Image source: artvee.com

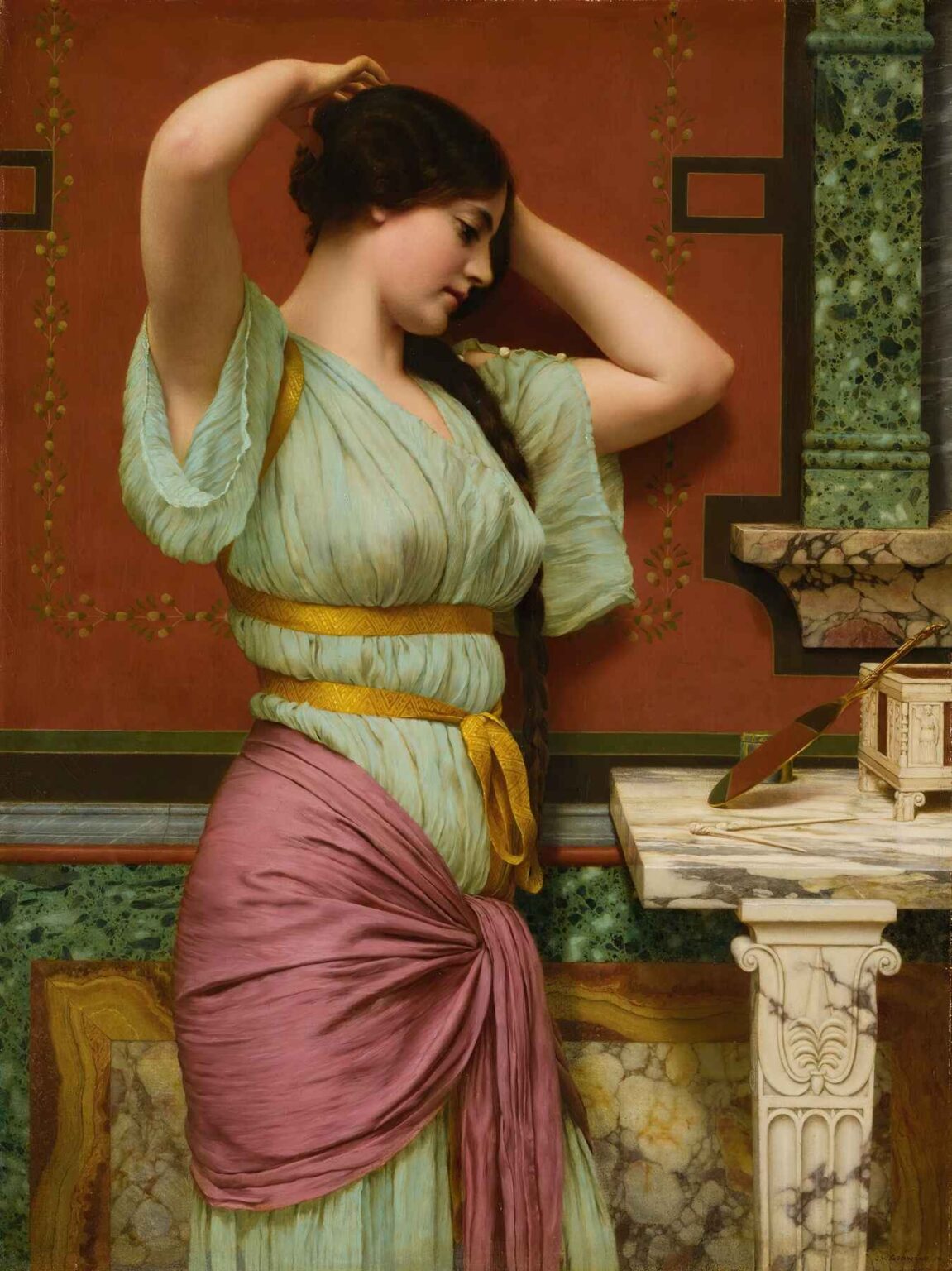

John William Godward’s Julia, painted in 1914, is a striking example of neoclassical portraiture infused with sensuality, refinement, and remarkable technical mastery. Created at the height of Godward’s career, this work exemplifies his unique ability to blend the aesthetics of classical antiquity with the ideals of Victorian beauty, executed through meticulous attention to detail and a restrained yet evocative sense of mood.

