Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

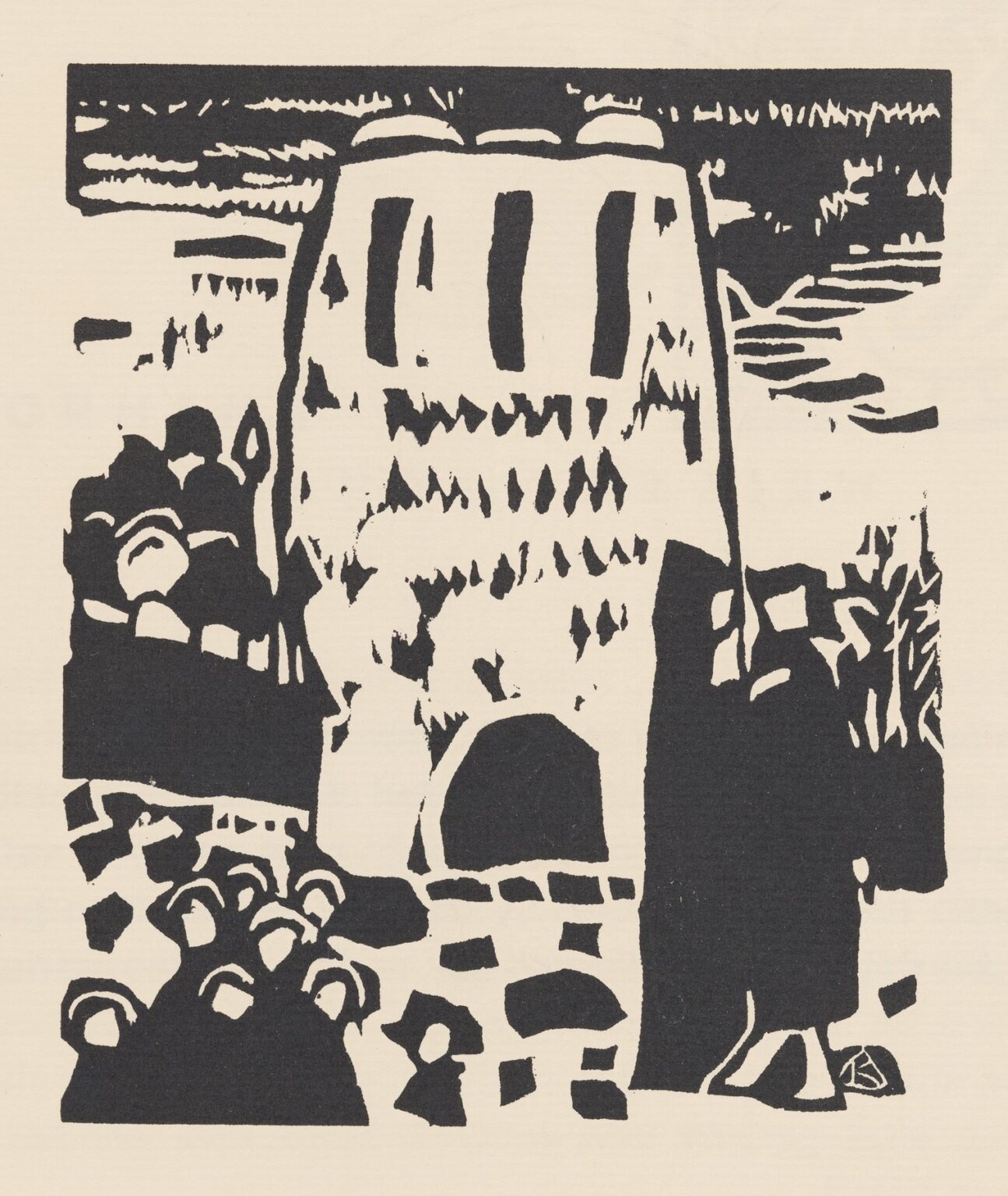

In Klänge Pl. 22 (1913), Wassily Kandinsky brought his pioneering spirit into the domain of graphic art, fashioning a woodcut that resonates like a silent percussion ensemble. The composition arrests the eye with its stark black‑and‑white contrasts: a towering central form, roughly rectangular, seems to pulse with energy, its surface broken by rhythmic, triangular marks that recall musical staccato. Flanking this dominant mass are clusters of more organic silhouettes—rounded nodules in the lower left, contrapuntal linear shards at upper right—that play off the central motif as though improvising around a fixed refrain. Yet Kandinsky’s woodcut is no mere exercise in decoration. It encapsulates his lifelong conviction that art could transcend representational boundaries to evoke spiritual and emotional vibrations akin to those produced by music. Through a sustained economy of means—no color, no receding perspective, no anecdotal content—Plate 22 offers a distilled encounter with rhythm and form, inviting viewers to “hear” the movement of shapes and to feel the heartbeat of abstraction itself.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1913, Kandinsky had already established himself as one of the leading voices of European modernism. His move from Moscow to Munich in 1896 ushered in years of study and stylistic evolution. Early plein-air landscapes gradually gave way to Symbolist and Post‑Impressionist influences, and by the first decade of the 20th century, Kandinsky had abandoned literal representation in favor of pure abstraction. His 1912 manifesto, Über das Geistige in der Kunst (“On the Spiritual in Art”), articulated a bold vision: color and form, liberated from the demands of mimetic depiction, could directly communicate the artist’s innermost state and reach the viewer’s soul.

Parallel to his oil painting practice, Kandinsky explored printmaking as a medium capable of distributing radical abstract imagery more widely. The Klänge series, created between late 1911 and mid‑1913, represented an ambitious foray into woodcut print. Unlike his canvases—where vivid hues and layered brushwork dominated—woodcuts necessitated a stark reduction to positive and negative shapes carved into blocks of wood. Kandinsky embraced these constraints, seeing in them an opportunity to further distill his visual language and to forge a deeper connection between rhythm, line, and spiritual resonance. Plate 22 emerged in the final phase of this experiment, its complex yet controlled layout reflecting both the influence of German Expressionism and Kandinsky’s burgeoning commitment to formal abstraction.

Kandinsky’s Philosophical Underpinnings

Central to understanding Klänge Pl. 22 is Kandinsky’s belief in the synesthetic unity of the arts—a conviction that painting could be experienced as music and vice versa. He often borrowed musical terminology to describe his compositions: “improvisations,” “compositions,” and in this case, “sounds.” For Kandinsky, lines could sing and shapes could strike chords; color could hum in low register or erupt in brilliant forte. Even in the monochrome world of woodcut, he sought to capture this musicality through the orchestration of forms.

