Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Room Tuned Like an Instrument

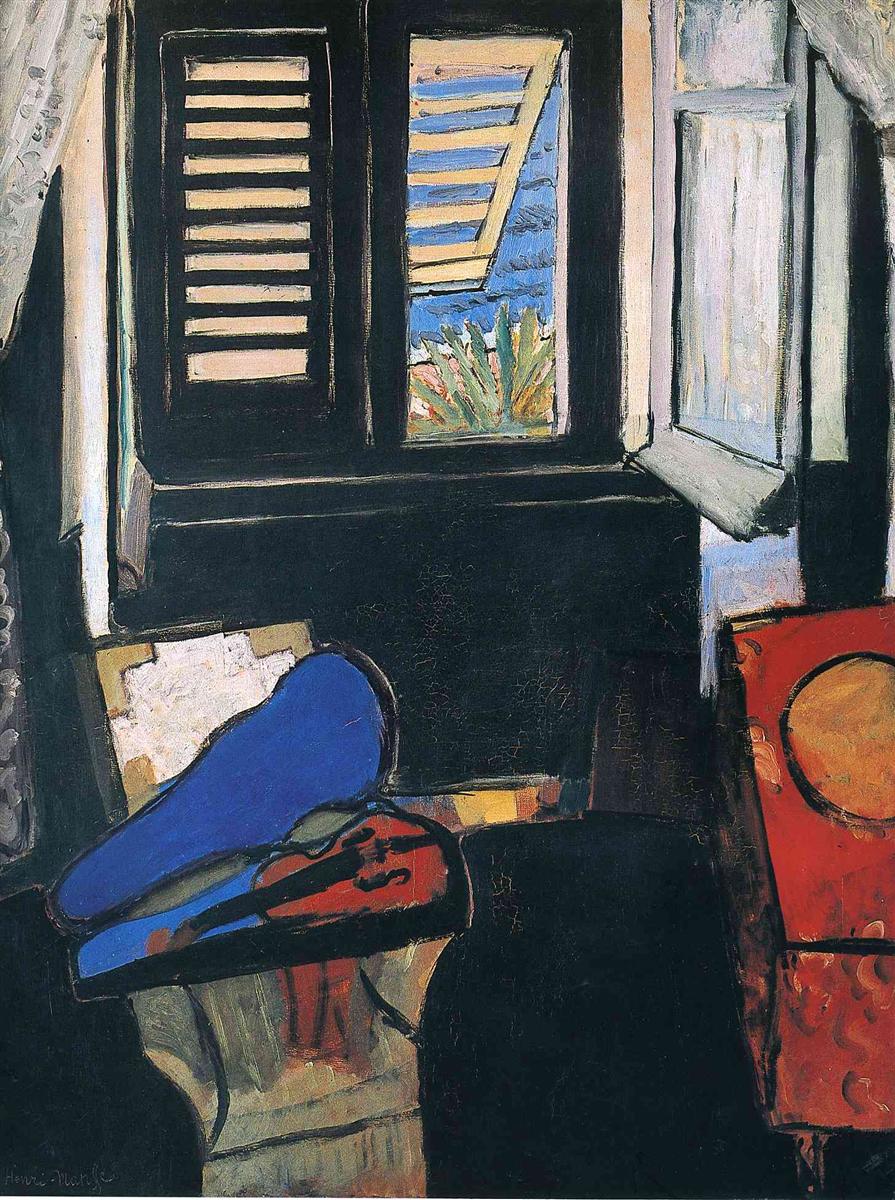

“Interior with a Violin” captures a striking conjunction of elements: a darkened room, a shuttered window split by one open casement, a sliver of Mediterranean blue beyond, and—on a small stand in the foreground—a violin set against its brilliant blue case. The interior is weighted by deep blacks and umbers, yet the picture never feels heavy; the openings of window and color act like resonant cavities that let the image breathe. At right, a red table with a circular motif glows like an ember. The composition reads instantly as a poised modern still life, then expands into an architecture of light, music, and memory.

1918 and the Nice Period Turn

Painted in 1918, this canvas stands at the threshold of Matisse’s Nice period. Coming out of the carved, high-contrast idiom of the mid-1910s, he turns toward rooms suffused with “climate light,” where calm, tuned chords replace earlier shock color. The artist settled in southern hotels and apartments and repeatedly painted their windows, shutters, balconies, instruments, and patterned tables. “Interior with a Violin” is a keynote for that shift: black is treated as a positive color; light is distributed, not dramatic; and the room becomes a stage where simple objects—violin, case, table, shutter—play leading roles.