At a time when modernism was beginning to dominate the European art scene, Godward remained committed to classical traditions, resisting the tide of abstraction and innovation embraced by contemporaries like Picasso and Matisse. Instead, he chose to perfect his own niche: romanticizing the ancient world through the lens of Edwardian idealism. Julia is not merely a portrait of a woman, but a stylized vision of feminine grace, set against the opulent backdrop of imagined Roman luxury.

This analysis will explore the painting’s stylistic components, historical context, symbolic undertones, technical execution, and the ways in which Julia exemplifies Godward’s lifelong artistic project—a deliberate pursuit of timeless beauty in an era of rapid change.

Historical and Cultural Context

By the early 20th century, John William Godward was already seen as the last of the great Victorian classicists. Born in 1861 and strongly influenced by the works of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema and Frederic Leighton, Godward developed a career steeped in historical reconstruction and academic precision. His models were often imagined as priestesses, muses, or domestic figures from ancient Greece and Rome, and his paintings typically situated them in serene architectural settings composed of marble, mosaics, and drapery.

Julia was painted in 1914, on the eve of the First World War and at the end of the Edwardian period—a time characterized by elegance, social rigidity, and a nostalgia for classical ideals. Godward, increasingly alienated by the modernist movement’s growing prominence, relocated to Italy, where he could immerse himself in the classical settings that so deeply inspired him.

This cultural backdrop is essential to understanding Julia. It was not simply a reflection of contemporary taste, but a conscious counterpoint to it. Where the modernists aimed to fragment, distort, and innovate, Godward sought to preserve, beautify, and idealize. In this sense, Julia becomes a kind of artistic resistance—an homage to permanence in an age of upheaval.

Subject and Composition

The painting features a young woman, Julia, standing in a richly adorned Roman interior. She appears caught in an intimate moment of self-adornment, her arms raised as she adjusts her long, dark hair. Her gaze is turned downward, possibly directed at the small mirror or golden hairpin on the marble table beside her, though the viewer never fully accesses her eyes. This creates a sense of introspection and gentle self-absorption.

Julia’s pose is both naturalistic and classically sculptural. The lifted arms and subtle twist of the torso echo the contrapposto stance of Greco-Roman statues, while the softness of her expression and the delicate handling of fabric emphasize femininity and grace. She is surrounded by luxurious textures—green marble, onyx, polished stone, gold trim—and the entire setting speaks to a world of cultivated refinement.

This carefully orchestrated environment reinforces the timeless nature of the subject. Nothing in the painting ties Julia to any specific historical figure or moment; instead, she exists in a mythologized version of antiquity, idealized and eternal.

Fabric, Color, and Drapery

Godward’s ability to render fabric remains one of his most celebrated talents, and in Julia, that skill is on full display. The subject’s garment is a flowing robe of pale aquamarine, cinched at the waist with a golden sash. Over her hips, a sheer purple-pink wrap is tied into a loose knot, accentuating her figure while adding compositional dynamism through the diagonal sweep of its folds.

The color palette is soft but rich. The aquamarine of the dress harmonizes with the deep green marble and warm tones of the sienna wall behind her. The gentle transition from cool to warm hues is handled with subtlety, allowing the figure to stand out without jarring contrast. Gold highlights—in the sash, in the polished table accents, and on the jewelry box—catch the light in controlled bursts, enhancing the luxurious feel.

Godward’s drapery is not merely decorative. It emphasizes the contours of the body, guides the viewer’s eye through the composition, and serves as a foil for the solidity of the architecture. The folds and creases are painted with astonishing precision, with every ripple rendered as if caught mid-movement. This interplay of texture—fabric against marble, softness against hardness—adds depth and sensuality to the scene.

Architecture and Background Detailing

The backdrop of Julia plays a critical role in reinforcing the painting’s classical ambiance. The use of polychromatic marble, Corinthian columns, and geometric wall panels is reminiscent of actual Roman architecture, particularly the opulent interiors found in villas like those at Pompeii or Herculaneum. Godward was known to study ancient ruins and archaeological findings, and his commitment to architectural accuracy lends the scene an authenticity that transcends simple fantasy.

