Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

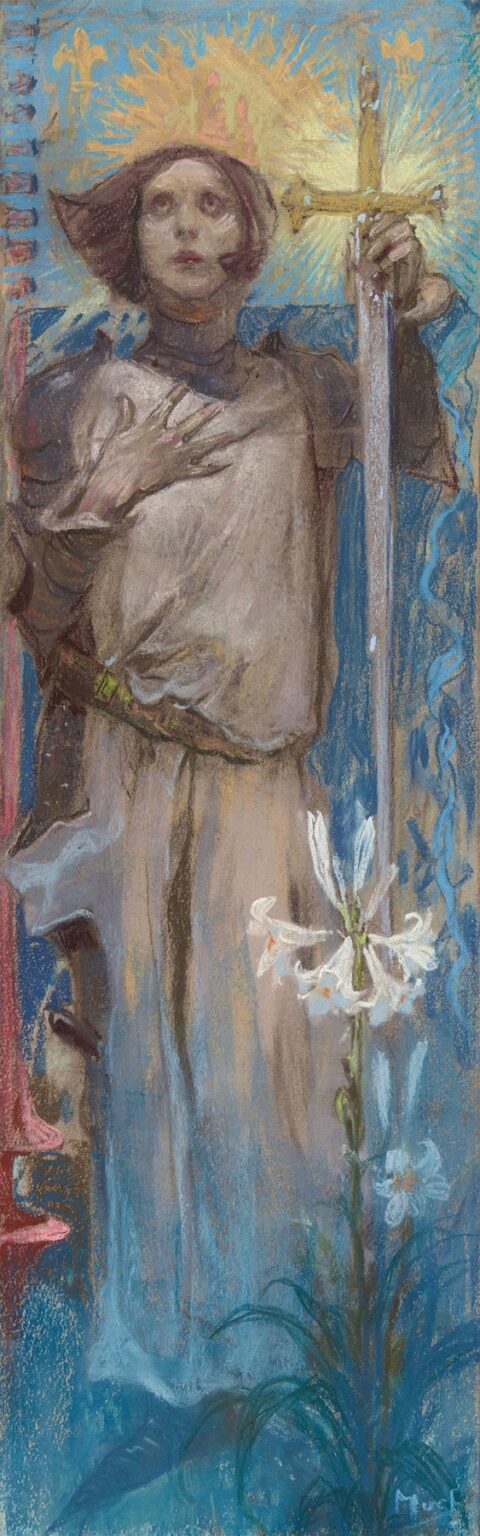

Alphonse Mucha’s “Joan of Arc. Apparition” (1909) compresses revelation into a narrow, luminous field. The image is vertical, almost banner-like, and everything in it climbs: a young warrior-saint in partial armor, a blade that reads simultaneously as sword and cross, a burst of golden light that crowns the figure, and white lilies that rise from the bottom edge like a living candle. Where Mucha’s Art Nouveau posters often flattered the modern city with graceful arabesques, this work turns inward. It stages the instant when an interior voice becomes a public destiny—the moment that medieval chronicles attribute to Joan of Arc’s visions. Rendered in pastel, the piece feels breathed onto the paper: scumbled blues and ochres, quick chalk accents, and a halo that seems to flicker as your gaze moves.

Historical Setting and Why the Subject Fits Mucha

By 1909 Mucha had returned to his homeland and was preparing the monumental cycle later called the Slav Epic, a project rooted in spirituality and national memory. A saint who fused mystical experience with civic courage would have appealed to him on several levels. Joan of Arc offered a template for the artist’s constant preoccupations: how symbols animate communal life, how the sacred can arrive in ordinary rooms, and how a single figure can carry the weight of a people’s hopes. Although Mucha is best known for Parisian lithographs, he was never only a commercial stylist. He was also a symbolist storyteller who used emblem, gesture, and light to cast moral narratives. This image belongs to that deeper stream of his work.

The Chosen Moment: Vision Becoming Vocation

The title names the precise drama: apparition. Mucha shows not a battlefield or triumph but the threshold at which a vision arrests the body. Joan looks up and slightly past us; her left hand presses the tunic at her heart, while the right lifts a vertical blade capped by a gold cross. The face is stunned, not ecstatic—eyes round, lips parted, breath caught—and the body remains modestly grounded in heavy cloth and chain. In this pause between hearing and acting, the viewer sees the vocation take hold. It is a psychological scene, nearly cinematic, and it resists anecdote. There are no angelic figures, no specific church interior, only signs: light, cross, lily, and the unmistakable poise of someone who has just realized a life will change.

