Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

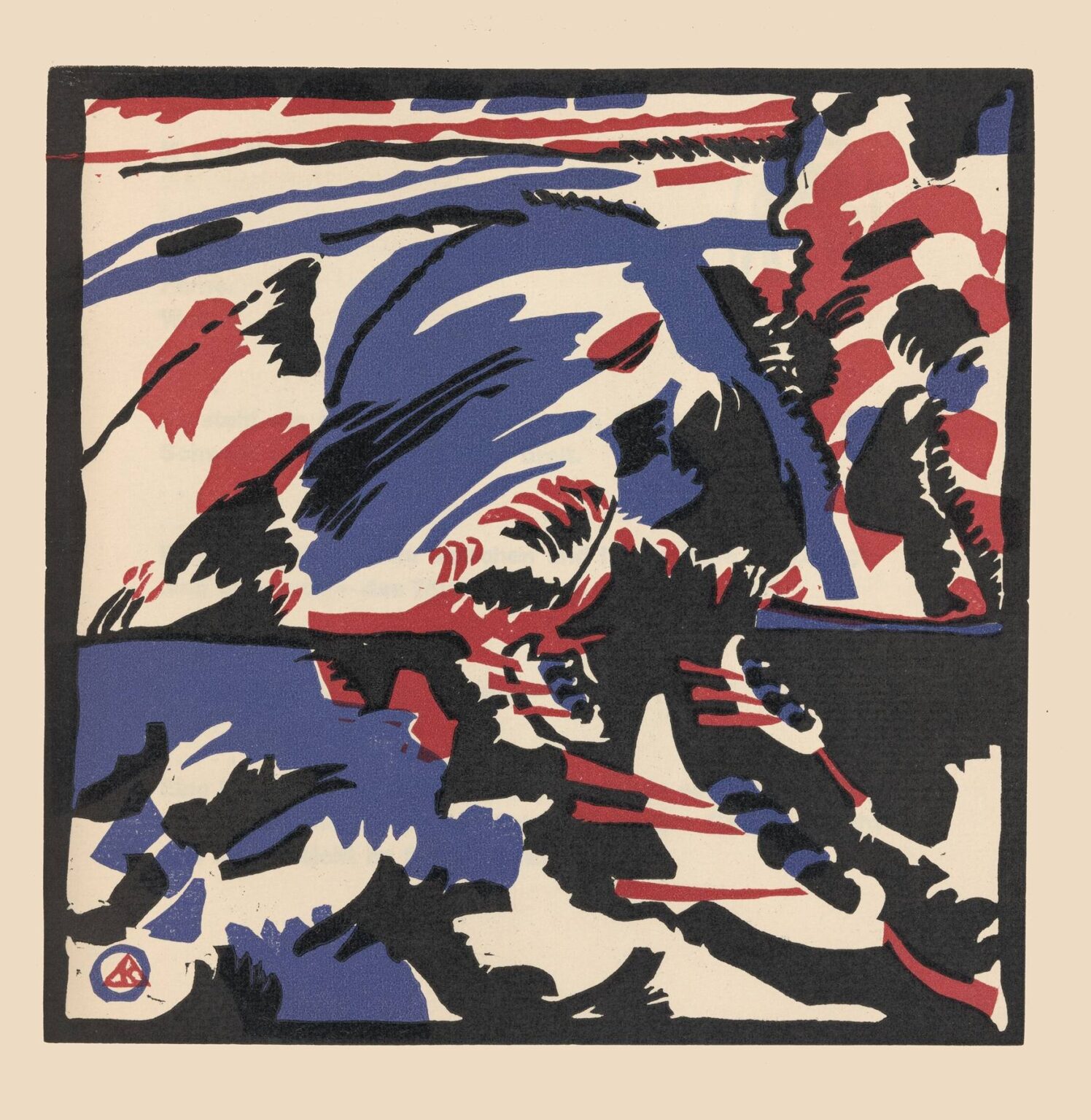

In Klänge Pl. 12 (1913), Wassily Kandinsky refines his exploration of synesthetic abstraction through the medium of woodcut print. The twelfth plate in his Klänge (“Sounds”) series captures an electrifying interplay of dynamic forms, textured voids, and chiselled accents that seem to hum with invisible resonance. Stripped of any representational subject matter, the print presents a stark black relief atop a warm ivory ground, enlivened by judicious overlays of crimson and ultramarine. Viewers are drawn into an internal dialogue between bold sweeps and intricate notations, where every carved notch and colored wash acts as a musical gesture. This analysis will trace the historical and spiritual impulses behind Kandinsky’s Klänge series, dissect the formal architecture and rhythmic strategies of Plate 12, illuminate its technical mastery, and uncover the emotional and symbolic undercurrents that continue to captivate audiences today.

