the pocket at the elbow, the fold at the groin. This path makes palpable how the figure is built and how the eye is meant to move. It also reveals the musicality of the composition: strong beats at shoulder and knee, quieter measures across abdomen and thigh, a syncopated pause at the face.

Material Ethics and the Visible Hand

Matisse’s decision to leave strokes open and joins visible is not merely aesthetic; it declares a value system. The painting does not pretend to be anything other than paint, yet it also refuses irony. The body is present and dignified; the artist’s touch is frank and accountable. That combination—respect for subject and for medium—gives the work its steadiness. In a moment of cultural repair after war, such steadiness matters. The painting offers solidity without heaviness, clarity without coldness.

Legacy and Foreshadowing

This canvas foreshadows the later distillations of the 1930s and the cut-outs of the 1940s. The insistence on silhouette against a luminous ground anticipates the great paper figures; the simplification of planes points toward a language of shape that will later be freed from modeling altogether. At the same time, “Kneeling Nude” preserves the tactile knowledge of the body that keeps Matisse’s abstraction humane. Even when color becomes pure paper, the memory of how light rounds a rib or tightens a knee persists, and it persists because of studies like this one.

Conclusion

“Kneeling Nude” compresses Matisse’s gifts into a single, urgent image. It is a sculptor’s painting and a painter’s sculpture, a study of mass animated by light, and a modern figure built from ancient rhythms. With a restricted palette and a disciplined composition, Matisse brings the body close and gives it gravity. The brush declares each decision, the contour breathes, and the background offers just enough theater for the form to stand forward. In a year defined by recovery and recalibration, the painting demonstrates how strength can be rediscovered through essentials: light, line, weight, and the living presence of a human figure.