Composition: A Sacred Axis in a Banner Format

The composition is a study in vertical alignment. The sword/cross forms the central axis; the saint’s body, the blue field behind, and the stem of lilies below all rise to meet it. A soft red column at left and a wavering blue margin at right act like drapery wings, framing the vision without enclosing it. Mucha anchors the long format with a clear sequence from bottom to top: roots and leaves, blossoms, garment, hands, face, halo, sky. That laddering of motifs guides the eye in an ascent that subtly rehearses Joan’s own movement from earthbound peasant to illuminated messenger. The narrow format matters. It evokes a processional banner or a devotional panel, not a secular poster, and therefore primes the viewer for reverence before the first detail is read.

Light as Theological Argument

Mucha paints light as if it were substance. The golden radiance behind Joan does not merely backlight the figure; it asserts presence. Rays surge outward in short pastel strokes, their irregularity keeping the halo alive. The cross at the sword’s hilt glows the same color as the halo, so it reads not as metal reflecting outside illumination but as an internal source, as if the instrument of faith is itself incandescent. The blue field around the body deepens as it nears the edges and remains lighter behind the head, intensifying the apparition’s center. Between the cool blue and warm gold, a color dialogue unfolds that has long linked sacred art to doctrine: heaven and glory, humility and grace.

Color Vocabulary and Emotional Weather

The palette is concentrated: sky and robe in layered blues; flesh in desaturated peach and ash; armor and belt in silvery brown; light in saffron and pale citron; accents of coral in the lips and left margin. The restricted harmony is not austerity but focus. Blue sets a contemplative temperature; gold interrupts with revelation; muted neutrals keep the vision from submitting to theatrical excess. As a colorist, Mucha knows how to let one note electrify a chord. Here the single brilliant yellow at the cross’s intersection does that job; it’s both the visual climax and the theological thesis.

Pastel Technique and the Felt Surface

Unlike his lithographs with smooth, enamel-like color, Mucha’s pastel registers the touch of the hand. Scumbled passages build atmosphere; broad side-of-the-stick sweeps lay down robe and sky; flicked wrist marks create the halo’s fireworks. He lets the ground breathe through, especially in the robe’s highlights and the blue margins, so the paper becomes a third actor between pigment and light. Edges soften or sharpen according to meaning: the jawline diffuses slightly into the glow, while the fingers that clutch the sword are defined with firmer strokes. This tactility gives the image the vulnerability of a working drawing even as it achieves the authority of an icon.

Gesture and the Body’s Logic

Joan’s left hand on her chest is more than pious convention. Anatomically, it turns the torso a fraction, which angles the head upward and makes the neck lengthen—classic signals of attention and openness. The right hand secures the sword halfway up its length, not at the hilt, as if the instrument were both staff and standard. The elbows pull inward, containing the figure’s energy and heightening the sense that something interior is unfolding. Even the mouth participates: parted, but not speaking, it belongs to a person receiving rather than proclaiming. Mucha choreographs these small decisions so that the body itself narrates.

Iconography Layered Like Vellum

The painting is a primer in symbol. The sword doubles as cross, conjoining militant duty and spiritual authority. The halo declares sanctity but also maps impact—the exact region through which the voice arrives. The lily is the most traditional of Marian emblems, standing for purity; planted at Joan’s feet, it localizes innocence in the landscape of action and hints at sacrifice as the stem tilts toward the blade. Even the faint shapes that decorate the left edge—suggestive of architecture, banners, or escutcheons—whisper the civic arena that will test private conviction. Mucha’s gift is to keep all of this legible without pedantry. Each sign is integrated into the composition’s practical needs: the cross as axis, the lily as counterweight, the halo as illumination.

Between Art Nouveau and Symbolism

The piece inhabits a border between styles. You can still see the Art Nouveau sensibility in the elongated format and in certain arabesques along the margins, but the center is Symbolist in temperament: psychological interior, emblematic objects, and a refusal of descriptive setting. Where his Paris posters accentuated beauty and ornament, this work lets beauty serve meaning. The hair is not opulently spiraled; it is close-cropped to the helmet line. The garments fall in believable weight rather than decorative cascades. Even the lilies, while elegant, are botanically frank. This is the discipline of a mature artist turning his vocabulary toward devotion.