The Spiritual and Cultural Context

In the early 1910s, Kandinsky found himself at the epicenter of a converging wave of artistic experimentation in Munich. The formation of the Der Blaue Reiter group in 1911 marked a decisive rupture with traditional training and representational art. He and his fellow avant‑garde artists sought to reinstate art’s spiritual dimension, believing that pure abstraction could directly communicate inner necessity. Kandinsky’s landmark treatise Über das Geistige in der Kunst (“On the Spiritual in Art,” 1912) articulated his conviction that geometric shapes and pure color harbored inherent emotional and metaphysical powers. Underpinning these theories was a fascination with Theosophy and the notion that art could act as a conduit between the material and the transcendent. The Klänge woodcuts, carved between 1911 and 1913, offered a new vehicle for these ideas: the hands‑on tactility of block printing allowed Kandinsky to combine the stark drama of black‑and‑white relief with the subtlety of hand‑applied color washes, creating an intimate yet powerful forum for spiritual resonance.

Synesthesia and Musical Analogy

Kandinsky’s writings frequently likened painting to music. He believed that just as notes combine to form melodies capable of stirring the soul, so too could abstract forms and colors orchestrate visual harmonies. His use of musical terminology—“compositions,” “improvisations,” and “sounds”—signaled his desire to transcend the boundaries of static image. In Klänge Pl. 12, the visual elements are arranged as if on a musical staff: broad black bands provide grounding bass notes, while slender carved hatchings punctuate the composition like staccato beats. Crimson overlays add a lyrical counterpoint, and ultramarine accents introduce a rich soprano timbre. This synesthetic blueprint invites viewers to “hear” the woodcut’s rhythms, to sense crescendos in the swelling black arcs, and to experience the silent resonances in the empty ivory spaces. Kandinsky’s ambition was nothing less than to create a “visual music” that communicates directly with the inner ear of the soul.

Formal Architecture and Composition

Klänge Pl. 12 unfolds within a precise square frame carved in deep relief. The top edge features a sinuous black arc that tapers into a slender tail, evoking the sweep of a conductor’s baton or the curve of a string instrument’s body. Beneath this arch, a network of fragmented black patches scatters diagonally across the middle register, as though embers drifting in a thermal current. Towards the lower portion, a thick horizontal black band anchors the print, its even plateau contrasting the jagged dynamism above. Nestled against the right border, a vertical cascade of five carved triangular voids rises like a stylized solfège scale, each triangular notch slightly larger than the one below—a visual crescendo ascending toward the midline. Interstitial pockets of untouched paper punctuate the relief shapes, allowing the ivory ground to breathe and to act as resonant silence between sonic bursts.

Color Application and Tonal Contrast

Unlike earlier Klänge plates that remained purely monochrome, Plate 12 integrates hand‑applied watercolor overlays in two principal hues: a vivid cadmium red and a deep ultramarine blue. The red appears in discrete brushstrokes atop the upper arc and in select fissures of the middle embers, as though marking moments of fiery intensity. Ultramarine washes mingle with black relief in the lower register, enhancing the textural depth of the horizontal band and shimmering through thin carved hatchings. These color interventions are applied with restraint, never obscuring the carved lines but rather animating them. The pigment’s slight graininess and occasional pooling at relief edges testify to the organic variability of handwork, reminding viewers that the print is born of both mechanical carving and human touch. The warm ivory of the paper ground further contributes to tonal richness, softening the transition between black relief and colored accents and unifying the composition in a gentle glow.

Rhythm, Movement, and Visual Pulse

At the heart of Klänge Pl. 12 lies an intricate choreography of visual pulse. The undulating arc at the top sets a sweeping gesture, guiding the eye from left to right. From there, the scattered black fragments create a staccato rhythm, each patch acting like a percussive strike. The viewer’s gaze is then drawn downwards to the rising triangles on the right—an ascending motif that suggests melodic progression. Finally, the thick horizontal band at the bottom provides a final repose, a base note that resonates under the ear. This cyclical journey—from arc to fragments to triangles to band—establishes a looped sequence, inviting prolonged engagement. Minute carved hatchings nestled among the larger forms offer shimmering embellishments—trills and grace notes—that enliven the main voices and reward close scrutiny with subtle surprises.