Composition as a Network of Hinges

The design is built from hinges that pivot the eye. The far wall is dominated by a black window with two shuttered panes; between and beside them, an open casement cuts a diagonally thrusting wedge that leads outward to blue sea and spiky green foliage. That luminous wedge is balanced below by the diagonal of the violin case, whose saturated blue repeats the sky’s chord on a nearer plane. The warm red of the violin itself, nested inside the case, echoes the red table at right; those two reds strike a cross-room dialogue that keeps the dark field from feeling inert. At the left margin, a scalloped white curtain presses inward like a soft counterweight. Each element is simplified to its compositional work: shutters = stripes and blockage; casement = vector and air; instrument = color accent and lyrical contour; table = warm platform and circular pause.

The Window as Portal and Meter

Windows in Matisse are never mere openings; they measure the room’s rhythm. Here, the closed shutters are painted as dense black rectangles barred by pale slats, a visual drumbeat that slows the eye. The open casement, by contrast, accelerates: its angled sides and foreshortened louvers suggest motion and reveal the bay’s blue. One perceives not just inside and outside but two distinct meters—slow, steady bars at left; quick, syncopated accents at center-right. That difference in tempo is essential to the painting’s musical identity.

Black as a Living Color

Few painters grant black the vitality Matisse does. In this picture, black lays the ground for everything: the wall around the window, the sill, the recesses of furniture, the shadowed void of the room. Yet the black shifts in temperature and density: cool near the open window, warmer along the lower wall, oily within the violin’s outline. It acts like a bass register against which blue, red, and cream can sound. Because black is pigment, not emptiness, the interior remains luminous despite its darkness—like the interior of a violin, dark but resonant.

A Chord of Blue and Red, Tuned by Neutrals

The palette is deliberately spare. The violin case is an electric cobalt-ultramarine that rhymes with the sky beyond the shutters; the instrument is a hot red-orange tempered by brown notes at its bouts; the table at right is a red field with a circle of ochre that reads as plate or pattern. Between these primaries, Matisse threads creams, greiges, and warm whites—the slats of the shutters, the curtain, the small papers beneath the case, and the inner faces of the window. These neutrals don’t fill space; they adjust temperature, allowing the primaries to remain saturated without shouting. The color logic is simple and memorable: blue/sea and case; red/violin and table; black/room and frame; cream/air and touch.

Light as Climate Rather Than Event

There is no spotlight in this interior. Illumination is a soft, distributed climate that slides across surfaces and makes their differences legible. The open casement admits sea light, which cools the nearby wall and whitens the window’s inner faces. The shuttered panes absorb it and return only a faint, pale cadence along the slats. The instruments on the stand catch that light obliquely; their colors remain saturated but feel quietly lit. In this climate, the room’s darkness reads as chosen key, not deficiency.

Space Kept Close to the Picture Plane

Matisse builds space by overlap and value, not by deep perspective. The stand with violin and case sits emphatically near, cut against the black field like a collage shape. The red table slides into the lower right corner, its circle cropped, stressing the painting’s surface. The window recess and sill provide just enough depth to feel like architecture; the exterior view is a compact, bright panel set just behind the shutters. Because depth is kept near the plane, the composition can function simultaneously as a designed surface and a coherent room.

Drawing Inside Color

The picture’s contours—of case, violin, shutters, and casement—are drawn with brush and pigment, not with a separate outline. The black seam around the blue case is both edge and tone; the violin’s f-holes and bouts are described with elastic, warm darks; the shutter slats are laid with creamy strokes pulled over black so they read as both bars and passages of light. This integration keeps the image from feeling diagrammatic; drawing and color carry one another.

The Violin as an Image of Sound

Still-life instruments are traditional symbols of music and time, but Matisse’s violin is more than emblem. Placed on its blue case, it looks like flame on water, a red contour buoyed by blue. The viewer senses vibration rather than hears it—the arcs of the bouts, the quick darks of the f-holes, the subtle twist where the instrument’s neck would run beyond the case’s edge. Set in a room defined by bars (shutters) and circles (table plate), the violin’s asymmetrical curves supply the image’s melody.

The Table’s Circle and the Motif of Order

At right, a cropped red table holds a large ochre circle—a plate, a round of fruit, or a cloth medallion. Whatever its literal identity, it functions as a counter-motif to the shutter bars and violin curves. Circles in Matisse often stabilize interiors; they are slow forms that quiet agitation. Here, the circle’s warm color mirrors the violin’s and helps coordinate the composition’s two warm anchors across a sea of black.

