Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

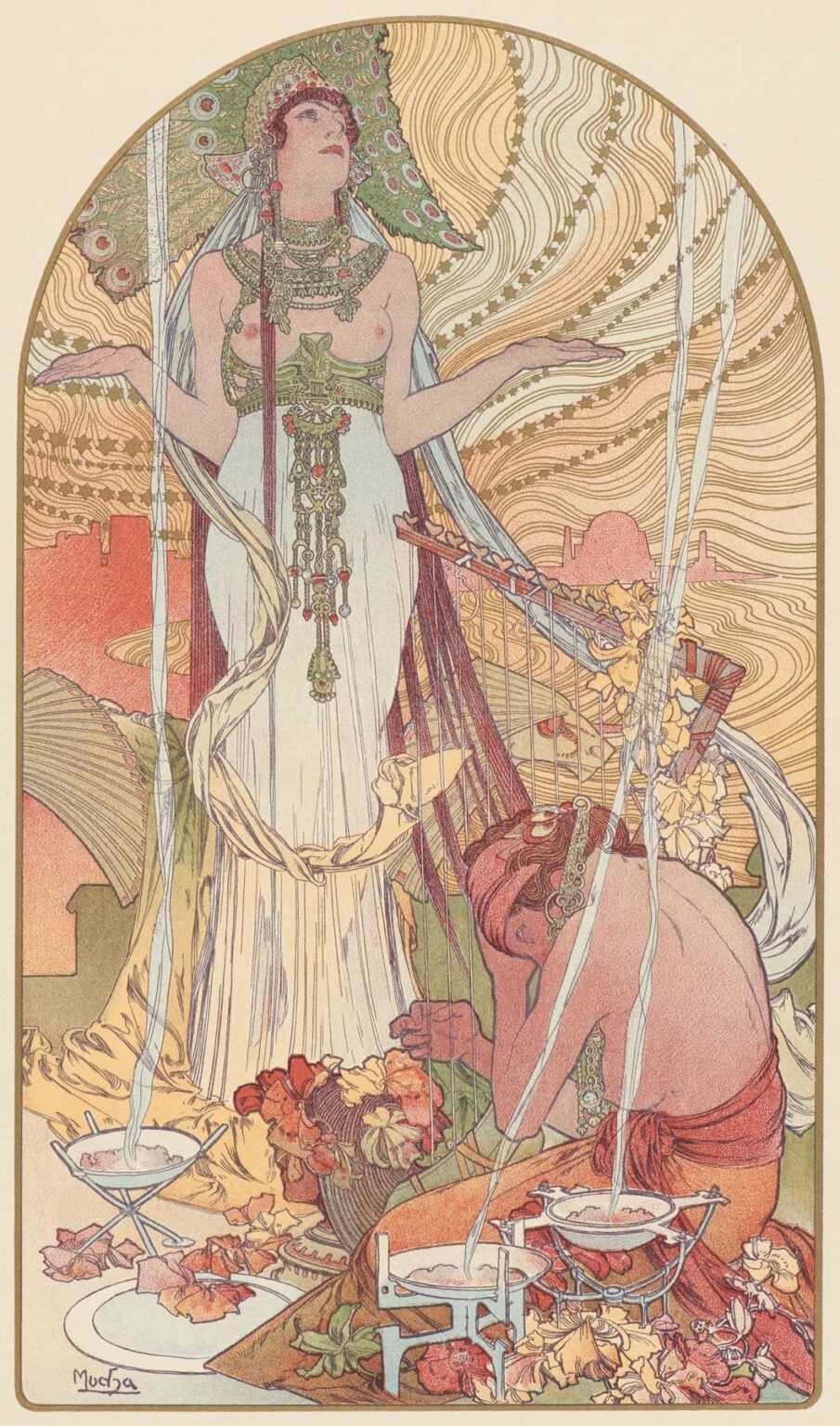

Alphonse Mucha’s Incantation (1897) stands as one of the most elaborate and symbolically charged posters of the celebrated Czech master. Commissioned by the Parisian printer F. Champenois, the lithograph measures approximately 140 × 60 cm and formed part of Mucha’s exploration of mystical and allegorical subject matter that followed his breakthrough theater work. In Incantation, Mucha fuses theatrical drama, mythic symbolism, and Art Nouveau ornament into a single, immersive composition. This analysis delves into the historical context, the artist’s evolving style, compositional structure, symbolic content, color and light treatment, line and ornament vocabulary, typographic integration, technical lithography, contemporary reception, and the work’s enduring legacy.