Moreover, Kandinsky was deeply influenced by Theosophy and Anthroposophy, spiritual movements that posited a hidden, universal realm beneath the physical world. He saw abstraction as a means to access this invisible dimension, to render the vibrations of the soul on paper or canvas. In Klänge Pl. 22, the jagged triangular marks at the center might signify ascendant spiritual impulses; the rounded forms at lower left could represent grounding forces of earthly humanity. The work thus becomes a map of spiritual energies, articulated through the dynamic tension of black and white.

Formal Analysis: Structure and Composition

At first glance, Plate 22 appears to be an arbitrary jumble of shapes, but a closer look reveals a rigorous compositional architecture. The print divides into several visual zones without succumbing to fragmentation. A broad, upright rectangle dominates the middle, its top edge close to the picture plane’s upper boundary. Within this rectangle, a repeating pattern of dark, triangular notches—set against the white of the wood—creates an internal rhythm. These marks appear as descending rows, echoing the idea of musical notes cascading across a stave.

To the left of this central block, a cluster of semicircular shapes spills toward the lower left corner. These rounded masses contrast the angular rectilinearity of the central motif, much like a woodwind counter‑melody diverges from a main theme. On the right side, a vertical shard-like column interrupts the rectangle, suggesting the intrusion of an independent line or the entry of a solo instrument. Above and behind these primary elements, smaller slashes and zigzags fill the upper margin with whisper‑quiet echoes, imbuing the composition with depth and unifying the disparate parts through subtle reiteration.

Throughout the print, the interplay of black and white—the positive carvings and the negative spaces—functions as a visual counterpart to call and response. The viewer’s eye alternates between the weight of dark forms and the breath of surrounding emptiness, much as a music listener alternates between sound and silence. The absence of any gradation forces attention onto the contours themselves, rendering every shape emblematic, every edge resonant.

Contrast, Tension, and Movement

Key to Plate 22’s vitality is Kandinsky’s masterful manipulation of contrast. The central vertical form presses forward, its mass solid and almost monolithic, yet its interior pattern of light and dark notches fractures its presence, inviting dynamic tension. The rounded group on the left feels buoyant yet destabilized by its loose boundary. On the right, the slender column of black against white functions as a hinge, capturing the viewer’s attention and then pivoting the gaze back into the center.

