Image source: wikiart.org

A First Glance at a Luminous Character

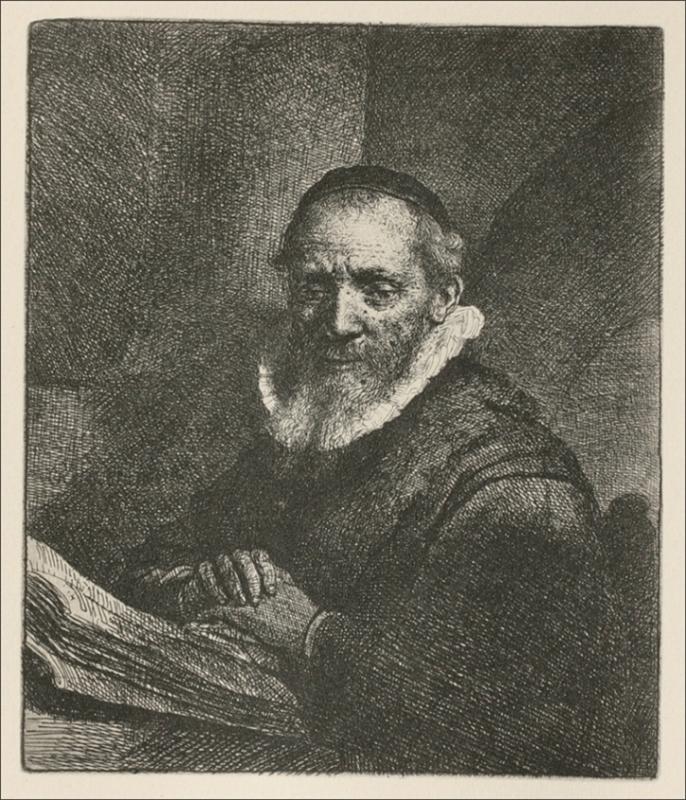

Rembrandt’s 1634 likeness of Jan Cornelis Sylvius draws you in with the steady warmth of a human presence discovered in half-shadow. The sitter turns slightly toward us, his beard picked out by light, his eyes glinting with intelligence and kindness. Hands interlace before an open book that anchors the foreground. Though small in scale, the print feels expansive; every grain of light seems to carry breath. This is not a rigid emblem of status but a conversation begun—quiet, attentive, humane.

The Man Behind the Image

Jan Cornelis Sylvius was a respected preacher in Amsterdam and a relative by marriage to Rembrandt’s circle. The artist’s choice to depict him at a desk with a substantial volume is more than a genre cue; it is a succinct biography. The open book signals learning and scriptural authority, but the posture of the man—head inclined, mouth softly set—communicates pastoral temperament as much as scholarship. We meet a minister who studies not to score points but to guide souls.

Intimacy Through Scale and Framing

Rembrandt crops the figure tightly within a shallow, arched interior, a strategy that increases psychological proximity. The shoulders turn, the head pivots, and the face arrives just inside the print’s luminous center. No grand architectural setting, no heraldic display—only enough space to register the sitter’s presence. The page’s margins thus become a threshold; crossing them, the viewer enters the quiet room of Sylvius’s thought.

The Etching Medium as a Voice

Although often described as a “print,” this is above all a drawing in metal. The etched line carries a living pulse: some strokes are hair-fine and exploratory; others thicken into shadow nets; still others dissolve to let paper light speak. Rembrandt uses biting—the time the copper spends in acid—to vary depth so that a single hatch can whisper or insist. The result is a range of tones that rival brush and ink while retaining the crispness of engraved light.

A Chiaroscuro That Remembers Faces

The face is built with a mosaic of short, sensitive strokes. Light collects first on the brow ridge and the high planes of the cheeks, then travels down the bridge of the nose before settling in the albumen glow of the beard. Shadow is never a mask; it is a soft veil through which expression remains legible. Because the eyes are carved out of tone rather than traced, they keep moisture and alertness—a glimmer that suggests recent thought.

The Ruffled Collar as Theater of Texture

The small ruff is a study in economy. Rembrandt doesn’t draw each pleat; he constructs the idea of pleating with alternating triangles of white paper and crisp dark wedges. Those accents hold the head aloft like a modest stage, presenting the face without ostentation. In a print that treasures moral modesty, the collar’s restraint becomes a virtue in itself.

Clothing That Refuses Vanity

The robe and cap are handled broadly, almost abstractly. A few long, slanting hatches convey the weight and nap of cloth; the cap sits low and practical, suggesting a man who values use over display. The absence of decorative flourish is deliberate: it gives the engraving’s richest descriptive resources to the sitter’s head and hands, where identity resides.

Hands That Pray and Think

Few artists equal Rembrandt’s eloquence with hands. Here, Sylvius’s fingers interlace upon the book in a pose that balances contemplation and quiet supplication. Knuckles are indicated with quick, decisive marks; tendons and veins emerge just enough to signal age and active life. The hands are not idle props—they are the hinges between study and devotion, between the Word on the page and the person who will speak it.

