Image source: artvee.com

A first look at intimacy and poise

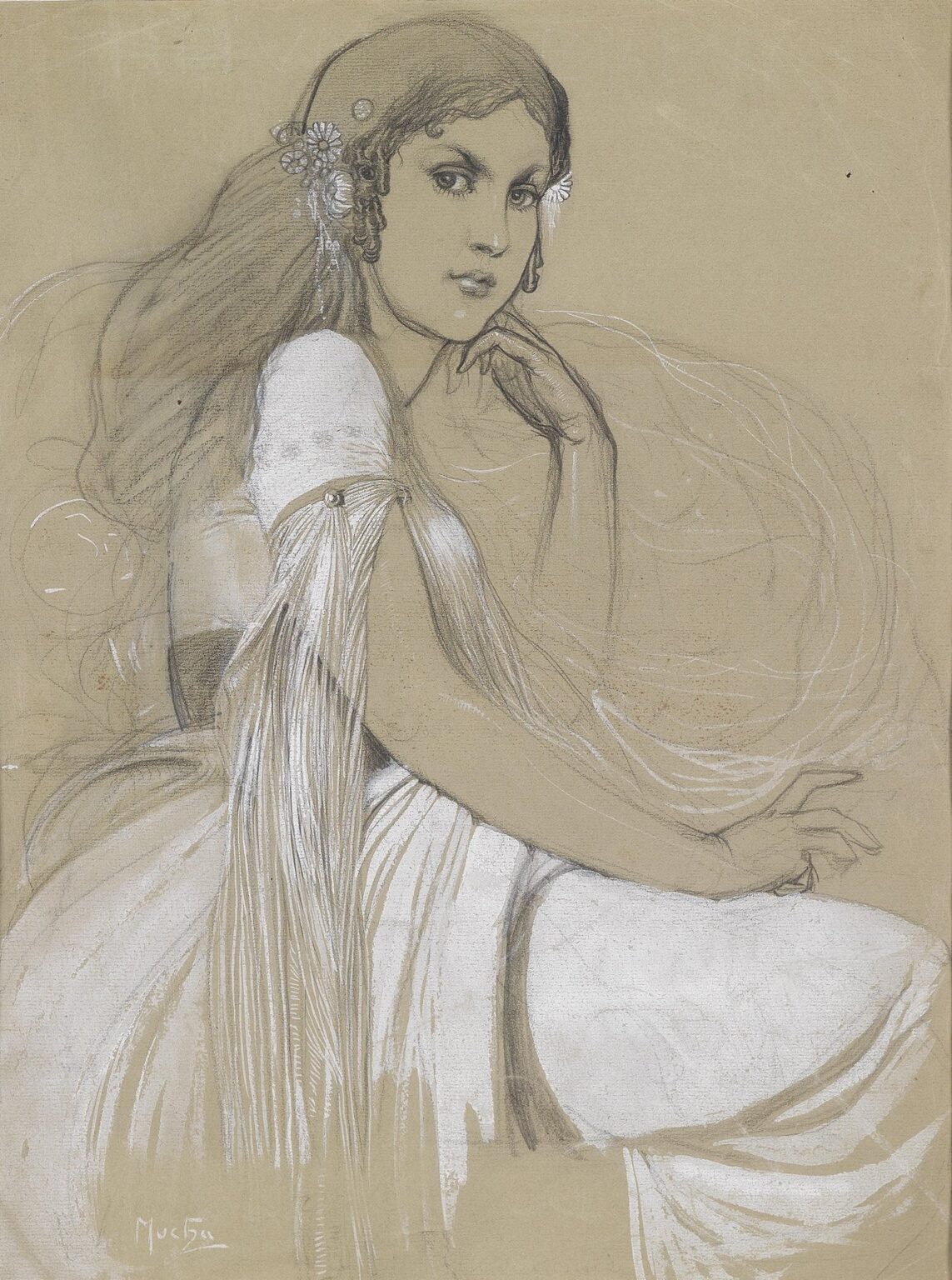

“Jaroslava Muchová” (1920) offers an unusually intimate encounter with Alphonse Mucha’s art. Instead of the monumental allegories or the dazzling color lithographs that made him famous across fin-de-siècle Paris, we meet a quiet drawing on toned paper. A young woman, seated in three-quarter profile, turns her head to meet the viewer’s gaze. Her elbow rests lightly as the fingers of one hand touch her chin, while the other hand hovers, poised to complete a graceful arc. Long hair streams behind her in airy, swirling lines. The dress is luminous, modeled with broad passages of white heightening that catch the light like silk. The result is both portrait and emblem, personal likeness and archetype.

