Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

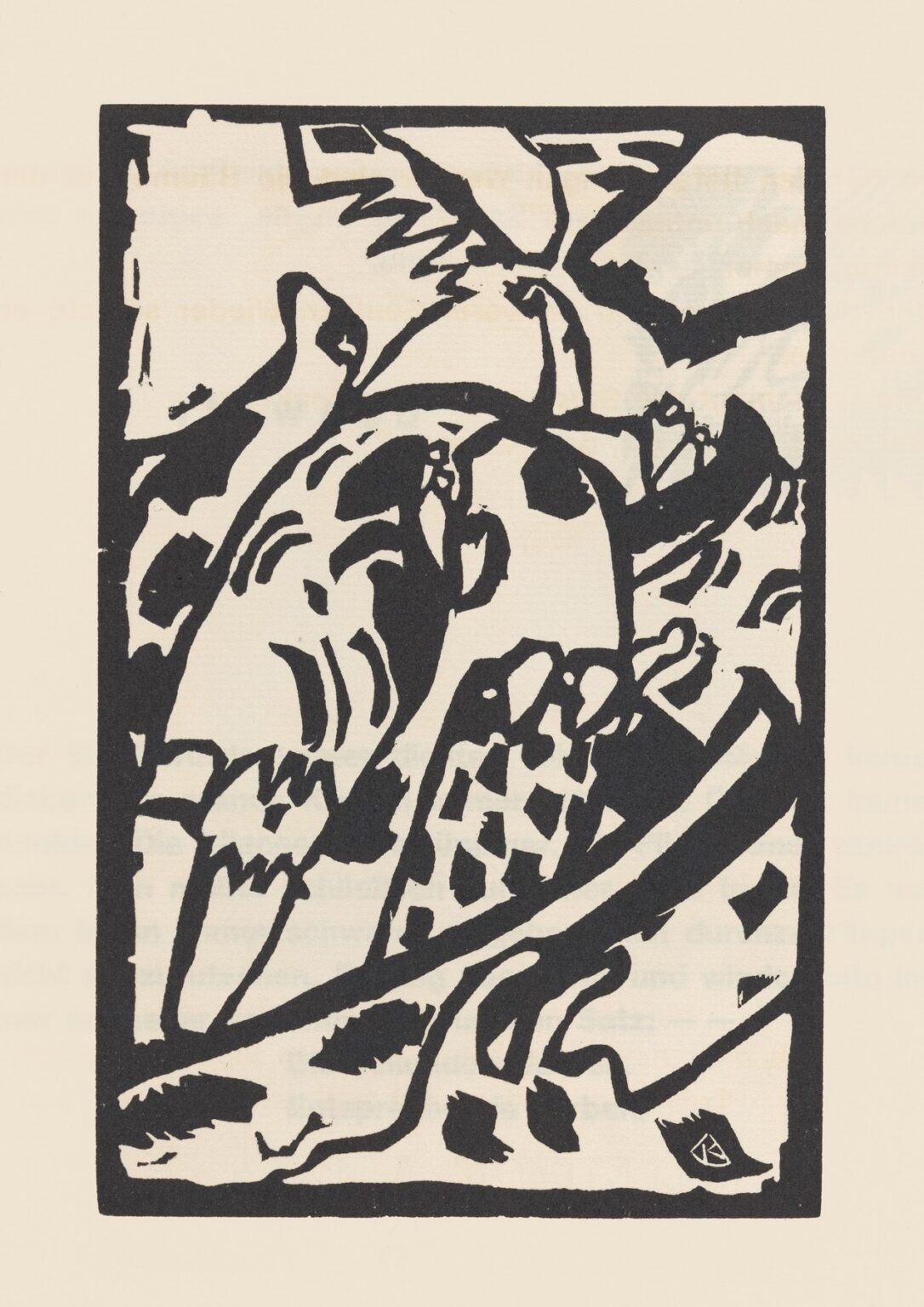

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 25 (1913) stands as a striking example of early abstract woodcut printmaking, marrying bold graphic contrasts with evocative forms that hint at musicality and spiritual depth. Executed as part of the Klänge (“Sounds”) portfolio, Plate 25 offers a dynamic interplay of black and white shapes, fragmented silhouettes, and rhythmic patterns that defy literal representation. At first glance, the woodcut’s angular shards and curved arcs seem spontaneous and unmoored, yet a closer look reveals a carefully orchestrated balance of positive and negative space. Through layers of abstraction, Kandinsky invites viewers into a visual symphony, where each line and form resonates like a musical note. In this analysis, we will explore the historical circumstances surrounding Klänge, Kandinsky’s evolving artistic philosophy, and the technical, formal, and symbolic dimensions that make Plate 25 a milestone in modern art.

