Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

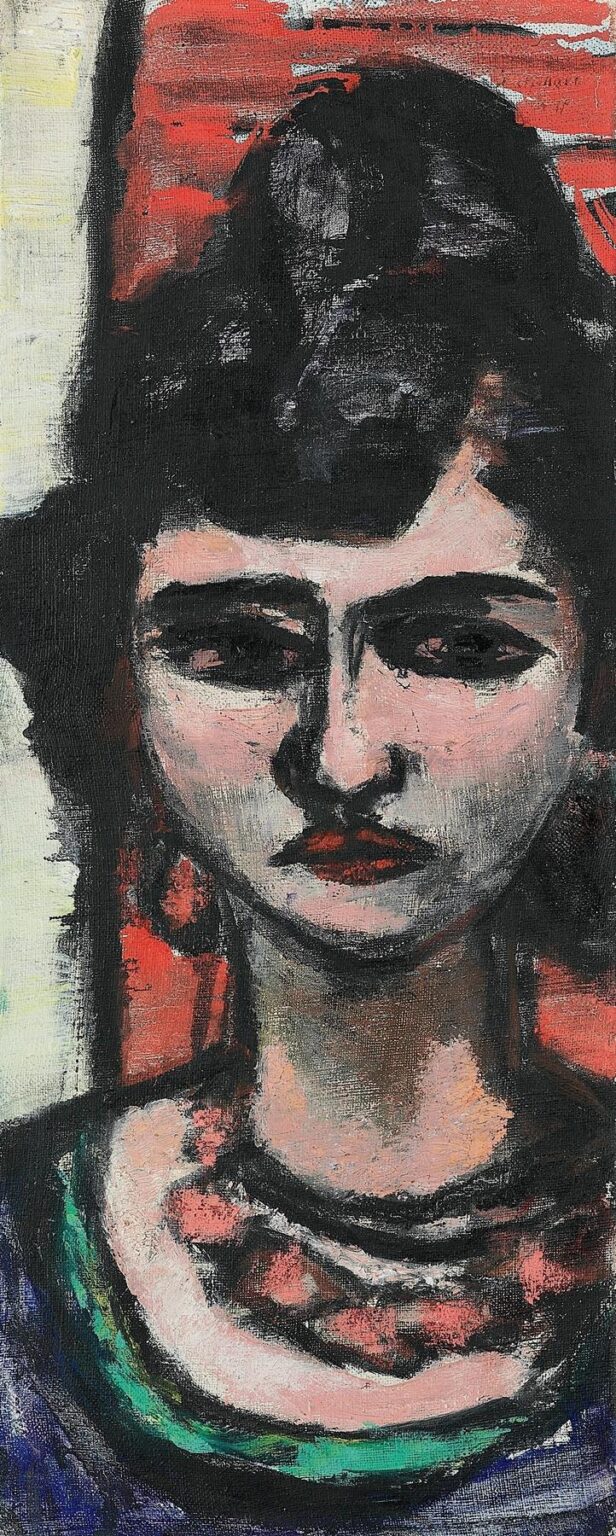

Max Beckmann’s Italian (1946) marks a pivotal juncture in the artist’s late career, synthesizing his wartime experiences, exile in the Netherlands, and subsequent relocation to the United States into a portrait that is at once intimate and archetypal. Painted in oil on canvas shortly after World War II, Italian presents a lone male figure whose stern gaze, sculptural features, and vibrant palette encapsulate Beckmann’s commitment to humanist expression amid cultural dislocation. Unlike the crowded allegorical scenes that dominated his earlier work, this portrait narrows its focus to a single individual, inviting viewers to contemplate questions of identity, resilience, and the enduring power of art. The following analysis will explore the painting’s historical context, formal strategies, chromatic choices, thematic depth, and lasting influence, revealing how Italian stands as a testament to Beckmann’s late-style mastery.

