Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Rembrandt’s “Jesus Christ’s Body Carried to the Tomb” (1645)

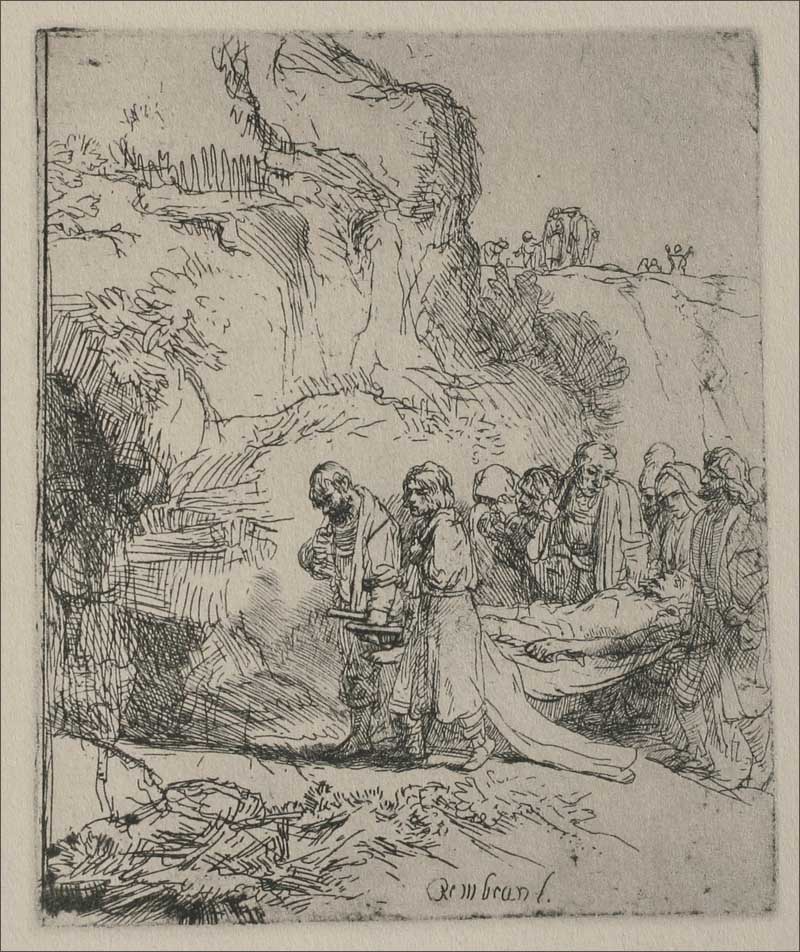

Rembrandt’s “Jesus Christ’s Body Carried to the Tomb,” created in 1645, is a compact masterwork of narrative solemnity and graphic invention. Although intimate in size, the print delivers the gravity of the Entombment with an economy that only a supreme draftsman could command. Rather than staging the scene in a choreographed tableau, Rembrandt casts the moment as a moving procession winding through rocky terrain toward the mouth of a cave. The result is not a fixed icon but a passage of time captured in lines that feel as alive as breath. It is an image about bearing weight—spiritual, physical, communal—and about how the landscape itself seems to acknowledge that weight.

The Procession as Living Sentence

The composition reads from right to left, contrary to the eye’s usual habit, which obliges viewers to adjust their pace to the mourners’ progress. Figures cluster around the shrouded body, bending and straining as they carry Christ toward the tomb. Each participant contributes a clause to the visual sentence: a man presses a cloth to his face, another steadies the bier, women trail behind with hands to their cheeks. The staggered spacing of feet, hems, and shoulders builds a rhythm of grief that is measured but unstoppable. The image therefore functions less as a single picture than as a phrase unfolding, with the tomb as its period.

