Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

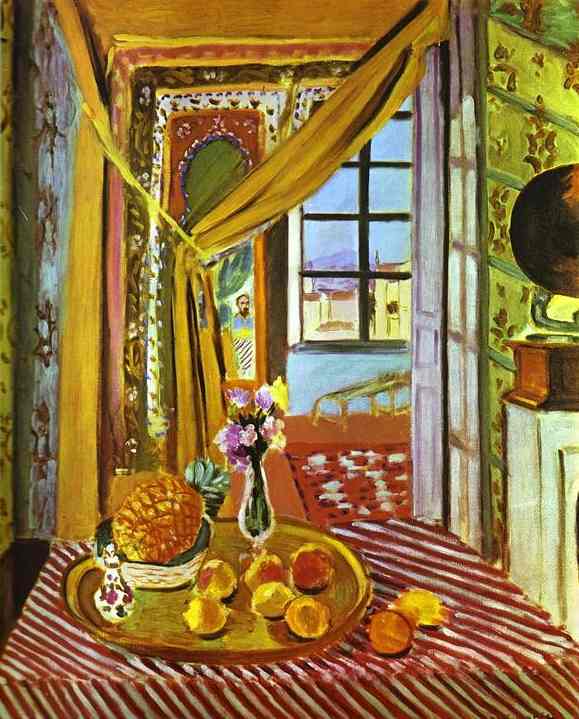

Henri Matisse’s “Interior with Phonograph” (1924) stages a sun-filled room as a living instrument, tuned by color, pattern, and light. In the foreground a striped cloth spills diagonally across a table, supporting a brass tray of fruit and a small vase of flowers. Curtains the color of pressed lemons billow from the left and gather above a doorway. Beyond them we glimpse another chamber, a patterned screen, a bed, tiled floors, and, through a black-gridded window, a bright slice of town and distant hills. At the far right, a phonograph with its dark horn perches on a cabinet like a sculpted note. The picture is both intimate and expansive: a domestic still life that opens onto architecture, landscape, and sound. What begins as a tabletop arrangement becomes a symphony of relationships, the room itself resonating like a body of music.

Historical Context and the Nice Period Interior

Painted in Nice in 1924, the work belongs to Matisse’s celebrated “Nice period,” during which he traded Fauvism’s violent contrasts for a luminous classicism. The Mediterranean climate offered ambient light that flattened glare and allowed color to breathe. In rented apartments he assembled staged interiors—curtains, screens, carpets, furniture, patterned wallpapers, musical instruments—and explored how a “democracy of surfaces” could replace deep space and theatrical chiaroscuro. The phonograph, a modern device for domestic listening, fit naturally into this program. It bridges the cultivated leisure of earlier still lifes with the new technologies of the 1920s, aligning sound with pattern, rhythm with ornament. This painting joins Matisse’s family of window pictures, where rooms and views become interlaced registers of light.

Composition as a Processional of Spaces

The composition advances like a procession from near to far. The striped cloth sweeps from the lower right toward the center, pulling the eye to the golden tray. From there, the gaze climbs to the flowers, then passes under the draped curtains into the middle room with its tiled floor, then to the black-gridded window, and finally to the lavender hills. Matisse casts the interior as a corridor of intensities rather than a tunnel of perspective. Each threshold is marked by a change of tempo: wide diagonal stripes, then concentrated fruit and flowers, then the soft folds of curtains, then the checkered floor, then the quiet grid of the window. The phonograph’s horn counters this procession by anchoring the right edge with a round, dark mass, ensuring the composition does not drift seaward through the window but returns to the present warmth of the room.