Historical Context and Commission

The late 1890s in Paris were marked by a fascination with the exotic, the mystical, and the theatrical. Sarah Bernhardt’s performances of La Mort de Socrate and L’Art de la Parole had showcased Mucha’s earlier posters, and the public appetite for dramatic imagery was growing. In 1897, Champenois commissioned Mucha to produce a series of decorative sheets—“Portfolio” prints—that would not advertise a specific play or product but would showcase the printer’s technical prowess and Mucha’s graphic vision. Incantation emerged as the centerpiece of this portfolio, offering a glimpse into the artist’s interest in myth, ritual, and the power of suggestion. Its title suggests a ritual utterance or magical invocation, promising viewers both visual enchantment and a touch of arcane mystery.

Mucha’s Evolving Style by 1897

By 1897, Mucha had solidified the hallmarks of his signature style: elongated female figures, sumptuous drapery, intricate floral halos, and sinuous “whiplash” curves. His earlier theater posters (1894–1896) emphasized bold contours and flat color fields, optimally suited to lithographic reproduction. With Incantation, Mucha merged these graphic strengths with more painterly modeling and layered ornamentation. The figure’s musculature and flesh are rendered with subtle shading rather than broad uniform planes; the background ornament recedes in delicate washes; metallic bronzes highlight selective details. Thus, Incantation represents a transitional work in which Mucha deepened his decorative complexity while maintaining the clarity and immediacy that made his posters so compelling.

Subject Matter and Narrative Ambiguity

Unlike his explicitly theatrical posters, Incantation offers no direct reference to a known drama or literary source. Instead, Mucha presents a ritual tableau: a towering maiden, her arms outstretched, stands above a hunched male figure weaving ribbons around a lyre or harp. Bowls of burning incense or ritual powders smoke at their feet. The maiden’s upward gaze and serene expression suggest invocation of unseen powers. The masculine figure’s bent posture and focused activity imply that he channels her invocation into sound or movement. By avoiding literal storytelling, Mucha encourages viewers to supply their own interpretations—whether invoking ancient rites, erotic enchantment, or the power of art itself.

Composition and Spatial Organization

Mucha arranges Incantation within an arched cartouche, echoing ecclesiastical windows and lending the scene a sacred or ceremonial aura. The central vertical axis features the maiden’s elongated form, balanced by the male figure’s crouched posture at the base. Diagonal lines—ribbons, drapery folds, and the lyre’s strings—create dynamic tension, guiding the eye upward from the ritual fires to the maiden’s raised arms. Surrounding ornamental motifs—interlacing vines, stylized flowers, and curling smoke trails—fill the negative space without overwhelming the figures. Horizontal bands above and below the arch reinforce the vertical pull, framing the scene and providing areas for potential text. Overall, Mucha achieves a harmonious unity of figure and ornament through rhythmic repetition of curves and careful balancing of mass.

Symbolic Content and Allegory

Incantation brims with symbolic references. The maiden wears a headdress of stylized peacock feathers—a symbol of immortality and the all-seeing eye—crowned by a circular halo that may represent the sun or the invocation itself. Her diaphanous gown suggests both vulnerability and transcendence. The lyre, associated with Apollo and Orpheus, signifies music’s magical power to move spirits. Bowls of smoking incense evoke ritual purification and the boundary between the earthly and the divine. The male figure’s bent posture hints at servitude or humility before a higher power. Collectively, these elements evoke the ancient marriage of music, ritual, and spiritual elevation—an “incantation” that transforms material into transcendent experience.

Color Palette and Light Treatment

Mucha’s palette in Incantation centers on warm earth tones—soft corals, muted ochres, olive greens, and creamy ivories—overlaid on wood‐pulp or wove paper with a warm base color. The maiden’s skin glows subtly against the metallic bronze highlights of her headdress and halo. The secondary figure is rendered in deeper rose and sienna, distinguishing flesh from drapery while maintaining tonal harmony. Translucent lithographic inks are layered to achieve gentle gradations, with the paper ground providing luminous highlights. Smoke trails and background ornament appear in lighter washes, receding to emphasize the central drama. Mucha’s holistic approach to color unifies figure, ornament, and text potential, enveloping the whole scene in a ritualistic glow.

