Image source: artvee.com

Historical and Artistic Context

Walter Crane painted King Cole in 1876, during the height of the English Aesthetic Movement and the Golden Age of Illustration. This period, spanning roughly from 1860 to 1910, saw the flowering of decorative arts, children’s books, and richly ornamented design. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had recently challenged the rigid conventions of academic painting, advocating instead for vivid color, intricate detail, and moral or literary subject matter. Meanwhile, Queen Victoria’s reign fostered a booming publishing industry, with authors like Lewis Carroll and illustrators such as John Tenniel and Randolph Caldecott transforming the book into a work of art. Crane—trained at the South Kensington School of Art and influenced by Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament—merged socialist ideals (he was a lifelong friend of William Morris) with an abiding passion for decorative pattern. His King Cole sits at the intersection of fine art, decorative design, and children’s literature, embodying the Aesthetic dictum that “art for art’s sake” can nonetheless serve a moral or educative purpose.

The Nursery Rhyme and Its Origins

The title refers to the English nursery rhyme “Old King Cole,” which first appeared in print in the early 18th century. The verses read simply:

“Old King Cole was a merry old soul,

And a merry old soul was he;

He called for his pipe, and he called for his bowl,

And he called for his fiddlers three.”

Though short, the rhyme evokes a festive court scene where music, merriment, and conviviality reign. By the Victorian era, nursery rhymes had become a standard feature of children’s anthologies, often accompanied by elaborate wood-engravings or chromolithographs. For Crane, illustrating “Old King Cole” provided the opportunity to expand the brief verse into a rich visual tableau that celebrated music, decoration, and the spirit of innocent festivity.

Crane’s Life and Artistic Philosophy

Walter Crane (1845–1915) was born in Liverpool and apprenticed as a china painter before enrolling at the South Kensington School. He quickly gained renown for his watercolors, decorative panels, and book illustrations. A committed socialist and member of the Arts and Crafts movement, Crane believed that art should be integrated into everyday life—on wallpaper, ceramics, furniture, and books. He co-founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings and collaborated with William Morris on design commissions. Yet, unlike Morris’s medievalism, Crane’s imagery often drew on classical mythology, Japanese prints, and Gothic ornament. In his nursery rhyme illustrations, he combined these diverse influences with bold outlines, harmonious color schemes, and densely patterned borders, seeking to enthral young readers and elevate the status of children’s books to the level of fine art.

