Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

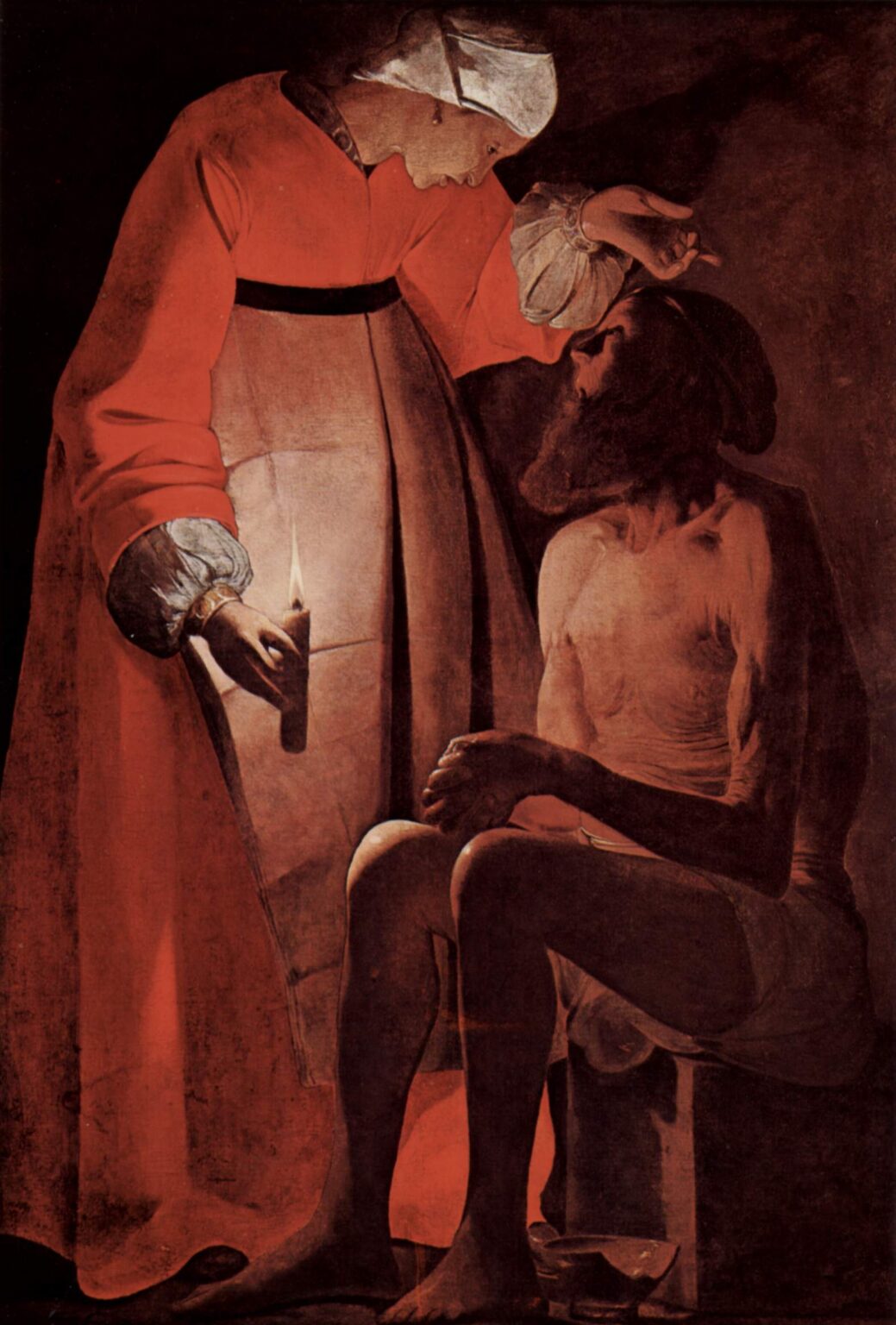

Georges de la Tour’s “Job Mocked by His Wife” (1635) stages one of the Bible’s most difficult conversations in a nocturne pared down to two bodies, a candle, and a chamber of shadow. Job sits nearly naked on a low block, his afflicted body reduced to muscle and bone. His wife looms above him in a cardinal-red gown, one hand lifting her head scarf in a gesture that reads as both emphasis and scorn, the other hand pinching a small candle whose flame carves the scene from darkness. No landscape, no onlookers, no narrative clutter interrupts the exchange. De la Tour distills the Book of Job’s furnace of questions to a single, intimate argument: a suffering man holding fast to faith, and a spouse who, exhausted by calamity, urges him to let it go.