Historical and Biographical Context

In 1946, Europe was still reeling from the devastation of World War II. Cities lay in ruins, populations were displaced, and artists sought new languages to articulate collective trauma. Max Beckmann, having fled Nazi persecution in 1937, spent the war years painting in Amsterdam before receiving an invitation to teach at Washington University in St. Louis in 1947. Italian was created during this transitional period, when Beckmann grappled with exile’s emotional toll and the search for a stable artistic identity. The subject—an Italian acquaintance or perhaps a symbolic Everyman of Southern Europe—embodies the continent’s patchwork of cultures and languages, while also reflecting Beckmann’s own status as a cultural émigré. In this light, the portrait becomes both a personal encounter and a broader meditation on postwar reconstruction.

Beckmann’s Late Style: Towards a New Synthesis

Beckmann’s oeuvre is often divided into distinct phases: the ornate Jugendstil influences of his youth, the Expressionist intensity of his wartime etchings, the disciplined figuration of the Weimar years, and the allegorical dramas of exile. By 1946, his style had fully matured into what critics term his “late style”—a fusion of expressive line, bold color, and monumental form. In Italian, this late style manifests in densely layered brushwork, simplified geometry of the face, and the interaction of warm and cool hues. The figure’s head and shoulders dominate the canvas, echoing the iconic frontal portraits of Renaissance masters, yet Beckmann’s raw textures and visible strokes betray a modern sensibility. The painting thus bridges past and present, tradition and innovation, forging a new path for portraiture in the mid‑20th century.

Visual Description: Subject and Setting

Italian presents a bust-length portrait of a middle‑aged man set against a flattened, two‑color background. The sitter’s head is framed by a neutral ochre field on the left and a deep violet rectangle on the right, divided by a bold black vertical line. His dark hair and mustache—rendered in thick, almost sculptural strokes—contrast with the smooth planes of his skin, painted in warm pinks and cool whites. Heavy eyebrows cast shadows over almond‑shaped eyes that gaze directly at the viewer, conveying both intensity and introspection. The subject’s shirt collar and jacket lapels emerge from the lower edge, subtly suggested through angular, simplified forms in white and dark green. The absence of environmental detail emphasizes the sitter’s psychological presence.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Beckmann’s compositional approach in Italian relies on a harmonious interplay of horizontal and vertical elements. The vertical black line that bisects the background not only anchors the sitter’s head but also evokes the format of a diptych or altarpiece, nodding to religious art while secularizing its effect. The horizontal seam between the ochre and violet fields aligns with the sitter’s eyes, drawing attention to the gaze as the portrait’s focal point. The simplified geometry of the background juxtaposes with the organic contours of the face, creating a dynamic tension between abstraction and figuration. Beckmann compresses spatial depth, flattening the picture plane, yet the subtle modeling of the face’s planes implies sculptural volume. This duality—flatness and depth—imbues the portrait with both immediacy and monumentality.

Color Palette and Emotional Tone

Color in Italian is both descriptive and symbolic. The ochre background suggests Mediterranean sunshine and ancient stone, while the violet evokes dusk, introspection, or perhaps the bruised sky of postwar Europe. The sitter’s flesh tones—pinks, reds, and whites—are applied in layered, textured strokes that convey warmth, vitality, and the lived reality of the body. Dark greens and blacks in the hair, mustache, and clothing provide structural counterpoints, framing the face like carved marble set within a tomb. Beckmann’s cautious use of red in the lips and rosiness of the cheeks hints at passion and emotional depth. The overall chromatic scheme balances harmony with discord, reflecting both the sitter’s inner fortitude and the fractured world he inhabits.

Brushwork and Surface Texture

Beckmann’s handling of paint in Italian is vigorous and tactile. The hair and mustache are built up with dense impasto, the strokes swirling and overlapping like locks of dark foliage. The skin surfaces feature a combination of thin washes and heavier passages: the broad cheekbones reveal the canvas weave, while the forehead and nose bridge bear thicker applications that catch light. Eyebrows and eye contours are traced with confident, linear marks, lending the face a carved quality. Background fields show brush marks that are more uniform yet retain visible directionality—horizontal in the ochre, vertical in the violet—underscoring the contrast between sitter and setting. This varied brushwork creates a living surface that mirrors the complexity of human identity.

