Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

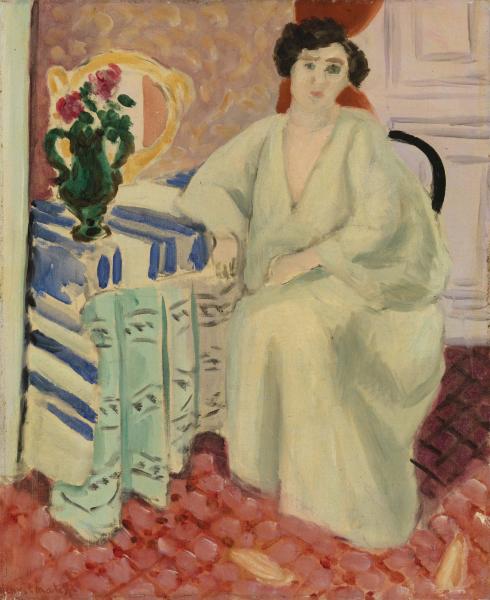

Henri Matisse’s “Interior with Seated Figure” turns a modest Nice apartment into a stage where color, pattern, and poise perform in concert. A woman in a pale robe sits beside a table draped in blue-and-white stripes. On the tabletop, a green jug of flowers and the warm oval of a golden-framed mirror balance the composition’s cool notes. Beneath everything, a coral-red, pebble-like carpet hums with a steady rhythm. A sliver of paneled door, a dark chair rail, and a folded length of patterned fabric complete the room’s grammar. With disarmingly economical strokes, Matisse builds an interior that feels welcoming and structured at once—an architecture of comfort.

The Nice Period’s Language of Calm

Painted in the early 1920s, the canvas belongs to Matisse’s Nice period, when he refined an art of balance after the incendiary experiments of Fauvism. Chromatic fire gives way to climate; drawing loosens from description and becomes an elastic contour; pattern serves as structure rather than mere decoration. Domestic spaces—armchairs, tablecloths, flowers, mirrors—become laboratories for clarity. “Interior with Seated Figure” embraces this program: it does not shout; it sustains. The picture proposes that serenity, thoughtfully arranged, is a modern value.

Composition as Architecture

At first glance the scene looks casual, but its geometry is exact. The seated figure forms a large, pale mass set slightly right of center; the table creates a strong vertical block on the left; the top edge of the tablecloth establishes a stable horizontal that anchors the room. The round mirror above introduces a counter-shape—an oval that relieves the rectilinear scaffolding—while the vase’s dark green body acts as a vertical accent within the table’s rectangle. The chair’s curved back peeks in as a black semicircle, echoing the mirror at a smaller scale. This interplay of rectangle, oval, and arc holds the interior together with understated rigor.

The Seated Figure as Quiet Center

Matisse renders the woman with the fewest means necessary: a softened contour for shoulders and sleeves, a hint of clavicle at the V of the robe, a compacted ellipse for the head, and facial features gathered in a handful of marks. The posture is composed rather than stiff—one arm settled on the table’s edge, the other gathered into the lap. Because the garment is nearly the same value as the surrounding wall, the figure doesn’t dominate; she inhabits the room. That humility is essential to the painting’s ethic. The person belongs to the environment she has arranged; the environment responds to her presence.

Color Climate: Mint, Ultramarine, and Coral

The palette is tuned like chamber music. Cool greens and blues lead: the striping on the tablecloth, the patterned fabric hanging from its edge, and soft mint notes in the robe. Warmth arrives in counterpoint through the coral-red carpet, the ochre panel behind the mirror, and the flushed blooms in the green jug. The white of the paneled door and the pale field of wall calm the ensemble, while black accents—the chair’s arc, the vase’s mouth, dark blue touches in the stripes—ground it. No single color steals the show; each is negotiated against its neighbors until the room feels breathable.

Pattern as Structure, Not Ornament

Matisse deploys three distinct patterns, each with a job. The blue-and-white stripes of the tablecloth set the tempo—regular, measured, and directional, pulling the eye down the left side toward the draped, patterned textile. The hanging fabric’s repeating motifs (small diamonds or lozenges) slow the rhythm, thickening the visual texture near the floor and linking cloth to carpet. The carpet itself—clusters of coral and rose—operates like a bass line, steadying the composition while warming the lower register. Pattern isn’t a flourish here; it is the way the painting keeps time.

The Mirror’s Double Service

The round, gold-framed mirror is both device and metaphor. As device, it plugs an otherwise blank wall with a radiant oval, echoing the sitter’s head and the curve of the chair back while spreading warm color into the upper left. As metaphor, it stands for reflection—mental and optical. You sense room and light recirculating through it, but Matisse keeps the surface painterly, preserving the integrity of the canvas. The mirror expands the perceived space without breaking the picture’s flat harmony.

The Green Vase and the Logic of Accents

The dark green jug, compact and sculptural, anchors the tabletop and prevents the left half from evaporating into light stripes. Its color recurs, more gently, in the sitter’s robe and the hanging cloth, knitting figure and furniture. The bouquet’s pinks and reds echo the carpet’s coral, sending warmth upward so the composition doesn’t bottom out. A small white highlight on the jug’s shoulder gives just enough sheen to assert volume; any more would break the mood.

The Table as Stage

The table’s edge and cloth form a small theater for Matisse’s favorite motifs: stripes, a vessel, flowers, and the edge of a mirror. Notice how the stripes bend over the corner, how the draped fabric’s verticals intersect them, and how a narrow strip of tabletop peeks out under the vase’s base. These intersections provide the picture’s tactile pleasures. The table is not just a piece of furniture; it is where color planes meet and test one another.