Historical Context

The year 1913 marked a period of profound innovation and tension in Europe. In art, movements such as Cubism, Futurism, and Expressionism were redefining the very notion of representation, responding to rapid industrialization, urban expansion, and shifting social orders. Kandinsky, as a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter in Munich, was at the forefront of these avant‑garde dialogues, believing that art could transcend material reality and access spiritual truths. At the same time, printmaking offered an accessible medium for disseminating radical ideas beyond gallery walls. The Klänge portfolio—comprised of 30 woodcuts created between 1911 and 1913—embodied Kandinsky’s ambition to fuse visual art with the experiential qualities of music. In choosing a black‑and‑white scheme for Plate 25, he aligned with the German Expressionist ethos of raw emotional directness and the belief that simplified means could yield intensified impact. Klänge Pl. 25 thus emerged from a pre‑war ferment of experimentation, poised on the brink of global upheaval that would soon reshape Europe.

Artist Background

Born in Moscow in 1866, Wassily Kandinsky initially pursued law and economics before turning decisively to art in his thirties. After relocating to Munich in 1896, he immersed himself in plein air painting and the Symbolist influences of Munch and Van Gogh. By 1911, Kandinsky’s work had shifted markedly toward abstraction, driven by a conviction that color and form carried intrinsic spiritual and emotional force. He co‑founded the Der Blaue Reiter group in 1911, emphasizing art’s ability to convey inner necessity rather than mere imitation of the external world. In 1912, Kandinsky published Über das Geistige in der Kunst (“On the Spiritual in Art”), a treatise outlining his theories on color and form as synesthetic vehicles. The Klänge woodcuts, produced alongside his canvases, represented a logical extension of these ideas into a graphic medium. By Plate 25, Kandinsky had honed his visual vocabulary to a point where abstraction could evoke not only sensation but structured rhythm—an echo of musical composition rendered in stark contrasts.

The Klänge Portfolio

Klänge (“Sounds”) is a landmark series of woodcuts that Kandinsky began in late 1911 and completed by mid‑1913. Unlike his previous graphic work, which often mimicked natural forms, Klänge plunged fully into abstraction, seeking to translate auditory experience into visual terms. Each plate bears no figurative reference but rather suggests dynamic interaction—overlapping shapes, pulsating lines, and spatial tension. Plate 25, with its sparse field and jagged black motifs, marks a high point in the series’ progression toward pure abstraction. The portfolio was first exhibited in Munich in 1913, accompanied by musical performances, underscoring Kandinsky’s belief in a total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk). Although the series did not achieve immediate commercial success, it influenced contemporaries in Expressionism and later abstractionists, including the Bauhaus circle where Kandinsky would teach after World War I.

Formal Elements: Composition and Line

In Plate 25, Kandinsky orchestrates composition through a network of bold, unmodulated black shapes set against the white of the paper. The overall format is a tightly cropped rectangle that frames the visual interplay without peripheral distraction. Dominant diagonals—thick zigzag strokes across the upper register—impose a sense of upward energy, while rounded forms in the central area introduce moments of repose. Thin, calligraphic lines link disparate shapes, guiding the viewer’s eye through a rhythmic circuit. The deliberate asymmetry prevents monotony: no quadrant is static, yet the balance is maintained as darker masses on the right counterweight lighter clusters on the left. This masterful control of positive and negative spaces renders the print dynamic and unified, inviting prolonged contemplation of the invisible harmonies beneath its austere surface.