Composition and the Architecture of Confrontation

The painting is built on a vertical dialogue. At left, Job’s wife is a tall, continuous column of color that drops from head to hem, a living wall that absorbs and directs the candle’s light. At right, Job is a compact mass of angled limbs, his knees lifted and his arms folded loosely over them, his head turned upward toward his accuser. The two forms meet along a steep diagonal defined by the fall of her sleeve and the incline of his jaw. That diagonal is the path of the argument. The candle sits at the hinge of their exchange, a wedge of light pushed forward by her hand so that it shines not merely on Job’s body but on the space between their faces. By arranging the figures like hinged planes, de la Tour transforms debate into architecture. The viewer’s gaze travels from the wife’s lifted hand to Job’s turned face, down to the candle, and back up the red wall of cloth, looping through the moral problem until the rhythm feels inexorable.

Chiaroscuro and the Invention of Moral Weather

De la Tour’s light is always ethical engine, and here it reaches a rare concentration. The small candle makes an outsized wedge of brightness because the painter shields it with the wife’s body, allowing light to rebound across the pale interior of her gown. This reflected glow softens the edges of her face and sleeve while striking Job’s skin with a drier, more unforgiving clarity. The result is a subtle asymmetry: she is wrapped by light she partly controls; he is examined by light he must endure. Darkness is not merely emptiness but witness, a surrounding quiet that registers the gravity of speech. Unlike Caravaggesque flash, de la Tour’s chiaroscuro is controlled and architectural; it does not dramatize violence but articulates conscience.

Costumes, Skin, and the Politics of Exposure

Clothing here is argument. The wife’s red robe, cinched with a dark sash, falls in long planes with little ornament, its severity undercut by the delicate cuffs and the bright headscarf she adjusts with a taut gesture. The robe’s mass makes her a mobile wall, a thing of authority. Job’s near-nudity, by contrast, exposes the ribs, the knotted shoulder, the knob of knee. His body is not eroticized; it is a ledger of attrition. In reducing him to skin and bone, de la Tour refuses sentimentality. Suffering is not theatrical sores and gore but the slow subtraction of flesh. Against that subtraction, the wife’s tailored presence reads as worldly efficacy, the sort of competence that wants results—any results—now.

Gesture as Scripture

De la Tour tells the story with two hands. The wife’s candle-hand is low and steady; her other hand arches over Job’s head, wrist bent, index finger extended in a contour that can be read as scolding, challenge, or weary insistence. Job’s hands are a counter-eloquence: the left loosely cups the right, a posture of listening more than self-defense. The hands hold the theological tension between provocation and patience. In the biblical text, she urges him to “curse God and die.” De la Tour avoids literalization and writes the imperative as a contour of fingers. Job’s answer—a refusal that is neither triumphant nor bitter—arrives in the measured calm of his folded hands.

Faces and the Psychology of Speech

The wife’s head bends forward, not backward; she leans into her words. The candle puckers the flesh of her cheek, sharpens the bridge of her nose, and leaves her eyes in half-shadow so that her expression hovers between compassion scalded by hardship and a practical person’s exasperation with metaphysical patience. Job’s face, furred by beard, is turned upward into a light that sympathizes with form but not with comfort. The hollow under his cheekbone and the crease at the corner of his mouth do the work usually reserved for a rhetorical flourish. De la Tour knows that in an argument fatigued by grief, faces migrate toward the truth by millimeters.

The Candle as Theological Device

Unlike the clear oil lamps he often uses in his Magdalene nocturnes, de la Tour gives Job’s wife a stub of tallow candle. It is grasped near the base, the flame barely longer than a thumb-joint. That choice matters. A candle consumed by its own labor is a fitting image for a household burned by loss. The wife wields it like proof. If the light cannot extend beyond the little circle she controls, what good is the God Job won’t abandon? And yet the candle also illuminates Job and the space between them, sustaining the possibility that their exchange itself—honest, hard—may be a form of faith. The candle thus functions as argument both for and against patience, a dialectical flame.

Color Harmony and Emotional Temperature

The palette is austere: the indelible red of the robe; the warm putty of wall and floor; the leathery browns and umbers of shadow; the bone tones of Job’s skin. Within this narrow range, temperature drives emotion. The robe’s red is not jubilant; it is heated intention. The cooler whites of sleeve and headscarf cushion the severity. Job’s skin receives a cooler, almost ashy light, which underscores his depletion without turning him cadaverous. The harmony yields a solemn warmth—enough heat to keep the scene human, little enough to keep it grave.

Space, Silence, and the Chamber of Argument

There is almost no furniture: a block, a wall, a shallow basin on the floor that could be a broken bowl or a chamber pot. The void is deliberate. It pushes the figures close to the picture plane and to one another. Silence thickens the air. We can feel the stillness after a sentence, the soft scrape of bare feet, the guttering of the candle. The room’s poverty resists allegorical inflation. The debate occurs not in a mythic landscape but in the same lean quarters where illness, debt, and heartbreak argue today. De la Tour’s respect for poverty is architectural; the room protects attention.

The Ethics of Seeing and the Viewer’s Position

We stand in the triangle of light, close enough to be addressed, yet no one looks out at us. The painting refuses to enlist us as judges or partisans; it seats us as witnesses. Our job is to hold the scene with a fair gaze, which is precisely the ethic the picture itself practices. De la Tour treats both figures with even dignity. The wife’s impatience is given beauty and weight; Job’s patience is granted muscle rather than vapid piety. The work calls viewers to the kind of seeing that human conflict deserves: steady, exact, unexcited by spectacle.