Landscape as Witness and Theater

Rembrandt frames the procession against a rugged escarpment that swells to occupy the entire upper left. The rock face is scored with diagonal hatchings and wiry contours that echo the direction of movement while also resisting it. The natural world does not yield easily; it must be entered, and the mouth of the cave becomes a solemn aperture where history presses against geology. On the far ridge, small figures silhouette themselves against the sky—observers reduced to punctuation at the edge of the sentence. Their presence enlarges the spatial field and suggests that the Passion has left a rumor abroad in the land, reaching beyond the immediate circle of mourners.

The Cave Mouth and the Architecture of Absence

The cave’s darkness is not filled; it is a deliberate vacancy that swallows detail. This aperture concentrates meaning like an altar. The mourners approach, and the whole drawing seems to inhale. In Christian narrative, the tomb is both destination and threshold, a place where the logic of death will be contradicted. Rembrandt leaves the interior unarticulated so that it may serve as a negative form charged with anticipation. The emptiness is eloquent because it allows the viewer’s imagination to enter before the body does, rehearsing the miracle that will reverse the apparent finality of the scene.

Line as Weight, Line as Mercy

Etching favors decisiveness, and Rembrandt uses the medium’s incisive line to model pressure and release. Heavy cross-hatching under the bier yields a raft of shadow that visually supports the corpse. Softer, broken strokes describe the folds of garments and the textures of hair and beard. Where grief quiets into contemplation, as in the bowed heads and clasped hands, the line thins and loosens. The eye senses weight where lines accumulate and feels mercy where they open. Such modulation turns drawing into dramaturgy, allowing the print to move between burden and blessing without resorting to theatrical gestures.

The Shrouded Body and the Ethics of Depiction

Christ’s body, wrapped and borne at hip height, is presented with reverent restraint. There is no display of wounds or anatomical bravura. Rembrandt chooses ethical understatement, which makes the figure both more credible and more venerable. The shroud’s smooth continuity contrasts with the broken rhythms of the carriers’ garments, concentrating attention without sensationalism. This modesty is theologically apt; the image is about the community’s labor of love, not the spectacle of death. The dignity accorded the body instructs the viewer in how to look.

Faces in Degrees of Grief

Rembrandt’s genius for character emerges in the small orchestra of expressions ranged along the procession. The man at the front presses a cloth to his face in private lament; another glances inward, lips pressed, as if measuring the weight of responsibility; a third looks back toward the followers, conducting the procession’s pace with a turn of the head. None of these faces is heroicized, yet each is distinct. Together they form a spectrum from shocked sorrow to steady duty. The print argues that grief is not one thing but many, and that a community holds them all at once.

Space, Scale, and the Intimacy of the Small

The print’s modest size forces a tactile closeness that painting often disperses. You lean in, and the procession unfolds at the scale of the hand. This intimacy lends authority to the scene’s realism. Boots meet ground with believable friction, hems brush the earth, hands grip the shroud. The smallness is not a limitation but a discipline that concentrates feeling. Rembrandt uses scale to turn a cosmic narrative into a humanly sized task: carry, step, breathe, continue.

The Printmaker’s Craft: Needle, Acid, and Plate Tone

As an etcher, Rembrandt drew into a wax ground on a copper plate, which was then bitten in acid to incise the lines. In this work, he likely combined etched contours with touches of drypoint, whose burr raises a velvet softness along certain edges. The biting varies in depth, producing a hierarchy of line weights that function like tonal values. When printed, a trace of ink left on the plate can produce a faint atmospheric veil, sometimes called plate tone. Even when this veil is light, the drawing breathes with air rather than sitting starkly on the page. The craft is thus inseparable from the image’s compassion; the very means of inscription become analogues for touch.

Rhythm, Pause, and the Logic of Steps

Every procession is a sequence of steps, and Rembrandt makes that logic visible. Note the alternating placement of feet along a shallow diagonal, the compression of bodies as they navigate the narrow path, the way the shroud droops between hands like a suspended syllable. The rock wall introduces a pause, a visive caesura before the final approach to the tomb. Such pacing encourages meditative viewing. You do not scan the image; you keep time with it, and in keeping time you begin to feel the work of mourning as a practice carried by bodies in concert.