Curtains, Papers, and the Ethics of Touch

The scalloped white curtain at left and the small stack of papers beneath the case are inventions as much as reports. Both are painted with airy, semi-opaque strokes that register as touch—human presence—but without anecdote. They affirm the room’s status as a place of work and attention. The papers also mediate between instrument and stand, preventing the blue case from fusing with the dark support and adding a necessary breath of light at the base of the color chord.

A Theology of Inside and Outside

One of the Nice period’s central dramas is the relationship between interior and exterior, privacy and public light. In this painting, the shutters declare the right to close off the world; the open casement asserts the right to admit it. The sea beyond is not vast but framed, a rectangle of blue and a tuft of green. Matisse proposes that true openness happens from a situated interior; you don’t abandon the room to reach clarity, you tune the room so light can enter and be held.

Surface and the Visible Time of Making

The paint surface keeps time. The black fields are layered and slightly grained; you can feel the brush changing direction to seat the window’s bands. The blue case is laid with fuller body, allowing the pigment to bloom; the red table shows streaks and scrapes where thin paint reveals undercolor. Look closely and you’ll see small corrections—a restated edge on the case, a sharpened slat on the shutter, a softened seam on the casement—honest traces of decisions left in place. Finish is achieved by relational rightness, not by cosmetic sealing.

Guided Slow Looking Through the Room

Begin at the open casement, where stepped slats angle outward to admit the bay’s compact blue. Let your eye fall to the sill and slide left across the shutter bars—pale over black, a gentle percussive rhythm. Drop to the stand: the violin’s red arcs nest in the blue case, a warm flame floating on cool. Drift right into the room’s dark pool until the red table appears, its ochre circle quiet and steady. Rise again to the window’s inner faces, white and cool, and back to the casement’s wedge of sea. After a few circuits, the room’s pulse becomes bodily: bar, wedge, curve, circle; inside, outside, inside.

Comparisons within the Nice Suite

“Interior with a Violin” speaks to Matisse’s contemporary works of windows and balconies, yet it is moodier than many. In the bright balcony pictures, stripes of sun and shadow animate floors like music staves; here, darkness contains the chord. In the open-window paintings, the view can dominate the surface; here, the view is a shard, and the instrument claims the foreground. The painting shares DNA with his still lifes on red or patterned tables, but the role of black sets it apart, giving the room the resonance of a sound box.

The Poetics of Restraint

What makes the canvas modern is not novelty of subject but exact restraint. The number of shapes is few; the color set is limited; the drawing is succinct; yet the experience is rich. This economy amplifies meanings. Black becomes space and sound; blue becomes distance and object; red becomes warmth, music, and domestic ceremony; cream becomes edges of light. Matisse trusts that a handful of exact relations can carry more truth than a tangle of detail.

Emotion Without Anecdote

There is no figure; there is no depicted performance; still, the painting is full of feeling. The weight of the dark field suggests evening or the quiet before work resumes. The violin lying in its open case suggests pause, not abandonment. The cut circle at right evokes a table set for solitary concentration rather than social feast. Emotion forms as a weather—calm expectancy—produced entirely by light, shape, and color.

Lessons the Painting Offers

For painters and designers, the canvas is a compact manual. Use black as a living color to stabilize pale chords. Keep depth near the plane so surface and space are read together. Build a room around a few durable motifs—bars, wedge, curve, circle—and let color do the expressive labor. Model by temperature rather than heavy shadow to preserve air. Above all, stage the exchange between inside and outside; clarity often arrives through a controlled opening rather than through spectacle.

Why It Still Feels Contemporary

A century later, “Interior with a Violin” reads as current because it understands attention. It offers a limited set of elements arranged for sustained looking, much like a well-composed screen or a minimalist room. Its colors are memorable and brand-clean—a cobalt, a lacquered red, a field of black, a few creams—yet never slick, because the hand remains visible. It honors craft and calm in a way that resists noise, making it endlessly livable.

Conclusion: A Room Tuned to Hold Light and Sound

“Interior with a Violin” is more than an inventory of objects. It is a proposal about how to live with light and music: keep a dark, resonant interior; open a measured portal to the world; tune a few colors until they sing; leave the marks of making visible so time can move inside the room. The violin rests, the sea glints, the shutters beat a soft measure, and a circle on a red table holds the composition’s quiet center. Matisse gives us not just a scene but a way of breathing.