Image source: artvee.com

Overview of the Composition

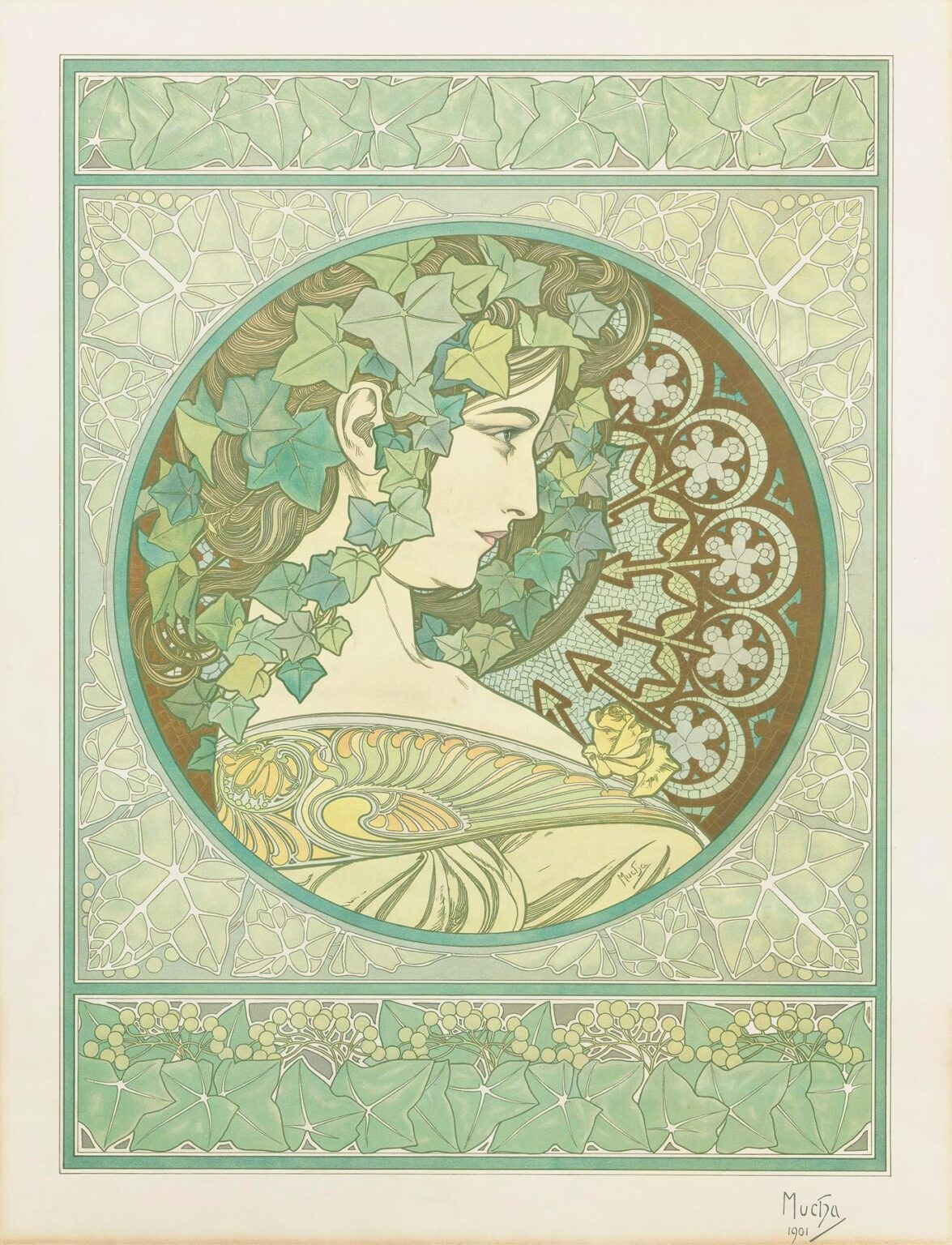

“Ivy” (1901) by Alphonse Mucha is a masterfully rendered Art Nouveau lithograph that transforms a simple botanical motif into a rich allegory of resilience, fidelity, and eternal life. The vertical format centers on a female profile, her head crowned in a tangle of glossy ivy leaves that frame her serene countenance. She faces right, her gaze directed toward an unseen horizon, while her stylized robe cascades into the dense patterning of leaves and tendrils in the background. Mucha encloses the figure within a circular medallion, itself set against a rectangular field divided by bands of ornate ivy‑leaf ornament. Executed in soft greens, muted golds, and creamy neutrals, the image evokes the hushed calm of an ancient grove. Through this composition, Mucha elevates a simple plant into a living metaphor and unifies figure, plant, and pattern into a harmonious whole.