Relation to De la Tour’s Care Nocturnes

This canvas belongs to the family of de la Tour’s night scenes of care—Saint Sebastian tended by Irene, the Magdalene’s inward vigil, newborns cradled by midwives. What distinguishes “Job Mocked by His Wife” is that care becomes argument. Instead of simple nursing, we meet a marital dispute forged in catastrophe. And yet the same virtues apply: a single domestic light, large planar modeling, hands that carry decisive meaning, and a willingness to grant ordinary people the scale and gravity usually reserved for saints and heroes. De la Tour’s consistent thesis is that attention is sacred. Here, even rebuke is photographed with mercy.

The Body of Job and the Refusal of Sensationalism

Pain painting often indulges in lurid display. De la Tour denies that hunger. He renders Job’s body as a map of strain without open wounds or grotesque dramatics. The biceps hangs narrow; the ribs declare themselves under thin skin; tendons and knuckles speak of work once done and now interrupted. The discipline keeps the viewer from the distraction of horror and fixes attention on the moral center: how a person thinks when everything is gone. In that decision, de la Tour aligns with Job himself, who refuses to make his suffering his only identity.

Marriage, Speech, and the Fragility of Consolation

One reason the picture disturbs is that it dignifies spousal speech that most religious paintings ignore. The wife is not a cipher or prop; she has a voice that has carried the same losses and found different conclusions. She is tired of funerals and the arithmetic of ruin. Her counsel is wrong, the tradition says, but it is credible. The painting lets her be wrong in a human way. It also lets Job answer not with triumph but with attention. The folded hands, the turned head, the bare feet planted on the ground say: I am listening and I will not move. Consolation is fragile; it accepts being argued with.

Technique, Edge, and Plane as Rhetoric

The persuasiveness of the painting lies in what de la Tour chooses to sharpen or soften. The edge of the candle flame is feathery, giving light a living border; the hem of the robe is firm, grounding the wife’s mass; the ridge of Job’s shin is precise, lending the legs a carved truth; the line of his jaw dissolves into beard just before it meets the wife’s shadowed face, preventing the argument from becoming a clash of outlines. Brushwork remains mostly invisible, surfacing only where a little texture carries sense: stipple in the beard, soft drag along the robe’s interior where light rebounds, a slight scumble on the wall to catch glow. Every micro-decision argues for the painting’s fairness.

Theological Stakes Without Preaching

The canvas accommodates multiple readings. A devotional viewer can see the candle as conscience and Job as steadfastness under trial, the wife as the temptation to collapse into resentment. A humanist viewer can see two people negotiating disaster with incompatible temperaments. The painting does not condemn; it arranges. Its theology, if one must name it, is a theology of light shepherded toward conversation. Revelation here is not a heavenly blaze but a stubborn little flame that illuminates enough to keep speaking.

Modern Resonance

The scene feels contemporary because it is; households still face sequences of loss that exhaust the best among us. The painting recognizes how suffering strains speech and how love can sound like mockery when hope and pragmatism part ways. It cautions against reading either spouse as villain. It suggests, with the authority of a candle that keeps burning, that argument within fidelity is itself a kind of endurance. In a world of hot takes and instant verdicts, this nocturne models the slower courage of a listening body and a steady hand.

Comparison with Other Images of Job

Renaissance and Baroque Jobs often kneel amid ruins or cry to heaven under dramatic skies. De la Tour removes the sky and therefore the theater of complaint. He leans on interior severity instead of exterior catastrophe. His Job has no rubble, only a room, a spouse, and a candle. The subtraction is powerful. It brings the story from epic to domestic scale, where most of us conduct our own theologies. In doing so, it also redeems the wife from the margins. She becomes a central participant whose grief has logic even when her counsel falters.

The Quiet of the Floor and the Bare Feet

One of the painting’s most telling details is simply where it meets the ground. Job’s bare feet rest on a floor that shares the candle’s warmth; the wife’s hem barely clears it. The floor returns the light like a low tide of ember, setting the body in a believable world. There is nothing between them and the earth—no carpet, no dais. The theology of this floor is simple and large: whatever is said here, it is said close to dust. The dust is not a threat; it is the medium through which meaning travels.

Conclusion

“Job Mocked by His Wife” condenses a lifetime of questions into one room with one flame. Light is not spectacle but method. Color is reduced to a few solemn chords. Gesture performs the text without pantomime. Faces carry fatigue and force at once. De la Tour makes the scene fair to both participants and faithful to the book’s nerve: the insistence that honest argument belongs inside fidelity. What remains after looking is not a verdict but a way of seeing—steady, architectural, compassionate. The candle keeps burning, and in its narrow weather two people keep speaking. That is the painting’s miracle.