Contrast and Negative Space

The stark black‑on‑white contrast of Klänge Pl. 25 intensifies the impact of its forms. Kandinsky exploits negative space not as mere background but as an active participant in the composition. Voids between shapes allow the eye to rest and refract the black areas like a silent chorus. The interplay of figure and ground becomes a visual echo, where edges vibrate with implied movement. In certain areas, black masses nearly merge, suggesting chordal unisons; in others, narrow white filaments pierce through darkness, like solo voices emerging from a dense ensemble. This dialectic of light and dark—reminiscent of early woodcut expressionist prints—imbues the image with emotional charge, while preserving clarity of structure. Kandinsky’s use of negative space thus transcends mere separation, becoming a dynamic counterpart to the bold strokes that define the print’s character.

Rhythmic Abstraction and Musical Analogy

True to its title, Klänge Pl. 25 resonates with rhythmic abstraction, inviting analogies to music. The repetition of angular and curved forms functions like recurring thematic motifs in a composition. Rapid, staccato marks evoke percussion, while sustained diagonal runs suggest strings or winds. Viewers may sense crescendos and decrescendos as shapes expand or contract in visual volume. Kandinsky believed that sight and hearing share neurological pathways, enabling synesthetic experiences whereby colors and lines translate to tones or timbres. In Plate 25, the absence of color directs full attention to form and rhythm: the print becomes a silent fugue, where time passes through the eye’s journey across the motifs. This musical parallel underscores Kandinsky’s vision of art as an immersive, multi‑sensory event—one that dissolves boundaries between disciplines.

Symbolism and Interpretation

Although non‑representational, Plate 25 can yield rich interpretive layers. The jagged, arrow‑like forms in the upper section might symbolize upward aspiration or spiritual striving, consistent with Kandinsky’s belief in art’s transcendental purpose. The central curvilinear mass could represent a focal point of equilibrium—a visual anchor amid chaos—suggesting the search for inner balance. Fragmented, organic shapes at the bottom recall scattered leaves or petals, implying cycles of growth and decay. The woodcut medium itself—rooted in traditional printmaking—serves as a bridge between past conventions and radical new forms. Viewers attuned to Theosophical or Anthroposophical philosophies, which Kandinsky studied, might see echoes of cosmic forces, energies, or chakras. Yet these readings remain open, as Kandinsky himself resisted fixed interpretations, preferring works to function as catalysts for individual emotional and spiritual response.

Emotional Resonance

What ensures Plate 25’s enduring power is its capacity to evoke emotional movement without figurative anchors. Viewers often report feelings of exhilaration, tension, or quiet contemplation as they trace the print’s interlocking shapes. The visual oscillation between stability and fragmentation mirrors inner psychological rhythms—moments of clarity and moments of dissonance. Because the image lacks narrative specificity, it invites each person’s projection of personal associations: for some, the diagonal shards signal a tempest; for others, the curved forms embody gentle pulses of life. Kandinsky’s mastery lies in generating affect through pure form: the black shapes, in their urgency and restraint, speak directly to the viewer’s unconscious, proving that abstraction can convey as much emotional richness as representation.

Legacy and Influence

Klänge Pl. 25 stands as a cornerstone in the development of abstract art and graphic design. Its rigorous approach to composition and its emphasis on spiritual resonance influenced the Bauhaus curriculum, where Kandinsky later taught, emphasizing the unity of art, architecture, and design. European avant‑garde movements such as De Stijl and Russian Constructivism drew inspiration from his abstractions—particularly his use of geometric and organic shapes to articulate inner necessity. In the realm of printmaking, Klänge anticipated mid‑century explorations in linocut and serigraphy by artists seeking the potent immediacy of stark contrast. Today, Plate 25 is studied not only for its historical importance but also for its capacity to teach fundamentals of design: balance, rhythm, contrast, and the power of reductive means.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 25 (1913) remains a landmark in the history of abstract art—a woodcut that fuses formal rigor with emotive depth. Through its bold interplay of black and white shapes, dynamic composition, and rhythmic energy, the print transcends literal meaning to offer a visual symphony of spiritual and emotional resonance. Created in a turbulent pre‑war Europe, Plate 25 channels the era’s yearning for new modes of expression, exemplifying Kandinsky’s conviction that art could bridge matter and spirit. Its influence reverberated through subsequent generations of painters, designers, and printmakers, affirming the power of abstraction to communicate universals of human experience. Over a century later, Klänge Pl. 25 continues to inspire, inviting viewers to listen with their eyes to the symphonic interplay of line and form.