Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

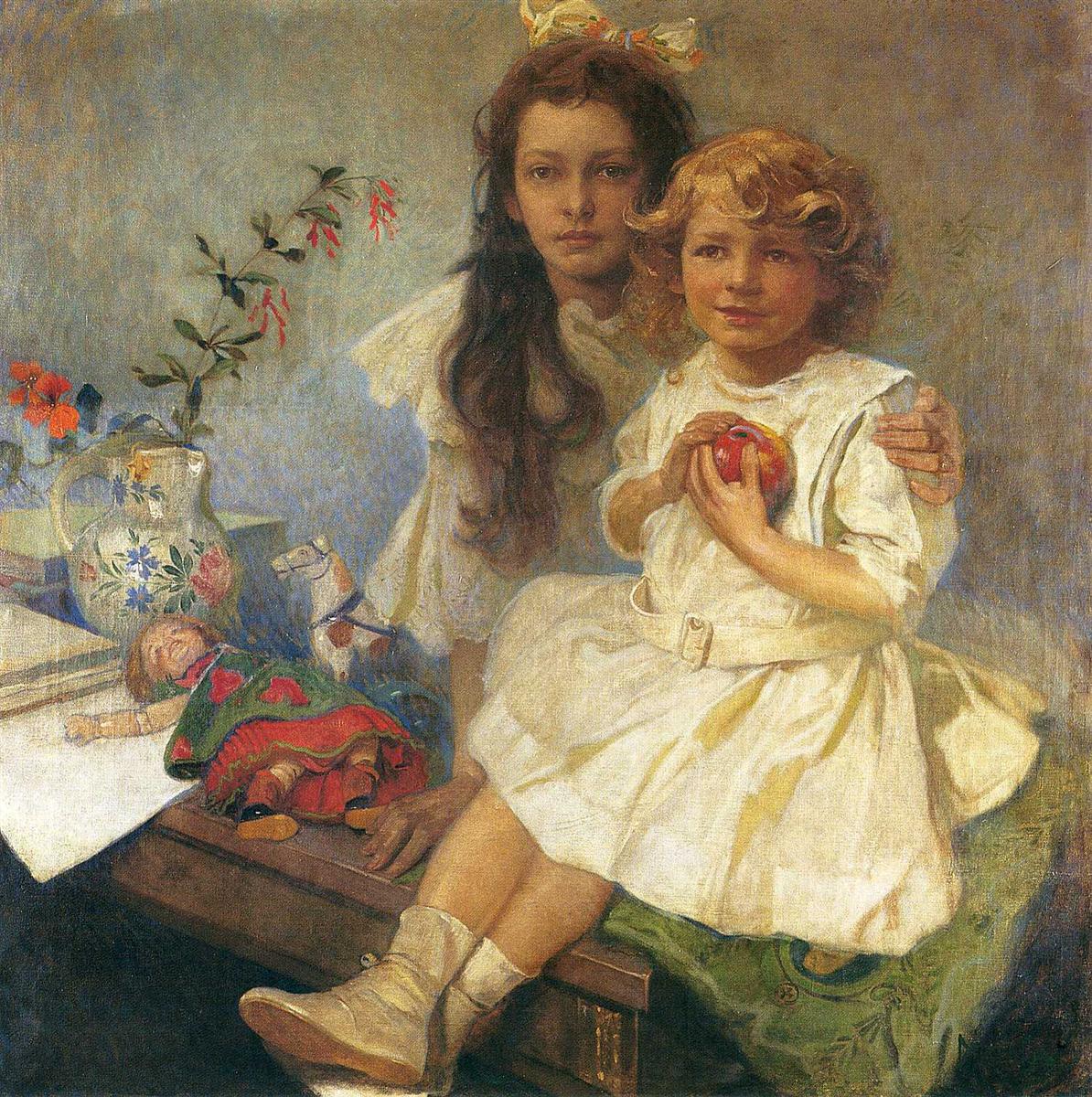

Alphonse Mucha’s “Jaroslava and Jiří, the Artist’s Children” (1919) is a radiant counterpoint to the heroic scale of The Slav Epic he had just completed. Where those canvases address history in the plural, this painting attends to the singular rhythms of home. Two children sit close on a studio bench: Jaroslava, the elder daughter with dark hair and a pale bow, steadies her younger brother Jiří, whose sunlit curls halo his head as he cradles a red apple. Around them a little world of toys and flowers gathers like a chorus—a painted pitcher, a doll in folk dress, a small wooden horse. The palette is warm and domestic, the light gentle, the touch tender. It is a family portrait that doubles as a meditation on continuity after war and upheaval.