The Humanity of the Face

Much has been written about the saint as emblem. What persists after symbols are counted is the human face. Mucha draws Joan’s features with tender economy: shadowed sockets that widen the gaze, a straight nose, an unornamented mouth, and small areas of warm highlight across the cheekbones. There is no glamour here. The face belongs to a working body. Yet it carries a gravity that prevents the iconography from floating into abstraction. You are meant to believe in this person’s experience. The slightly uneven texture of the pastel around the eyes gives them a tremor, the impression of moisture or of a look that has just altered. It is a quiet miracle of draftsmanship.

Spatial Ambiguity as Spiritual Space

The background resists place-making. A blue field could be sky, cloth, or the emptiness of a chapel wall; a red vertical on the left could be column, banner, or the trace of a tapestry. Rather than fix a locale, Mucha constructs spiritual space—room enough to stage an encounter, spare enough to keep our attention on its effects. The lack of distinct architecture also keeps the work portable in meaning. Joan could be in Domrémy or in any room where a sudden knowledge breaks in. This portability is one reason images of the saint continue to resonate beyond their historical moment.

Soundless Drama and the Direction of the Gaze

Mucha controls where we look and how quickly. The lilies pull us up into the robe; the left hand arrests us at the heart; the diagonal of the right forearm slides our attention to the blade, which launches us along the long axis into the cross and the burst of gold. Only then do we meet the face, which looks past us—as if borrowing our eyes to look further still. It is a soundless drama built of sight-lines rather than narrative incident. This is how a painter makes an apparition out of marks: by choreographing a path that recreates discovery.

Ethical Tension: Saint and Soldier

No subject better captures the paradox of holiness and force. Mucha does not hide the metal at the throat nor the belt around the waist, but he allows cloth and flesh to be the dominant surfaces. The instrument of violence is also the sign of salvation. The hand that would wield it now only steadies it. The work refuses to resolve this tension; it offers instead a model of consecrated strength—a theme that surely interested an artist preoccupied with the identities of nations and the responsibilities of power.

Materials, Scale, and Intimacy

Pastel on paper is an intimate medium. It invites proximity and registers breath. The medium’s fragility suits the subject’s nonfinal state: an apparition is not yet history; it is a volatile influence. The thinness of pigment on paper allows light to bounce through the color in a way oil often cannot, which is why the halo here seems to bloom rather than sit. Even at modest size, the sheet feels monumental because of its vertical thrust and the concentrated iconography. You do not need a cathedral wall; the paper becomes a portable shrine.

Dialogue with Mucha’s Broader Practice

If you place this piece beside Mucha’s decorative panels or his theater portraits, the continuity appears in the circular burst behind the head (a device he loved), in the strong silhouette against a simplified ground, and in the use of a long vertical to dignify a single figure. What’s different is the austerity and the inward pressure. The ornament that once celebrated perfume bottles and actresses now surrounds a claim on conscience. In that sense, the work anticipates the moral atmosphere of the Slav Epic, where emblem and history meet on equally charged terms.

How the Image Reads Today

Modern audiences may not arrive with medieval hagiography at hand, yet the scene’s emotional grammar remains eloquent. The hand to chest reads as truth felt; the upward gaze reads as attention to something beyond the self; the cross-sword reads as a responsibility accepted. The flower at the base, tender and temporary, invites care. You do not need to share Joan’s theology to recognize the image of someone called to act and frightened by the knowledge. That recognition is why the piece continues to move viewers outside of any particular religious context.

Conclusion

“Joan of Arc. Apparition” is a compact revelation. It gathers Mucha’s talents—command of line, exact feel for symbolic objects, gift for architectural composition, and sensitivity to light—and turns them toward a moment when an interior voice becomes a public path. The work stands comfortably alongside the artist’s most famous posters while pointing to the spiritual ambition of his later years. Its force lies in restraint: a handful of colors, a few signs, and a body sincerely observed. Out of these, Mucha builds not a pageant but a visitation. Stand before it and you feel the silence compress. Then the gold arrives, the sword steadies, and the lily rises. The rest—history, trial, memory—is implied. What is shown is the birth of courage.