Pattern as Architecture

In place of receding lines, pattern builds the interior’s architecture. The tablecloth’s red-and-white diagonals establish the near plane and energize the foreground like a musical ostinato. The doorway is framed by curtains whose folds act as slow verticals, toning down the stripes’ speed. Beyond, an ornate screen and a patch of red-and-white tile reassert rhythmic order in the middle ground; the window grid is the final, clarifying measure—the simplest pattern, functioning as both frame and pause. Even the wallpaper at right carries vegetal motifs that echo the fruit and flowers, binding wall to table. Pattern determines distance here: big stripes near, small tiles middle, quiet grid far. The room feels deep yet remains physically shallow because every surface insists on its own pulse.

Color Climate: Gold, Carmine, Verdigris, and Sky

The palette is a saturated chord. Lemon-gold curtains and ochre woodwork bathe the left half in warmth. Carmine stripes and the burnished tray intensify that heat, while the fruit—orange, lemon, and the rough amber of a pineapple—repeat the golden register in several textures. Balancing this are cools: the sky’s blue-violet through the window, a lavender wall in the distance, and touches of verdigris in shadows and foliage. The phonograph horn is a deep chromatic brown, not dead black, so it participates in the room’s warmth while retaining gravity. Nowhere does color sit inert; it circulates like air. Warm notes advance, cool ones recede, and the whole canvas breathes with measured temperature.

Light Without Theatrics

Nice light is even and benevolent, and Matisse allows it to settle gently across objects and fabrics. Highlights are milky, slow—on the tray’s rim, on the fruit’s rinds, on the vase’s neck. Shadows are translucent—plum along the folds of the cloth, olive at the base of the tray, violet in the corners of the room. Because no area is evacuated by black, nothing becomes a hole; every form keeps chromatic life. This equalized illumination preserves serenity even as color sings. We are not witnessing a single dramatic instant but a sustained noon of attention.

The Foreground Still Life as Tuning Fork

The tray of fruit and flowers is the painting’s tuning fork. The pineapple’s rugged geometry breaks the smoothness of cloth and metal; its amber pips are tiny echoes of the striped rhythm beneath. Oranges and lemons, scattered with casual inevitability, place round warm notes against the tray’s oval. The glass vase with its bouquet rises like a treble clef, centering the foreground and pointing toward the curtain’s knot, which then directs us into the next room. Every quantity is judged: enough fruit to build a chord but not a narrative; enough shine to animate the tray but not blind the eye; enough floral color to bridge cloth to curtain and interior to exterior.

Curtains as Stagecraft and Breath

Matisse uses curtains like stagecraft: they declare space and control tempo. Here the left curtain opens like a golden wing, while a second fold drapes the threshold and bounces warm light into the middle room. Their soft arcs oppose the strict diagonals of the cloth and the right angles of the window, keeping the geometry humane. They also behave like lungs for the painting: the eye inhales as it moves into the folds, exhales into the tiled space beyond. Curtains enable Matisse’s favorite maneuver—turning a deep interior into layered planes that remain right up on the surface.

The Black-Gridded Window and the World Beyond

The window’s grid is a moment of deliberate quiet after the interior’s decorative crescendos. In the distance, pale buildings and a purple ridge draw a thin, cool band through the warm house. This view is not a landscape in competition with the room; it is a cool reply to the interior’s heat, the final rest in the composition’s phrase. The grid reminds us that we are still in a designed space; the outdoors is admitted on Matisse’s terms—flattened, patterned, composed.

The Phonograph as Modern Emblem

On the right, the phonograph anchors the painting’s modernity. Its dark horn and cabinet form a second still life—pure silhouette, minimal description. Against the patterned wallpaper it reads as a small monument to sound. Conceptually it connects the room’s visual rhythms to musical ones: stripes like measures, tiles like beats, fruit like notes, curtains like dynamics. The phonograph signals that this is a house where listening and looking are allied practices, where technology and ornament happily coexist. Its presence also prevents nostalgia: the interior may be drenched in exotic textiles, but the world includes recorded music and contemporary leisure.