Historical Moment and the Artist’s Intention

The year 1919 was a hinge for Mucha and for his newly independent country. Czechoslovakia had been declared a year earlier; The Slav Epic had begun to appear in public; and the artist, long associated with Parisian posters, had returned decisively to his homeland. Painting his own children at this moment was more than private pleasure. Jaroslava (born 1909) and Jiří (born 1915) represented a generation that would inherit the cultural labor their father had shouldered. Jaroslava would become a painter and later steward of the Epic; Jiří would grow into a writer and chronicler of his father’s life. The portrait anticipates those futures without leaving childhood. It is at once intimate record and quiet civic hope.

Composition and the Architecture of Closeness

Mucha builds the picture around a subtle triangular armature. Jiří’s white dress forms the bright apex at right; Jaroslava’s darker head anchors the upper center; their legs and the bench create the base. This triangle communicates stability and intimacy: the children lean toward one another, and the viewer feels invited to draw nearer. At the left, a still-life ledge pulls the eye into a secondary, rectangular stage of pitcher, book, and doll. The push-pull between these zones—human triangle and still-life rectangle—animates the space without disturbing its calm. Everything flows back to the children, in part because Jaroslava’s arm encircles her brother and visually completes the triangle with a human line.

Gaze and Gesture as Narrative

The story of the picture is told in the quiet exchange of looks and hands. Jaroslava gazes outward with composed seriousness; she is the painting’s guardian, the older sibling already practicing watchfulness. Jiří looks a little to the side, shyly confident, as if listening to someone just beyond the frame. Both bodies incline forward. Jaroslava’s hand rests across Jiří’s shoulder, the classic protective gesture; his hands close around the apple with ceremonial care. These small choices replace theatrical plot with the drama of trust. The painting feels like a pause in play, the moment a child is asked to sit still and the other chooses to help.

Symbolism of the Apple, Toys, and Flowers

Objects in Mucha’s domestic theater are never mere props. The apple glows as a compact symbol with several registers: childhood nourishment, knowledge waiting to be tasted, and a coin of exchange between siblings and generations. The doll wears a stylized folk costume, knitting the world of play to the artist’s lifelong devotion to Slavic ornament and story. The wooden horse evokes mobility and imagination, a toy that promises travel while the child remains safely seated. The porcelain pitcher with floral sprays, set beside real blossoms in a glass, rhymes painted nature with living stems, a subtle salute to the partnership between craft and life that sustained Mucha’s art. Together these things speak of a household where culture is not simply displayed but handled by small hands.

Palette and the Warm Intelligence of Light

Mucha modulates a palette of creams, soft ochers, moss greens, and muted blues so that the children’s faces and white clothing become sources of light. Jiří’s curls catch amber notes; Jaroslava’s dark hair absorbs and reflects cooler tones; the apple contributes the only decisive red, anchoring the chromatic composition without shouting. Light gathers from the left, skimming the pitcher and the doll before settling on the children’s cheeks. Shadows are warm, transparent, and brush-laid rather than hard-edged. The effect is a room whose air seems stirred by recent conversation, not by studio lamps. The painting glows as if lit by a patient afternoon.

Drawing, Edges, and the Discipline Beneath Tenderness

Although the surface is painterly, Mucha’s draftsmanship quietly governs the scene. Edges thicken where weight collects—at the bend of an elbow, along the bench’s lip—and taper where forms soften into light—around Jiří’s cheek and Jaroslava’s bow. The arabesque of hair, a signature of his poster work, relaxes into natural strands that still retain rhythmic clarity. The still-life objects are described economically, with just enough contour to hold their place while the children remain the focus. This balance between soft modeling and decisive line keeps sentiment from sliding into sweetness.