Who Jaroslava was and why she mattered to Mucha

Jaroslava Muchová was the artist’s daughter and one of his most constant muses. She grew up in the studio, surrounded by canvases, props, embroidered textiles, and the ritual rhythms of large-scale projects. She modeled for allegorical female figures and later became an artist and custodian of her father’s legacy. Knowing this relationship changes how we read the drawing. The picture is not merely a beautiful head and figure; it is a record of familial trust. Mucha’s women in posters often embody impersonal ideals—Seasons, Arts, or star actresses—yet here the ideal and the individual fuse. Jaroslava’s presence allows the artist to humanize the archetype he helped invent.

1920 and the new phase of Mucha’s career

The year 1920 sits squarely within Mucha’s late period, when he was absorbed by national projects in the newly formed Czechoslovakia and working on the cycle known as the Slav Epic. His studio practice at this time oscillated between vast narrative canvases and smaller drawings that clarified faces, costumes, and gestures. The portrait’s mixture of decisively finished passages and exploratory lines matches that rhythm. It feels like a private pause in the midst of public ambitions—a work made to keep the hand supple and the eye alert, and perhaps to secure a likeness that could inform later allegorical figures.

Composition built from curves and counter-curves

Mucha organizes the sheet with a choreography of arcs. The sitter’s back, forearm, and thigh create a long S-curve that anchors the composition; the soft oval of the head turns gently against it; and the hair unfurls in concentric sweeps that echo but never duplicate the primary movement. These counter-curves produce the sensation of breath within a still image. He tucks the figure into the lower left quadrant and lets the hair occupy the right half of the sheet, balancing mass against air. The composition demonstrates a perennial Mucha principle: line creates architecture before any color or texture arrives.

The face, gaze, and psychology of attention

The head is the most completely resolved area. Eyebrows are delicately arched; the eyelids are defined with a few confident strokes; the pupils are shaded to anchor the gaze. Mucha places the irises slightly toward the viewer’s left, so the eyes meet ours without staring. The mouth is shaped softly, neither smiling nor severe, and a light shadow under the lower lip grounds the features. That subtlety is crucial. It avoids theatrical emotion and replaces it with a poised alertness, the sort of look one gets in conversation when truly listening. Even when Mucha idealizes, he allows the personality to breathe.

Hair as atmosphere and emblem

The hair, threaded with small daisies or similar blossoms, is both material and metaphor. With the tip of a dark pencil, Mucha maps the main strands; with soft rubbing he creates mass; and with bright white he teases out high lights along select filaments. As the locks stream to the right, they dissolve into spirals and nearly abstract coils, turning hair into atmosphere. This is the Art Nouveau arabesque at its most tender—decorative yet obedient to the subject. The tiny flowers tucked near the ear crown the sitter without pomp, suggesting freshness and youth rather than pageantry.

Drapery incandescent with white heightening

One of the drawing’s chief pleasures is the way the dress glows. Mucha selects a mid-tone paper and then paints or rubs broad areas of opaque white to model the cloth. Over that light ground he draws with graphite or charcoal, so contours remain crisp but volumes feel soft. Notice the cascading tassels that hang from the shoulder clasp: every strand is pulled with a swift vertical flick, together reading as silk threads catching light. The kneecap, the sleeve, and the folds at the waist are handled differently—wide, cloudy swathes for broad planes; fine hatching and accents for edges. Mucha’s knowledge of fabric is not specifically descriptive; it is kinetic. You can predict, from the marks alone, how the cloth would move if the sitter inhaled.

The role of toned paper and economy of means

Working on warm, toned paper lets the artist skip large zones of modeling. Mid-tone equals shadow, white equals highlight, and the untouched paper becomes skin lit from within. This system produces a luminous economy. Rather than build every value from scratch, Mucha orchestrates a duet between the paper’s color and the layered media. The paper also harmonizes the drawing: hair, skin, and background share a common warmth that binds all parts even when line quality varies.

Hands as structural punctuation

The hands deserve special attention. The nearer hand props the chin, the index finger making a small triangle that locks the face into the body’s long curve. The farther hand hovers, fingers slightly spread, as if about to trace a shape in the air. Mucha understands that hands transmit character; he lets them be elegant but not mannered, articulate yet relaxed. They punctuate the drawing like commas, slowing the tempo just enough for the eye to rest before moving along the lines of hair and cloth.

Ornament that grows from structure

Ornament in this portrait is not stuck on; it grows from the figure’s anatomy and the garment’s construction. The small shoulder clasp, with two tiny studs, becomes a hinge from which the tassels fall. The flower accents gather where the hair would naturally hold them. Even the faint, looping circles in the background follow the direction of hair and shoulder lines. This is Mucha’s organicism at work: decoration as anatomy’s echo.