The Crowd at the Horizon and the Public Afterlife of Sorrow

The small cluster of figures on the ridge functions as a distant chorus. Some gesture toward the procession; others stand as mute witnesses. Their scale compresses them into signs, but their inclusion changes the meaning of the scene. Grief does not remain private. It spreads through rumor and memory, through those who saw and those who heard. The Passion narrative always contains both intimate care and public consequence. Rembrandt balances them by giving the horizon a voice that is soft yet present.

Theology in the Grain of the World

The rocky terrain is more than setting; it is the world made resistant and real. The Passion does not occur on a stage set built for piety. It unfolds in a geology that has its own logic and indifference. Yet the contours of the rock bend slightly to the procession’s path, acknowledging the passage without surrendering character. In this subtle reciprocity the print suggests that salvation history takes hold in the grain of the ordinary world, not apart from it. The divine drama engages the stubborn materials of time and place.

Dialogue with Rembrandt’s Painted Entombments

When set beside Rembrandt’s painted treatments of the Entombment and Deposition, the 1645 print reveals a parallel strategy rendered with fewer tools. The paintings use chiaroscuro and color to create volume; the print relies on intervals of line. Yet the psychological emphasis is consistent. Rembrandt favors the effort of the bearers, the fold and drag of cloth, the human coordination that dignifies the dead. The etching, by shedding the glamour of paint, approaches the austerity of Scripture itself, which often narrates immense events in spare sentences.

The Viewer’s Place in the Procession

The vantage grants the viewer a position slightly ahead of the party, almost at the threshold of the cave. We are both witness and welcoming committee, receiving the burden that is being carried. This placement complicates the typical devotional stance. We do not merely observe; we feel responsible. The body approaches, and the drawing invites us to make room. In this way the print activates a contemplative ethics: to contemplate is to consent to share weight.

Time, Memory, and the Promise Folded into a Shroud

Although the print narrates burial, it carries the seed of reversal. The shroud that conceals the body reads as a promise folded into cloth. The cave’s darkness, far from final, is a chamber where time will be kept. Lines accumulate like hours, and space holds its breath. Rembrandt does not illustrate the Resurrection; he allows the Entombment to hold its opposite within it, as Christian tradition understands it to do. The mood is not triumphal, yet neither is it despairing. It is the discipline of carrying what must be carried until morning comes.

The Moral Temperature of Rembrandt’s Line

Viewers often remark on the “humanity” of Rembrandt’s art, a word that risks vagueness until one sees how his lines behave. They refuse spectacle and favor persuasion. They admit irregularities and welcome the rough. They countenance sorrow without indulging in melodrama. In this print, the moral temperature is set by the willingness to show labor—the labor of hands, of steps, of communal coordination. Such an ethic of depiction does not merely ornament the story; it embodies its teaching about love that bears all things.

Reception and Contemporary Resonance

Modern eyes, shaped by photography, may be surprised by how cinematic this small etching feels. The procession advances across a believable terrain, motion is implied, and the framing is precise. Yet the image is more than proto-cinematic. It requires the viewer’s slow attention, the kind that allows the etched line to become breath and the white paper to become space. In a culture that often hurries past grief, the print’s measured pace is itself counsel. It teaches that mourning is an action undertaken together and that the dignity of the dead depends in part on the care with which the living proceed.

Conclusion: Bearing, Entering, Awaiting

“Jesus Christ’s Body Carried to the Tomb” is a masterclass in narrative compassion. The procession bears the body with unhurried gravity, enters a landscape that both resists and receives, and approaches a darkness that is charged with promise. Everything essential is present and nothing superfluous. The print converts line into liturgy, inviting us to join the bearers in their careful work. In the hush between the last step and the threshold, we sense the paradox at the heart of the Passion: that the path of love passes through the tomb and that the discipline of carrying will, in time, be answered by the discipline of rising.