Spatial Layers Organized by Tempo

Matisse’s depth is governed by tempo rather than vanishing points. The near field is fast—the flicker of stripes. The mid field is moderato—the tray’s oval, the bouquet’s vertical, the curtain’s fold. The far field is adagio—the tiled floor’s small checks, the window grid’s quiet crossings, the lavender hills’ soft gradient. By staging space as changes of rhythm, the artist keeps the entire surface alive while offering the viewer a clear path through the picture. We feel distance as a slowing of pattern and a cooling of color, not as a mathematical recession.

Drawing and the Economy of Means

Look at the pressure of the brush. The tray’s ellipse is a decisive loop, weightier on the near side, thinner where it turns in space. Fruit edges are quick, compressed strokes; the vase is a few firm facets with a single highlight to state glass. The curtain’s folds are long, breathing pulls; the window’s grid is drawn with a human wobble rather than a ruler’s chill. Everywhere description stops the moment structure stands. This economy leaves room for color and light to complete the sensation, maintaining the freshness of the surface.

Touch and Material Presence

The painting invites the hand as much as the eye. The cloth is laid with brisk, slightly dry strokes that let the ground sparkle through, mimicking the weave. The tray’s brass is a denser paint that catches light along edges and dimples. The pineapple is scumbled with small ridged strokes to state its prickle; the oranges are smoother; the lemons show a thin scraped highlight. The curtain’s paint is buttery, pooling where the fold turns. Even the wallpaper’s motifs are dabbed with a springing touch that keeps them from curdling into pattern for pattern’s sake. Material presence becomes an argument: painting itself is the room’s most convincing texture.

Dialogues with Neighboring Works

“Interior with Phonograph” converses with Matisse’s Nice interiors across these same years. The brass tray and fruit recall “Still Life with Pineapple” and “Still Life, ‘Histoires Juives’,” while the window-through-room structure echoes “Vase of Flowers” and “Young Woman Playing Violin.” The drapery’s golden chord and the ornamental screen nod to his odalisque series, but here the human figure gives way to the phonograph—a substitution that tilts the interior from sensual theater toward a meditation on rhythm and listening. The painting also quietly cites “The Red Studio” (1911): a room that is a mind, objects organized as a single visual tempo. In Nice Matisse translates that radical flatness into livable light.

Meaning Through Design

What, finally, does the painting propose? That a room can be composed like music. Stripes, tiles, grids, and folds become meter and phrase; fruit and flowers are color notes; brass and glass are timbres; the phonograph is both subject and metaphor. The design dignifies everyday objects by placing them in measured relation. Nothing is anecdotal: there is no story to the fruit, no romance to the curtains, no sentiment about the distant town. Instead there is an ethic of attention. The painting models a way to live with things—arranging them so that looking feels like listening and time expands within a calm, lucid order.

How to Look, Slowly

Enter at the lower right where the stripes flare. Let their diagonal carry you to the tray’s near rim; feel the oval’s weight shift as the line thins and thickens. Count the fruit like beats: orange, lemon, lemon, orange; pause at the pineapple’s clustered pips. Rise with the vase into the yellow fold above; follow the curtain’s arc to the doorway and step into the checkered floor. Slow down at the window’s grid; breathe the lavender air beyond. Return along the wall to the phonograph; notice how its dark, round horn balances the tray’s bright oval. Drift back to the table’s stripes and begin again. Each circuit clarifies relations—warm to cool, curve to line, near to far—until the whole room begins to hum.

Conclusion

“Interior with Phonograph” is one of the clearest statements of Matisse’s Nice-period creed. Pattern is architecture, light is ambient, color carries mood, and drawing is pared to what the form needs to stand. The foreground still life tunes the picture; the curtains regulate time; the window releases a cool breath; the phonograph affirms that the rhythms of modern life belong in the same key as flowers and fruit. The canvas remains persuasive because it demonstrates a usable wisdom: attention thrives in designed relations. In Matisse’s hands, an ordinary room becomes an instrument, and looking becomes an act of listening.