Textures, Fabrics, and the Sensation of Touch

The painter’s hand delights in fabric. The children’s white dresses are not flat fields but constellations of subtle temperatures—ivory at a fold, cooler linen at the sleeve, a warm glaze at a knee. Jaroslava’s bow feathers into light; Jiří’s socks and shoes are handled with the loving accuracy of a parent familiar with tiny buckles. The tablecloth under the doll bears patterned edges, while the green drape under the seated boy murmurs with ornamental motifs. Viewers can almost feel the crispness of starch, the weight of the apple, the cool enamel of the pitcher. Such tactile intimacy is a virtue of portraiture that posters cannot easily deliver; here it forms the backbone of affection.

Space, Depth, and the Studio as Home

The background plane is a breathable neutrality, a blue-gray field mottled by subtle brushwork that suggests but does not insist on a wall. Books and the pitcher create a shallow wedge of recession, and the toy horse adds a middle-distance note that keeps the scene from feeling cramped. This domestic depth locates the children not in an abstract studio void but in a working room—shelves within reach, a surface for drawing or reading, a place where adults and children share space. In that sense the painting is an architectural portrait of Mucha’s household values.

From Poster Icon to Living Child

For many viewers, Mucha’s reputation rests on the idealized women of his Art Nouveau posters—faces framed by haloes of hair and ornament, bodies clothed in symbolic draperies. This painting translates that vocabulary into the register of the lived. The arch of Jaroslava’s bow remembers the curves of those haloes; the patterned green drape whispers of decorative borders; but the children’s faces are particular, unrepeatable. The image proves that the compositional intelligence behind his most famous prints could serve observation as well as allegory. Where the posters advertise desire, this portrait observes attention.

Psychological Presence and the Afterlife of War

The serenity of the scene does not erase the date. Painted a year after the end of the First World War, it feels like a benediction over a threatened childhood. Jaroslava’s grave gaze and Jiří’s careful grip on the apple read as small acts of resolve. The portrait acknowledges fragility while giving form to resilience—the calm concentration in which families rebuild. This is not a public allegory of nationhood, yet it does what good private pictures always do: it makes the future imaginable by honoring the present.

The Role of Jaroslava and Jiří Beyond the Picture

Knowing the later lives of the sitters enriches the painting’s resonance. Jaroslava would assist her father on restorations and champion The Slav Epic’s care; Jiří would become a writer and, after wartime imprisonment, a voice for his father’s legacy. This retrospective knowledge folds back into the apple, the book, the doll: tokens of seeds that did indeed grow. Even without that history, the portrait communicates the dynamic: an older child already carrying responsibility, a younger one held and encouraged. The painting reads as a pledge—of nurture given now and strength expected later.

Rhythm, Repetition, and the Music of Detail

Mucha organizes small repeats into a visual melody. White recurs across dresses, socks, papers, and the doll’s blouse; red echoes between apple and doll’s skirt; floral motifs chime between pitcher and real stems; curves answer curves from bow to apple to horse’s neck. These rhymes guide the eye in gentle loops that always return to the children’s faces. The musicality is never mechanical. It is the kind of order one senses in a tidy room where play has paused but not ended.

Technique and the Breath of the Surface

The paint handling feels both layered and immediate. Thin scumbles veil earlier tones, especially in the background; opaque touches describe highlights on ceramic and skin; semi-transparent glazes warm shadowed folds. The result is a matte glow akin to fresco, a surface that absorbs light rather than throwing it back. This suits the subject: family intimacy wants a softness that rewards long looking. The canvas reads well at distance—two bright dresses, a small stage of toys—but repays proximity with brushstrokes that record the tempo of the painter’s care.

The Ethics of Portrayal

A portrait of children always risks adult sentimentality. Mucha avoids it by granting his sitters moral presence. Faces are not pushed into sweetness; they are left with their own equilibrium. Jaroslava’s gaze meets the viewer as a peer; Jiří’s sideways look is curious, not coy. The painter’s affection is legible in the hand on a shoulder and the craft lavished on small shoes, but he does not manipulate. He witnesses. That ethical steadiness is the painting’s abiding grace.

Why the Picture Endures

“Jaroslava and Jiří, the Artist’s Children” endures because it reconciles textures of life that are difficult to hold together: private love and public hope, delicate detail and structural clarity, the stillness of a pose and the liveliness of objects waiting to be played with. It reminds viewers that the foundations of culture are laid in rooms where siblings sit close, where a pitcher of flowers shares a table with a doll, where an apple is held as if full of meanings. After the storms of the 1910s, Mucha answers with a small, luminous thesis: the future begins at a bench where attention ripens into care.