From likeness to archetype: classical echoes

Though unmistakably a portrait, the drawing glances toward antiquity. The pose recalls seated figures on classical reliefs; the garment evokes Greco-Roman drapery; the hairstyle with floral accents suggests a nymph or muse. Mucha often employed antiquity as a vocabulary of poise and virtue. By giving Jaroslava this timeless frame, he elevates the familial to the universal, proposing her as a modern embodiment of grace. Yet the face resists the coldness of a statue. The soft shading around the eyes and mouth preserves a sense of lived time.

Process on view: finished and unfinished in dialogue

Look closely and you see decisions left visible. There are light circular guidelines near the upper left of the torso; strands of hair on the right evaporate into suggestion; the lower portion of the dress is more loosely indicated than the glowing sleeve. These variations are not flaws; they stage a conversation between the finished and the pending. Mucha, whose printed posters had to be perfectly resolved, relishes the freedom to let a line remain exploratory. The viewer is invited into the studio, to follow the hand’s path and the eye’s priorities.

Comparison with the famous posters without repeating them

Mucha’s most iconic lithographs depend on decorative frames, radiating halos, and text panels. Here, none of those devices appears, yet the underlying grammar remains. The figure anchors the page with an unmistakable silhouette; the hair acts as an ornamental field; and a rhythmic border is implied by the way the lines swell and retreat near the edges. The portrait therefore feels unmistakably “Mucha” while allowing a gentler, more private register.

Light, volume, and the sculptural approach to drawing

Mucha thinks like a sculptor when modeling faces and arms. He sets planes with broad, simple tones, then turns edges with a few decisive accents. The cheekbone receives just enough shadow to roll into the temple; the upper arm brightens boldly and then melts into half-tone before the elbow’s notch. This kind of modeling requires confidence; one misplaced dark would stiffen the skin. Instead, the volumes feel supple, more like clay smoothed by the palm than like laborious shading.

National currents and the Slav Epic in the background

Although the drawing is not overtly “national,” it was made during years saturated with historical storytelling. Mucha was painting scenes of Slavic myth and history, peopled with heroines and personifications. Jaroslava, appearing here as herself, nevertheless carries a whisper of those figures: the vigil, the inward strength, the sense that beauty is allied to dignity rather than vanity. The portrait reads like the everyday counterpart to the epic—an embodiment of the cultural future those giant canvases celebrated.

The emotional climate: serenity charged with alertness

The portrait’s mood is calm without losing vitality. The sitter’s gaze engages, but the body rests; the dress glows, but the background remains quiet; hair flies out, yet hands gather inward. This balance keeps the drawing from slipping into reverie or stiffness. You sense that the moment could shift—a small smile, a question, the sweep of a hand—and the whole arrangement would rearrange. In other words, the image is alive.

Materials and the sound of the mark

Part of the drawing’s pleasure comes from how clearly you can “hear” its making. Lines scratch with graphite crispness; soft areas whisper where the medium is rubbed; white heightening sits slightly raised and catches the light. That audible materiality keeps the portrait intimate. Nothing here pretends to be more than paper, pencil, and white; yet those humble elements, guided by a sure hand, create richness more persuasive than any lavish pigment.

From child muse to collaborator and guardian

The picture also foreshadows Jaroslava’s long role in preserving and interpreting her father’s art. As she matured, she painted, assisted, and later tended the large canvases, ensuring that the works survived war, storage, and travel. The portrait therefore carries an intergenerational story: the artist invests art in his child; the child later invests care in the artist’s art. It is a human cycle sealed here by a gaze that seems both trusting and already responsible.

Why the portrait feels contemporary

Viewers accustomed to digital images can still feel the immediacy of this sheet. The pared palette, the graphic clarity, and the combination of graphic edge with atmospheric blur all align with present tastes in illustration and fashion drawing. The figure’s direct gaze also resonates with contemporary portraiture’s preference for authentic presence over theatricality. What looks “classic Mucha” remains current because it treats design as a living language rather than as ornament alone.

Lessons for artists and designers today

Several practical insights radiate from the drawing. Start with a clear silhouette; it carries the mood before details do. Use toned paper to let middle values do the heavy lifting, reserving white for decisive highlights. Allow ornament to sprout from structural points—the clamp on a shoulder, the logic of a seam—so decoration becomes anatomy’s ally. Keep varying line weight to direct attention without shouting. Above all, let the face set the emotional temperature and let everything else harmonize around it.

A closing reflection on tenderness and craft

“Jaroslava Muchová” is an exercise in tenderness disciplined by craft. Every stroke honors likeness, yet every passage contributes to a larger orchestration of line and light. The drawing shows a master near the end of his career returning to the simplest means and finding in them inexhaustible nuance. It also shows a father looking at a daughter and, in the space of a sheet of paper, giving her the dignity of myth without stealing from her the freshness of youth. That combination—personal love and professional clarity—is what makes the portrait linger in the mind long after its last gleam of white has faded from view.