Subject Matter and Narrative Expansion

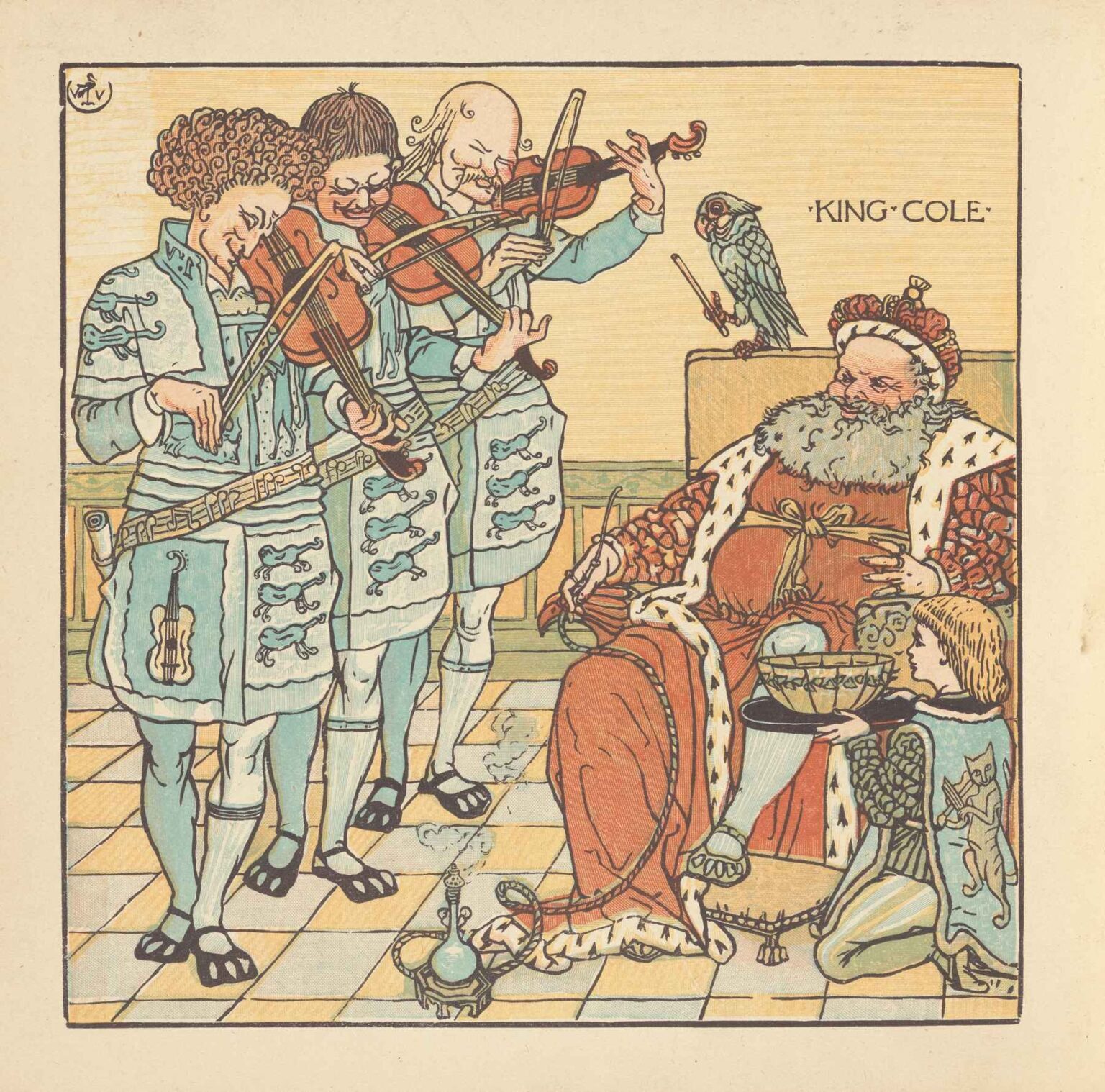

While the rhyme mentions only a pipe, a bowl, and three fiddlers, Crane’s illustration transforms the scene into a multi-figured court setting. At center, Old King Cole reclines on a sumptuous throne, crowned with an ermine-trimmed cap and cloaked in regal red velvet. His plump, benevolent face turns toward the three fiddlers—each caught mid-performance as they play identical violins. To the right, a small page kneels, holding a silver bowl on a platter—perhaps containing wine or punch—while a colorful parrot perched on the throne’s arm adds a whimsical flourish. The court floor’s checkerboard pattern grounds the scene, while a richly draped canopy of textile swirls overhead. Crane thus expands the sparse rhyme into a layered visual story, complete with attendant courtiers, decorative flourishes, and a sense of theatricality that invites the viewer to imagine the music’s melody and the king’s catchphrase, “Let us be merry!”

Composition and Spatial Organization

Crane arranges the scene within a nearly square frame, its borders filled with a flat beige ground that accentuates the internal riot of color. The king’s rightward gaze forms a gentle diagonal with the fiddlers at left, creating a visual dialogue between monarch and musicians. The three players overlap each other—leftmost to rightmost—establishing depth and a sense of forward movement, as though each successive fiddler advances slightly toward the viewer. The page with the bowl anchors the lower right, balancing the vertical thrust of the three musicians. The parrot’s diagonal perch counterpoints the row of fiddlers, while the canopy’s curved stripes echo the flowing lines of the king’s robe and the page’s tunic. This interplay of verticals, horizontals, and diagonals produces a dynamic yet stable composition befitting a festive court.

Use of Color and Pattern

Crane’s palette is rich and harmonious: the king’s red mantle and warm flesh tones contrast with the cool turquoise tunics of his musicians and the pale lemon backdrop. Subtle variations—pink highlights on cheek and robe, olive shading on leaves, gold etching on the bowl—add depth without disrupting the overall flatness prized by Aesthetic design. Ornamental pattern abounds: the king’s ermine trim, the filigree inlaid on the bowl and throne, the repeated motif of treble clefs dancing across the fiddlers’ doublets, and the lattice-like floor tiles beneath their feet. Even the clothing bears decorative devices—stylized leaves, curling tendrils—that echo Morris’s textile fantasy. Through these carefully arranged patterns, Crane transforms a simple rhyme into a tapestry of visual delight.