Iconographic Elements and Symbolism

While Italian appears to be a straightforward portrait, Beckmann infuses it with iconographic resonances. The vertical split may allude to the schism between public and private selves, or between tradition (ochre) and modernity (violet). The sitter’s direct gaze evokes the ancient tradition of mens sana in corpore sano: a healthy mind within a healthy body, yet here the gaze also carries the weight of wartime witness. The heavily textured hair suggests both vitality and a crown of thorns, blending pagan vigor with Christian suffering. The muted jacket, nearly abstracted, underscores the erasure of social markers—class, profession, nationality—focusing attention on the universal humanity of the face. Collectively, these symbols elevate the portrait into a meditation on identity in a fractured age.

Psychological and Emotional Resonance

Beckmann’s Italian does not simply record a likeness; it seeks to capture the sitter’s psychological core. The model’s narrowed eyes and tight lips convey determination tempered by weariness. His slightly furrowed brow suggests contemplation of recent horrors or the burdens of memory. Yet there is no overt expression of despair; rather, the portrait conveys resilience—a steadfast presence amid chaos. Beckmann believed that the artist’s task was to include the full spectrum of human emotion, not merely idealize or stylize. In Italian, the sitter stands as a representative of postwar Europe: scarred but unbroken, aware of suffering yet committed to survival.

Relation to Italian Art and Portrait Tradition

Beckmann’s choice of the title Italian invites comparison with the Renaissance masters of Italy—Titian, Michelangelo, and Raphael—who elevated portraiture to a high art. Yet his approach diverges from their pursuit of ideal beauty. Instead, Beckmann’s sitter is a real person, defined by individual idiosyncrasies rather than classical proportions. The background’s flat color fields echo Giorgione’s use of landscape yet eschew naturalistic detail. The direct frontal pose recalls Byzantine icons, where the eye engages the viewer in a spiritual dialogue. By blending these Italianate references with Expressionist urgency, Beckmann pays homage to Italy’s artistic heritage while asserting a modern, critical stance.

Beckmann’s Exile and Transatlantic Turn

After arriving in America in 1947, Beckmann grappled with cultural displacement and the challenge of teaching at a new institution. Italian was painted just prior to his departure, during a time when he revisited European subjects with fresh eyes. The portrait’s austere background may reflect Beckmann’s sense of rupture—no longer embedded in familiar landscapes, he turned inward to the human face as a primary site of inquiry. His American students, encountering his robust approach to portraiture, were struck by his fusion of European tradition and contemporary existential concerns. Italian thus occupies a transitional space: a last homage to Europe’s artistic legacy before Beckmann fully embraced his role as an international modernist.

Reception, Criticism, and Legacy

Contemporary critics recognized Italian as a significant work in Beckmann’s late period. Its stripped-down composition and emotional directness resonated with postwar sensibilities, while its technical mastery affirmed Beckmann’s status as one of the twentieth century’s preeminent portraitists. In subsequent decades, the painting has been studied for its innovative merging of Expressionism and New Objectivity, as well as for its nuanced portrayal of exile. Scholars have noted how Italian prefigures later European portraiture that emphasizes psychological presence over decorative detail. The painting’s legacy endures in its capacity to evoke universal themes of dislocation, survival, and the enduring power of the human face.

Conclusion

Max Beckmann’s Italian (1946) stands as a masterful convergence of historical witness, artistic tradition, and psychological depth. Through its bold use of color, textural brushwork, and simplified yet monumental composition, the portrait transcends mere likeness to explore themes of identity, resilience, and the scars of war. Beckmann’s choice to focus on a single figure—framed between warm ochre and cool violet fields—distills his broader concerns into an intimate dialogue between sitter and viewer. As both a document of postwar Europe and a timeless reflection on human presence, Italian reaffirms Beckmann’s vision of portraiture as an art capable of bearing witness to suffering while affirming the indomitable spirit of humanity.