Historical and Artistic Context

By 1901, the Art Nouveau movement had firmly taken root across Europe, challenging academic traditions and embracing organic forms drawn from nature. Mucha emerged as the poster‐artist par excellence following his breakthrough with the 1894 “Gismonda” poster for Sarah Bernhardt. In the late 1890s and early 1900s, he extended his vision beyond theatrical advertising, producing a series of decorative “Seasons” and “Flowers” panels for private patrons and gallery display. These works were widely disseminated as color lithographs, appearing in salons, department stores, and domestic interiors. “Ivy” belongs to this flowering of decorative art, reflecting contemporary fascination with symbolism, the interplay of nature and femininity, and the belief that art could ennoble everyday life.

Alphonse Mucha’s Career in 1901

The turn of the century was a peak moment for Mucha’s output. He balanced high‐profile poster commissions—ranging from commercial brands to world’s fairs—with personal decorative projects that allowed him full artistic freedom. Printing firms such as F. Champenois and U. Bong & Cie in Paris collaborated closely with him to realize complex multi‐stone lithographs. Around 1900‑1902, Mucha refined his schematic approach: he simplified backgrounds, emphasized circular frames, and harmonized figure and ornament into unified compositions. “Ivy” embodies this mature style, showcasing his command of line, color harmony, and symbolic content. It also foreshadows his later Slav Epic murals by demonstrating how an archetypal figure can represent broader themes of cultural and natural continuity.

Compositional Structure

Mucha organizes “Ivy” around a strong geometric framework. The central circular medallion encloses the female profile and overlapping foliage, creating a focal point that immediately draws the viewer’s eye. This circle is flanked above and below by wide horizontal bands filled with repeating ivy‐leaf patterns, which function as decorative anchors and counterbalance the vertical thrust of the panel. The figure’s head breaks the upper band slightly, while her drapery flows into the lower band, reinforcing the integration of figure and ornament. Behind the medallion, the rectangular field is treated as a neutral ground, allowing the decorative bands and central image to remain visually distinct yet seamlessly connected.

Use of Line and Form

Line is paramount in Mucha’s aesthetic, and in “Ivy” he exploits its expressive potential to articulate form and pattern. Strong, unbroken contours outline the figure’s profile, the shape of individual ivy leaves, and the drapery folds. Within these bold outlines, finer interior lines detail hair strands, leaf veins, and fabric textures. The repeated shapes of ivy leaves—each echoed in the border bands—create rhythm and unity. Curving forms dominate: the sinuous arc of the ivy tendrils, the gentle curve of the woman’s neck, and the rounded edges of the framing bands. These connected curves guide the viewer’s eye in a fluid dance around the composition, reinforcing the sense of living movement.

Color Palette and Lithographic Technique

Mucha’s palette in “Ivy” is characterized by harmonious greens, pale golds, and creamy neutrals. The ivy crown and background pattern employ subtle shifts from jade to olive, while the figure’s skin and drapery appear in warm ivory and champagne tones. The circular frame and decorative bands feature touches of metallic gold ink, introducing a softly reflective quality that evokes sunlight glinting through foliage. Achieving these nuanced effects required meticulous multi‐stone lithography: each hue was applied from a separate lithographic stone, and exacting registration preserved the integrity of Mucha’s intricate line work. The translucent inks overlap to produce delicate tonal variations, resulting in a luminous surface that feels both flatly decorative and richly textured.

Depiction of the Female Profile

The woman in “Ivy” exemplifies Mucha’s ideal female archetype—elegant, introspective, and timeless. Her profile evokes classical bas‐reliefs, but Mucha softens her features with modern naturalism: slightly parting her lips, modeling her cheekbones with gentle shading, and rendering her eyelids with a touch of pink. Her hair, swept back beneath the ivy diadem, flows into layered curls at the nape of her neck. This fusion of classical poise and organic vitality underscores the painting’s deeper themes: the unity of human and vegetal, the continuity of life across time, and the resilience embodied by the evergreen ivy.

Symbolism of Ivy

Ivy has long symbolized eternity, fidelity, and strong bonds—qualities rooted in its evergreen nature and its tendency to cling to and climb structures. In classical mythology, ivy is associated with Dionysus/Bacchus and with Bacchic revelry, yet it also signified enduring attachment and memory. Mucha taps into these rich associations: the figure’s unwavering gaze suggests steadfast devotion, while the circular frame echoes ivy’s looping tendrils. The ever‐present foliage implies both protection and perseverance. By crowning the figure in ivy, Mucha invests her with symbolic authority, making her a guardian of enduring natural cycles and human commitment.