Spatial Ambiguity and Layering

Although lacking conventional perspective, Plate 12 achieves a compelling sense of depth through the interplay of relief and void. The black shapes appear to hover above the ivory ground, casting implied shadows at their carved edges. Certain fragments overlap lightly, suggesting that they reside on different planes. The triangular voids on the right arc forward, as though lifted from the main mass, their crisp white forms projecting toward the viewer. Crimson and ultramarine washes add further stratification: the red sits atop the black relief, while the blue seems to saturate interstitial channels behind carved lines. This layering of ink, pigment, and paper creates a spatial architecture that feels dynamic and theatrical, transforming the print into a stage where forms perform an eternal dance between foreground and background.

Technical Mastery of Woodcut

Woodcut carving demands precision, planning, and confidence: every cut is irreversible. In Plate 12, Kandinsky demonstrates consummate control over his tools. The thick border and bold arcs bear the mark of confident gouge work, yielding smooth, consistent relief. The jagged fragments retain clean edges, indicating careful incision along grain direction. The array of triangular voids exhibits remarkable uniformity in both shape and spacing, a testament to painstaking measurement. The fine hatchings nestled among the black shapes were likely executed with a small V‑tool, each line maintaining consistent width and depth. After carving, the block was inked evenly—no blotches or gaps disrupt the black fields—before being impressed onto high‑quality, slightly textured paper. The subsequent watercolor application required exact registration: neither the red nor the blue encroaches on unintended areas, preserving the integrity of the carved lines. These technical achievements underscore Kandinsky’s dedication to mastering both the mechanical and painterly aspects of relief printing.

Symbolic and Emotional Resonance

Beyond its formal virtuosity, Klänge Pl. 12 pulsates with symbolic undertones. The sweeping arc at the top can be read as a protective canopy or a cosmic horizon, hinting at the transcendent realms Kandinsky sought to evoke. The scattered fragments suggest sparks of inspiration or fleeting glimpses of spiritual insight, while the ascending triangles on the right embody the soul’s aspiration toward higher planes. The horizontal anchor below grounds the print in earthly reality, reminding the viewer of the interplay between the mundane and the mystical. Emotionally, the print evokes both tension and release: the embers flicker with latent energy, while the rising scale offers reassurance of progression and uplift. Kandinsky believed that abstract forms could directly stir the viewer’s innermost feelings, and Plate 12 stands as a powerful example of that capacity.

Relation Within the Klänge Series

Klänge Pl. 12 occupies a pivotal position in the series, bridging the purely monochrome experiments of the early plates with the boldly colored reliefs of the later ones. Compared to Plate 10’s austere black‑and‑white austerity and Plate 13’s richer color overlays, Plate 12 achieves a harmonious synthesis: its color is neither too sparing nor too exuberant, its carving neither too raw nor too refined. The motifs of arcs, scatterings, and rising scales recur throughout the series, but in Plate 12 they coalesce into a singularly balanced composition. It exemplifies Kandinsky’s evolving mastery of printmaking as a medium for spiritual abstraction, prefiguring his later fully chromatic woodcuts and his celebrated oil‑on‑canvas Compositions of the 1913–1914 period.

Influence and Legacy

Over a century since its creation, Klänge Pl. 12 continues to inspire artists, musicians, and theorists exploring the intersections of sound and image. Printmakers study its carving techniques and pigment registrations as benchmarks of craft. Graphic designers draw on its rhythmic interplay of positive and negative space for layouts that evoke visual music. Performers have staged live concerts juxtaposed with projections of Klänge plates to explore synesthesia in contemporary performance art. In academia, Kandinsky’s woodcuts remain central to studies of abstraction’s spiritual dimensions, illustrating how non‑representational art opened new pathways for emotional and metaphysical engagement. Plate 12, with its consummate blend of formal rigor and impassioned vision, stands as one of the series’ most enduring landmarks.

Conclusion

Wassily Kandinsky’s Klänge Pl. 12 (1913) embodies the artist’s quest to fuse music, spirituality, and printmaking into a unified language of pure form. Within its square frame, bold black relief sweeps, fragments, and ascends in a visual fugue, enlivened by crimson and ultramarine accents. Technical mastery of carving and color application yields a composition that resonates with rhythmic energy and spiritual aspiration. Positioned at the heart of the Klänge series, Plate 12 perfectly encapsulates Kandinsky’s belief that abstraction can directly awaken the soul. Today, its silent symphony of shape and void continues to speak across the decades, inviting viewers to hear the vibrations of form and to partake in the transcendent echoes of early modernism.