Light Distributed Like Air

Instead of a single directional spotlight, the painting uses light as a network of relationships. The white of the robe is cooler than the white of the door; the tablecloth’s highlights sit a degree above the robe; the mirror’s gold picks up a warm glow that impulses outward into the wall. Because whites are carefully differentiated and warms and cools are balanced, the room feels evenly lit. This distributed light is crucial to the Nice interiors: it makes the spaces inhabitable rather than theatrical.

The Living Contour

Matisse’s line carries the composition without imprisoning it. It thickens where support is felt—the table’s corner, the edge of the chair—then thins across breathy passages like the robe’s hems. On the face, a few dark strokes—brow, eye, lip—are allowed to sit prominently; elsewhere line softens into color. The contour functions as a conductor: it cues entries, sets tempo, and keeps disparate sections playing together.

Brushwork and the Evidence of Decision

Everywhere the surface shows confident edits rather than labored rendering. The carpet is made of quick, rounded dabs that congeal at distance into a humming field. The wall behind the mirror is scumbled, allowing undercolor to flicker through. The robe is laid in broad, semi-opaque planes that keep folds generalized. The vase is built with slower, loaded strokes to emphasize its weight. These varied touches tell you what matters: structure, rhythm, and temperature—not minute description.

Space and Depth Without Pedantry

Depth arises from overlap and value steps. The sitter overlaps the table; the table, the wall; the carpet slides under both and rises slightly at the front edge—Matisse’s favored modern tilt. The paneled door is flattened into elegant rectangles that imply recess without drawing a receding box. The effect is a space you can imagine entering, though the painting never lets you forget the surface that generates the illusion.

The Viewer’s Circuit

The painting invites a looped viewing path. One typically begins at the sitter’s face, drops to the robe and hand resting on the table, glides along the blue stripes to the vase and mirror, travels down the hanging cloth to the carpet, and then ascends the right-hand edge past chair arc and door back to the face. Each circuit yields a new pleasure: a pale seam at the robe’s neckline, a reflected echo of pink in the mirror’s interior, a darker blue accent in a stripe, a warm pebble of carpet that catches a touch more light.

The Ethics of Comfort

Matisse’s Nice interiors make a quiet moral argument: comfort is worthy of art. “Interior with Seated Figure” dignifies unhurried time. The chair supports rather than exhibits; the table offers flowers rather than trophies; the palette steadies the nerves. In an age that often equated modernity with agitation, Matisse offers another version: composure built from attention to color and proportion, a hospitality of space.

Clothing and Modern Ease

The sitter’s robe is loose, domestic, and contemporary, signaling ease rather than display. Its minty coolness tempers the heat of nearby warms and aligns her with the room’s clarity. By refusing elaborate modeling, Matisse grants the garment a functional elegance; it’s all about fit—of person to place, of color to climate. The figure becomes an emblem of modern ease rather than an object of spectacle.

Mirror, Memory, and Self-Containment

The mirror’s presence invites thoughts about interiority. We can’t see the room’s window, but we feel daylight redistributed by reflected surfaces. The mirror also keeps the composition self-contained: even as it hints at an unseen space, it returns those hints to the painting’s center. The effect is one of completeness. The world may extend beyond the frame, but everything required for a satisfying harmony is already inside.

Patterned Carpet as Ground Rhythm

The coral carpet does heavy lifting. Its pebble-like marks are not fussy flowers; they’re beats. The red-pink temperature secures the composition’s base while sending warmth up into the figure’s cheeks and the bouquet. A few brighter “stones” near the sitter’s feet keep the rhythm from going mechanical. Matisse knows that ground without music is dead; here the carpet’s murmur keeps the whole room alive.

Kinships With Sister Works

The painting speaks fluently with other interiors of 1920–23: the blue-striped tables, anemones in jugs, mirrors, armchairs, and figures in robes recur like familiar words in new sentences. Compared with the later odalisque rooms, this interior is sparer, its patterning restrained. Compared with Fauvist portraits, chroma is tempered and value modulation more important. Yet the grammar is consistent across Matisse’s career: large, legible shapes; a few color chords; and a contour that breathes.

Sensation Over Description

Matisse is not cataloging objects; he is staging sensations. The cool of a striped cloth under the hand, the faint gleam of a glazed jug, the resilient give of a thick carpet, the calm of white walls toned just warm enough to hold flowers and skin—these experiences are transposed into relations of color and edge. The painting persuades the senses not by detail but by rightness of relationship.

Why the Image Endures

“Interior with Seated Figure” lingers because it offers a room the eye can inhabit without fatigue. Its order is legible at a glance and generous in depth. The composition gives you a dependable circuit; the colors meet in the middle rather than at extremes; the brushwork is frank enough to feel intimate but controlled enough to sustain poise. The result is a portable calm—an interior you can return to and re-enter, confident that the furniture of light and color will still be in its right place.

Conclusion

Matisse’s interior is a manifesto of sufficiency. A seated woman, a striped table, a green jug with flowers, a mirror, a carpet—nothing more is needed to achieve equilibrium when each element is tuned to the rest. Pattern keeps time; contour conducts; color sets the temperature; light distributes kindness. The figure is not an ornament to the room, nor the room a neutral shell for the figure. They complete each other. In that mutual fit lies the painting’s lasting grace.