The Book as Anchor and Metaphor

The open book gives the composition its physical ballast and its moral center. Rembrandt renders the fore-edge with parallel hatching and tiny darts that stand for page gatherings, then allows the sheets to flare slightly as if recently turned. It is a lived-in book, not a ceremonial tome. The diagonal of its lower edge guides the eye back toward the face, creating a loop between text and reader—a loop that names the preacher’s vocation.

A Room Made of Air and Line

Look behind the sitter and you’ll see no elaborate furnishings, only a softly arched wall, a corner, and bands of tone that shift like quiet air. This unobtrusive architecture does real work. The dark behind the head sculpts the silhouette; the lighter zone to the right opens space into which the figure can breathe. The room becomes a resonating chamber for the voice we imagine.

The Psychology of the Turned Head

Sylvius does not confront us full-on. The head pivots, inviting our gaze to meet his without aggression. This slight turn is psychologically exact: it is the posture of one who pauses in reading to address a listener, or of a pastor who has been asked a question and answers with patient clarity. Rembrandt’s portraiture is at its best when a gesture hints at narrative; here, the suggestion is that thought has just become speech.

Age, Light, and Dignity

Lines at the outer eye, a thinning crown under the cap, and the soft slack at the jaw root all mark years lived. Yet nothing is exaggerated for effect. The dignity is in the acceptance of time, in the sense that experience and humility have deepened rather than hardened the person. Rembrandt’s light treats age the way sunrise treats worn masonry: it discovers beauty in weathering.

Economy and Invention in the Background Hatching

The background’s dense netting is not filler; it is orchestration. Angled strokes bend around the curve of the wall, suggesting architecture with almost no contour. Occasional open passages—left intentionally unbitten or lightly hatched—serve as reserves of white that keep the image breathing. The eye reads these abstract fields as light bathing stone, though nothing literal is drawn.

The 1634 Moment: Youth with Authority

Dated 1634, the portrait belongs to Rembrandt’s early Amsterdam period, when the twenty-something artist was already commanding commissions and perfecting a print language that joined drawing’s quickness to painting’s depth. The assurance visible here—the willingness to leave, to abbreviate, to trust the viewer’s intelligence—announces a master who knows how little he needs to say to say something large.

Presence Without Flattery

Rembrandt’s respect for sitters never descends into softening fiction. Sylvius’s nose has its full character; the mouth keeps the slight asymmetry that makes it human; the beard is not perfume-advertisement fluff but wiry and light-catching. This honesty offers a fuller gift than flattery: a permanent likeness that loved ones would recognize and that listeners would trust.

The Print as a Social Object

Unlike a single painted panel, an etching can travel widely. This portrait could be gifted, collected, pasted into albums, or displayed in study rooms. Its portability multiplies the sitter’s presence in the world, aligning with his role as a teacher whose words circulated. Rembrandt, always alert to how images live socially, uses the medium to extend Sylvius’s reach beyond a single wall.

Echoes of Earlier Northern Portraiture

There are debts here to the Netherlandish tradition: the sober half-length scholar with book, the modest domestic interior, the textured attention to aged skin. Yet Rembrandt modernizes those conventions with a sensitivity to inner life that earlier models rarely achieve. The gaze meets ours not as a symbol of learning but as an individual mind in motion.

Micro-Narratives in the Surface

Every region of the plate tells a small story. On the book’s corner, a flick of white opens the glint of paper; on the wrist, a narrow line marks a simple cuff; along the cheek, the hatch spacing widens to let flesh read as luminous. These micro-decisions accumulate into macro-truth: we feel we have met a person in his element, at a true hour of the day.

The Hum of Silence

One of the strangest pleasures of the print is its sound: none. The closed room, the soft garment, the pages at rest—everything encourages a quiet through which the viewer hears only the imagined voice. Rembrandt engineers this silence by avoiding visual noise: no cluttered shelves, no patterned tapestry, no shiny metal. The image hums at the frequency of thought.

A Theology of Attention

Without overt piety, the portrait proposes a theology: attention itself is devotion. Light attends to the face; the face attends to the book; the hands attend to stillness; the artist attends to all. In this chain of looking and caring, knowledge becomes love. It is hard to imagine a more persuasive visual argument for the ethical power of study.

Lessons for the Eye Today

The print teaches how to look at people. Begin with their work (the book), then register their posture (inclination), then study hands (habit), then meet eyes (intention). Notice what they omit (ornament) and how they keep company with light (honesty). In a visual culture saturated with masks and performances, Rembrandt’s method remains radical: he paints people as if truth were possible.

Why This Likeness Endures

Jan Cornelis Sylvius persists not because he is famous to us, but because Rembrandt has given his intelligence and kindness formal life. The interlaced hands, the turned head, the glow on beard and brow—these make a human chord the eye can replay forever. Even when the paper yellows, the light that makes the man will still feel fresh.

Closing Reflection on Character Caught in Copper

At first glance we see a preacher at his book. Stay longer and we sense a man ready to answer, to console, to teach. Rembrandt’s lines do not lock him into a single expression; they allow the face to change as we look, the way a good conversation partner’s face changes with ours. This is the miracle of the etching: a fixed matrix that releases living time. Jan Cornelis Sylvius remains, poised between page and speech, in a light that respects and remembers him.