Line Work and Decorative Vocabulary

At the core of Incantation is Mucha’s mastery of the sempiternal “whiplash” curve—a formal vocabulary that animates figure, drapery, and decoration alike. The maiden’s arms, the male figure’s drapery folds, the ribbons winding around the lyre strings, and the curling incense plumes all trace fluid, unbroken strokes. Floral motifs—possibly poppies or stylized water lilies—crowd the lower foreground in arabesque clusters. Vines and tendrils trace intricate, lace‐like networks behind the figures, their gold‐ink outlines lending the print a subtle gleam under lamplight. Mucha varies stroke weight to create depth: bold lines define silhouettes, while finer strokes articulate interior folds and botanical detail. The result is an integrated tapestry of undulating forms that both frame and sustain the central action.

Typography and Integration of Text Fields

While Incantation was issued as an image-only portfolio sheet, its arched format and decorative margins anticipate graphic posters that would include titles, credits, or announcements. The top and bottom edges feature horizontal linear bands that could accommodate lettering without disrupting the composition’s unity. Mucha’s custom letterforms—drawn from Slavic and Art Nouveau traditions—would likely have been woven into the border, mirroring the sinuous curves of the imagery. This strategic design foresight demonstrates Mucha’s commitment to integrating text and image—a principle that would come to define his later commercial work.

Technical Lithographic Process

Producing Incantation required the coordination of multiple lithographic stones, each carrying a separate color. Mucha first created a full-scale watercolor and pencil study, mapping out delicate gradations and ornamental details. That study was transferred—via pouncing or direct crayon transfer—to limestone plates (or zinc‐plates), with one plate per hue: lead‐white highlights, coral red, olive green, bronze metallic accents, and several intermediate tones. Printers used registration pins to align each pass precisely. Translucent inks allowed the warm paper ground to function as natural mid‐tones and highlights, reducing the need for opaque white. The final print emerges as a vividly textured tapestry rather than a flat graphic, showcasing the lithographer’s skill and Mucha’s painterly sensibility.

Reception and Contemporary Impact

Upon its debut, Incantation garnered praise in both artistic and journalistic circles. La Plume lauded it as “a summoning of the senses,” while Les Arts Décoratifs highlighted Mucha’s “alchemical fusion of form and ornament.” Though not tied to a specific theater engagement, the sheet circulated widely among collectors of decorative prints, art dealers, and upscale stationery shops. Its esoteric subject matter resonated with Symbolist currents in poetry and painting, and it further enhanced Mucha’s reputation as an innovator capable of transcending mere commercial illustration. The portfolio’s success prompted Champenois to commission additional mythic‐themed sheets and solidified Mucha’s status as a prime exponent of public‐facing fine art.

Influence on Graphic and Decorative Arts

Incantation extended Mucha’s impact beyond the realm of posters into interior decoration, jewelry design, textile patterning, and even architectural ornament. Its combination of mythic allegory and Art Nouveau flourish inspired tile mosaics, stained-glass windows, and wrought-iron gates in the fin-de-siècle style. In graphic design, the poster’s integration of figure and frame influenced Vienna Secession artists like Gustav Klimt, who adopted swirling backgrounds and symbolic female forms. Mucha’s decorative vocabulary—peacock feathers, incense bowls, ritual ribbons—echoed across the decorative arts, inspiring motifs in ceramics, bookbindings, and fashion illustration through the early 20th century.

Legacy and Preservation

Today, Incantation is recognized as one of Mucha’s most ambitious mythic compositions. Original lithographic proofs are held in museum collections—Musée d’Orsay (Paris), the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), and the Museum of Decorative Arts (Prague)—and occasionally appear in retrospectives of Art Nouveau. Conservators address issues of paper acidity, ink fading, and minor craquelure from handling, using deacidification treatments and reversible consolidants to stabilize surfaces. High-resolution facsimiles and digital renderings ensure broader public access, while Mucha’s original watercolor studies remain archival treasures for scholars examining his creative process.

Conclusion

Alphonse Mucha’s Incantation transcends the boundaries of theatrical advertisement, offering a richly layered vision of ritual, music, and mystical invocation. Through masterful composition, fluid linework, harmonious color, and symbolic depth, Mucha elevates lithographic poster art into a realm of poetic resonance. Its legacy—spanning Symbolist painting, decorative arts, and modern graphic design—attests to Mucha’s unparalleled ability to weave narrative, ornament, and emotion into a timeless tapestry. More than a hundred years after its creation, Incantation continues to captivate viewers with its evocation of arcane power and the transcendent potential of art.