The composition’s right side features a beautifully rendered marble table, whose fluted legs and veined surface contrast elegantly with the woman’s figure. On the table sits a small box, perhaps a container for jewelry or cosmetics, and a mirror—a symbol of self-awareness and beauty, as well as an allusion to vanitas themes. Yet, unlike Baroque vanitas paintings that moralize about the transience of youth, Julia offers no such warning. It instead revels in the pleasures of appearance and self-presentation, detached from judgment.

Even the background wall, with its decorative vine motif and red plaster tone, contributes to the painting’s narrative by framing Julia within an idealized domestic space. The viewer is invited not into a bustling Roman street or public bath, but a quiet, refined interior where beauty is cultivated in private.

Feminine Beauty and Idealization

Julia, like many of Godward’s female subjects, represents an idealized vision of womanhood. She is poised, modest, and self-contained. Her interaction with the viewer is indirect—she does not make eye contact, and her absorbed pose renders her unaware of our presence. This creates a sense of voyeurism that is neither provocative nor intrusive, but contemplative.

Her beauty is classical rather than fashionable. She lacks the exaggerated corseting of Edwardian fashion or the modern stylization emerging in 1910s advertising. Instead, she is timeless—her proportions, features, and posture conform to the neoclassical ideals laid down by the Greeks and later refined in Renaissance and academic art.

Yet, while Julia’s beauty is clearly idealized, Godward resists turning her into an anonymous goddess. Her name gives her personality, and the naturalistic modeling of her features suggests that she may be based on a real studio model. There is humanity here, softened by idealism. Julia becomes a representation of personal grace rather than mythic archetype.

Technique and Execution

The technical execution of Julia demonstrates Godward at the peak of his abilities. His brushwork is virtually invisible—a hallmark of academic classicism—which contributes to the illusion of photographic clarity. The painting is so finely rendered that the textures of marble, hair, skin, and cloth each appear distinct, tactile, and wholly convincing.

The handling of light is equally refined. A diffuse, even illumination pervades the entire scene, casting soft shadows and creating a warm, golden tone. This lack of dramatic chiaroscuro is deliberate. It places the emphasis on surface, contour, and harmony, aligning with Godward’s focus on serenity and visual pleasure.

Edges are carefully controlled, transitions are gradual, and there is no trace of painterly bravura. This restraint, though unfashionable by modernist standards, reflects an almost obsessive pursuit of perfection—a desire to remove all signs of the artist’s hand and to present the subject as though seen through the clearest possible lens.

The Decline of Classicism and Godward’s Legacy

By the time Julia was completed in 1914, the art world was already shifting rapidly. The Armory Show had taken place in New York the previous year, introducing American audiences to Cubism, Fauvism, and abstraction. In Europe, artists were responding to industrialization, war, and psychology with radical new forms of expression. Godward, deeply traditional and personally reclusive, was left behind by these trends.

His commitment to classical aesthetics became increasingly out of step with the modern world. Tragically, Godward took his own life in 1922, reportedly lamenting that “the world is not big enough for me and a Picasso.” His death marked not just a personal loss but the symbolic end of the neoclassical tradition in painting.

And yet, Godward’s work has endured—not as a relic, but as a celebration of ideal beauty, craftsmanship, and timeless poise. In an age of visual overload, his paintings offer a meditative clarity that continues to captivate collectors and scholars alike. Julia remains one of the finest examples of his style, encapsulating the essence of his artistic mission with elegance and precision.

Conclusion: A Moment of Eternal Poise

Julia by John William Godward is far more than a decorative image. It is a masterful exercise in idealization, a testament to the enduring appeal of classical beauty, and a poignant marker of an artistic era drawing to a close. Through its exquisite composition, rich textures, and quiet introspection, the painting invites the viewer into a moment suspended outside of time—where the rituals of adornment, the harmony of form, and the pursuit of perfection are elevated to art.

Though painted during a period of artistic revolution, Julia remains steadfast in its commitment to serenity, balance, and grace. It is this quiet defiance of modern anxiety that makes the work resonate even today. Godward offers not escape, but an invitation to slow down, observe, and appreciate the eternal elegance of a figure lost in thought—a timeless muse in a world of marble and silk.