Line Work and Decorative Flourishes

Influenced by Japanese woodcuts (ukiyo-e) and Gothic manuscripts, Crane employed strong, flowing outlines to define figures and draperies. The fiddlers’ tuning pegs, bow hair, and scrollwork on the violin bodies are rendered with confident curves and hatchings. The canopy’s folds and the throne’s carved armrests feature rhythmic parallel lines that suggest embroidery and carving. Crane’s pen-and-ink work underlies the flat application of watercolor, ensuring that every shape reads clearly even against adjacent colors of similar hue. This blend of line and wash characterizes Crane’s mature style: a decorative surface that remains legible and harmonious even at reduced scale, making his illustrations eminently suited for mass printing.

Symbolic Resonances: Music, Merriment, and Authority

Beneath its decorative sheen, King Cole carries symbolic undertones. Music here is an instrument of both pleasure and power—kingly authority employs the fiddlers to validate his rule and entertain the court. The page presenting the bowl suggests ritual: the king is served, not as a private individual, but as a public figure sustained by spectacle. The parrot—an exotic pet—reinforces themes of leisure and colonial reach. The checkerboard floor, a symbol of order and societal structure, contains the dynamic fervor of performance within measured boundaries. Crane thus balances merriment and hierarchy, suggesting that even in joyful festivity, social roles and power dynamics remain at play.

Relation to Crane’s Broader Oeuvre

Crane’s King Cole forms part of a larger series of nursery rhyme illustrations that includes Humpty Dumpty, Little Bo-Peep, and Sing a Song of Sixpence. Each features similar hallmarks: dignified presentation of childlike subject matter, lavish costuming, and decorative borders. Beyond nursery rhymes, Crane illustrated Grimm’s Fairy Tales, Algernon Swinburne’s poetry, and Hans Christian Andersen’s stories—always applying his signature blend of Aesthetic design and moral sensibility. His decorative panels and wallpaper designs echo the motifs found here, demonstrating his belief in the unity of fine and applied arts. In sum, King Cole reflects both Crane’s political idealism—art for all—and his conviction that children’s books deserve the same artistic care as grand public murals.

Technical Execution and Reproduction

Crane’s original watercolors were reproduced via chromolithography, a complex printing process that layered multiple color stones to achieve nuanced hues. Early editions of The Baby’s Opera (1877) and The Baby’s Bouquet contained these prints, each plate framed by a printed border and accompanied by song lyrics or rhyme. The fidelity of the reprints to Crane’s originals testifies to the high standards of Victorian-era book production. Collectors today prize first editions for their crisp lines and rich colors. The technical demands of hand-registration in chromolithography required Crane to work within the limitations of the medium—large flat areas of color, precise alignment of plates, and minimal painterly blending—yet he turned these constraints into a bold, decorative style that remains instantly recognizable.

Reception, Influence, and Legacy

During Crane’s lifetime, his nursery rhyme books sold briskly among middle-class families. Critics lauded his integration of folk verse with sophisticated design, while some conservatives decried his departure from naturalistic illustration. Nevertheless, his work influenced countless later illustrators—Edmund Dulac, Beatrix Potter, and contemporary graphic novelists alike—who adopted his fusion of line, pattern, and narrative whimsy. The revival of interest in the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 20th century also led to a reassessment of Crane’s contributions, not only as a children’s illustrator but as a pioneering designer whose patterns and motifs continue to inspire wallpaper, ceramics, and textile lines.

Conclusion

Walter Crane’s King Cole transcends its status as a mere accompaniment to a nursery rhyme. It stands as a masterwork of the Aesthetic Movement, combining rich color, intricate pattern, and narrative depth within a compact, decorative tableau. Crane’s illustration celebrates the joy of music and the ritual of courtly hospitality, while subtly reminding viewers of the social roles and power structures underpinning even the simplest festive scene. Over 140 years after its creation, King Cole endures as a testament to Crane’s belief that art should elevate everyday experience—whether in a palace court or a child’s bedroom—into the realm of enchantment.