Decorative Borders and Integration

Mucha’s mastery lies in transcending mere decoration: his borders in “Ivy” extend the painting’s symbolic narrative. The top band features stylized ivy leaves rendered in pale mint and gold, their interlocking shapes reminiscent of leaded glass tracery. The lower band introduces small clusters of round berries, likely referencing the ripe fruits of some ivy species. These ornamental registers are not afterthoughts; they are integral parts of the composition, echoing the central motif and reinforcing the theme of continuity. Mucha’s belief in “total decoration” is evident: every inch of the panel contributes to the overarching harmony and symbolic depth.

Light, Shadow, and Spatial Illusion

Although Art Nouveau often privileges flatness, Mucha subtly suggests spatial depth in “Ivy.” The figure’s face and shoulders receive delicate gradations of tone—darkening beneath the chin and at the hairline—to imply three‐dimensional form. The ivy leaves display simple shading on their lower surfaces, hinting at curvature. The metallic halo behind the medallion glows with a consistent intensity, suggesting a luminous backdrop. Meanwhile, the background rectangular field, left largely unshaded, recedes, giving prominence to the medallion and the figure. These selective modeling choices enrich the visual texture without undermining the painting’s decorative unity.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

“Ivy” captivates through its fusion of idealized beauty and symbolic richness. Viewers respond to the figure’s calm yet penetrating gaze, feeling both invited into her contemplative world and reminded of nature’s ever‐renewing cycle. The harmonious color scheme and rhythmic patterns impart a sense of serenity. The ivy’s symbolism of loyalty and eternity resonates on a personal level, inviting viewers to reflect on relationships, memory, and resilience. Mucha’s skillful interplay of form, color, and symbol transforms a decorative panel into a poignant meditation on continuity and growth.

Relation to Mucha’s Flower Panels

“Ivy” is part of Mucha’s broader floral series, which includes The Rose (1899), The Lily (1897), and The Chrysanthemum (1898). Each panel pairs a female archetype with a specific flower, exploring its formal qualities and cultural symbolism. Unlike The Lily’s solar motifs or The Chrysanthemum’s autumnal theme, Ivy emphasizes evergreen persistence. The series as a whole demonstrates Mucha’s belief in the unity of natural form, decorative art, and human expression. Collectively, these panels defined the visual language of Art Nouveau around the turn of the century.

Influence on Decorative Arts and Design

Mucha’s flower panels, including Ivy, had a lasting impact on decorative arts, graphic design, and ornamentation worldwide. Architects and interior designers incorporated similar organic motifs into ironwork, stained glass, and furniture. Textile and wallpaper manufacturers adapted Mucha’s sinuous lines and botanical patterns for fabrics. The seamless integration of figure and ornament in Ivy inspired later Art Déco stylists to explore new ways of unifying human and vegetal forms. In the digital age, echoes of Mucha’s design can be found in branding, packaging, and editorial layouts that seek to evoke a sense of organic luxury.

Conservation and Modern Reception

Original lithographs of Ivy are highly prized by collectors and exhibited in museums dedicated to Belle Époque graphics. The delicate early‑20th‑century papers and layered inks require precise conservation measures—UV‑filtered lighting, climate control, and acid‑free framing—to prevent deterioration. Modern high‑resolution photography and digital restoration efforts have made Mucha’s panels accessible to a global audience, ensuring that Ivy continues to be studied in design curricula and displayed in retrospectives. Its inclusion in major exhibitions on Art Nouveau underscores its status as an archetypal masterpiece.

Technical Mastery of Lithography

Creating Ivy demanded exceptional collaboration between Mucha and his printers at F. Champenois in Paris. Early color lithography required one stone for each color layer—often ten or more in a complex panel like this—and precise registration to align lines and washes. Mucha’s selection of translucent inks allowed overlapping layers to produce seamless gradations. His calligraphic lines had to remain sharp against broad color fields, a technical challenge that Champenois’s workshop overcame through skilled craftsmanship. The result is a print that retains the vitality and subtlety of Mucha’s hand‐rendered design.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Ivy (1901) epitomizes the Art Nouveau ideal of uniting nature, symbolism, and figure into a single harmonious work of decorative art. Through masterful composition, lyrical line, and nuanced color, Mucha transforms the evergreen ivy into a potent allegory of fidelity, resilience, and eternal life. The panel’s enduring appeal lies in its seamless integration of form and meaning—inviting viewers to experience both aesthetic delight and contemplative reflection. Over a century since its creation, Ivy remains a touchstone of design excellence and a testament to Mucha’s timeless vision.