Movement in the print emerges not from literal depiction but from the directional force of shapes. The triangular notches seem to point downward, imparting gravity; the diagonal slashes in the top margin sweep horizontally, suggesting lateral motion; the lower semicircles, drawn close together, imply circular procession. Candles of negative white pathways thread between these shapes, linking them into a cohesive visual rhythm. The overall effect is of a silent fugue, each section contributing to an unfolding spatial-temporal experience.

Technical Mastery of Woodcut

Realizing such a composition in woodcut demanded both planning and boldness. Kandinsky first translated his design into a drawn sketch, then transferred it to a wood block. Using gouges and knives, he carved away the areas meant to remain white, leaving the intended black shapes in relief. Uniform inking and careful registration ensured that prints remained consistent across editions, though subtle variations in pressure and wood grain added organic texture.

The very process of carving heightened Kandinsky’s awareness of line purity. He was forced to simplify curves and angles, to reduce each form to its essential silhouette. The solidity of the black relief demanded confidence: any extraneous mark or hesitation would register starkly against the paper. Yet Kandinsky’s prints exhibit remarkable fluidity, as if the forms had sprung fully formed from the block rather than having been painstakingly sculpted. This paradox of premeditated spontaneity is at the heart of Plate 22’s allure.

Spiritual and Symbolic Resonances

For Kandinsky, abstraction carried spiritual weight. He believed that forms and colors could convey inner life and universal truths more directly than representational imagery. In Klänge Pl. 22, the repeated triangular notches have been read as symbolic sibilants or spiritual sparks descending into the material world. The semicircular group could be interpreted as a community of souls or a cluster of karmic echoes. The right-hand shard might represent the entry of divine inspiration into everyday experience. Kandinsky himself resisted overly literal readings, preferring viewers to bring their own associations to the work. Yet the print’s charged geometry invites reflection on the polarity of mind and body, the interplay of human thought and cosmic order.

Emotional and Psychological Impact

Despite—or perhaps because of—its abstract nature, Plate 22 has an immediate emotional power. The starkness of its contrasts can induce a sense of exhilaration or tension. The viewer may feel drawn into its deep black recesses or buoyed by the negative white expanses. Each individual will respond differently, guided by personal temperament and associative memory. For some, the print’s angular forms will evoke the jagged thrill of a wind‑blown landscape; for others, the rounded shapes may prompt memories of communal gatherings or childhood games. Kandinsky’s genius lay in crafting a visual language that triggers such resonances without prescribing them, opening a space for subjective communion with the work.

Place Within Kandinsky’s Oeuvre

Klänge Pl. 22 occupies a unique position at the crossroads of Kandinsky’s painting and his graphic work. Its abstraction rivals his most daring canvases of the same period—such as Composition VII (1913)—but its black‑and‑white format highlights structural concerns that color in painting can sometimes obscure. The Klänge series as a whole functioned as Kandinsky’s laboratory for probing the essentials of abstraction: how might rhythm be conveyed without hue? How could form itself carry spiritual meaning? Plate 22 stands among the most accomplished results of this inquiry, its compact energy distilling lessons that would later inform Kandinsky’s teaching at the Bauhaus and shape the course of 20th‑century abstraction.

Legacy and Influence

The Klänge woodcuts have exerted a profound influence on artists and designers who followed. The emphasis on dynamic black‑and‑white patterning resonated with German Expressionist printmakers and later inspired the stark graphic designs of 20th‑century posters and album covers. Kandinsky’s belief in the spiritual potential of abstract form paved the way for the Abstract Expressionists in America, who likewise sought direct, unmediated expression through shape and gesture. In contemporary times, Plate 22 continues to be studied for its exemplary use of negative space, rhythmic composition, and synesthetic ambition. Its ability to engage viewers in a silent yet potent dialogue between form and feeling ensures its place as a timeless milestone in the history of modern art.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 22 (1913) represents a masterful convergence of spiritual theory, musical analogy, and graphic innovation. In its striking black‑and‑white abstraction, the woodcut transcends literal depiction to become a visual symphony of lines, angles, and voids. Through a carefully calibrated balance of contrast and rhythm, Kandinsky invites viewers into an immersive experience that bypasses narrative and speaks directly to the psyche. Positioned at the apex of his Klänge experiments, Plate 22 encapsulates Kandinsky’s conviction that art, like music, can reveal hidden harmonies and stir profound emotional responses. More than a century after its creation, Klänge Pl. 22 endures as a powerful testament to abstraction’s capacity to resonate across time, culture, and individual perception.