Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

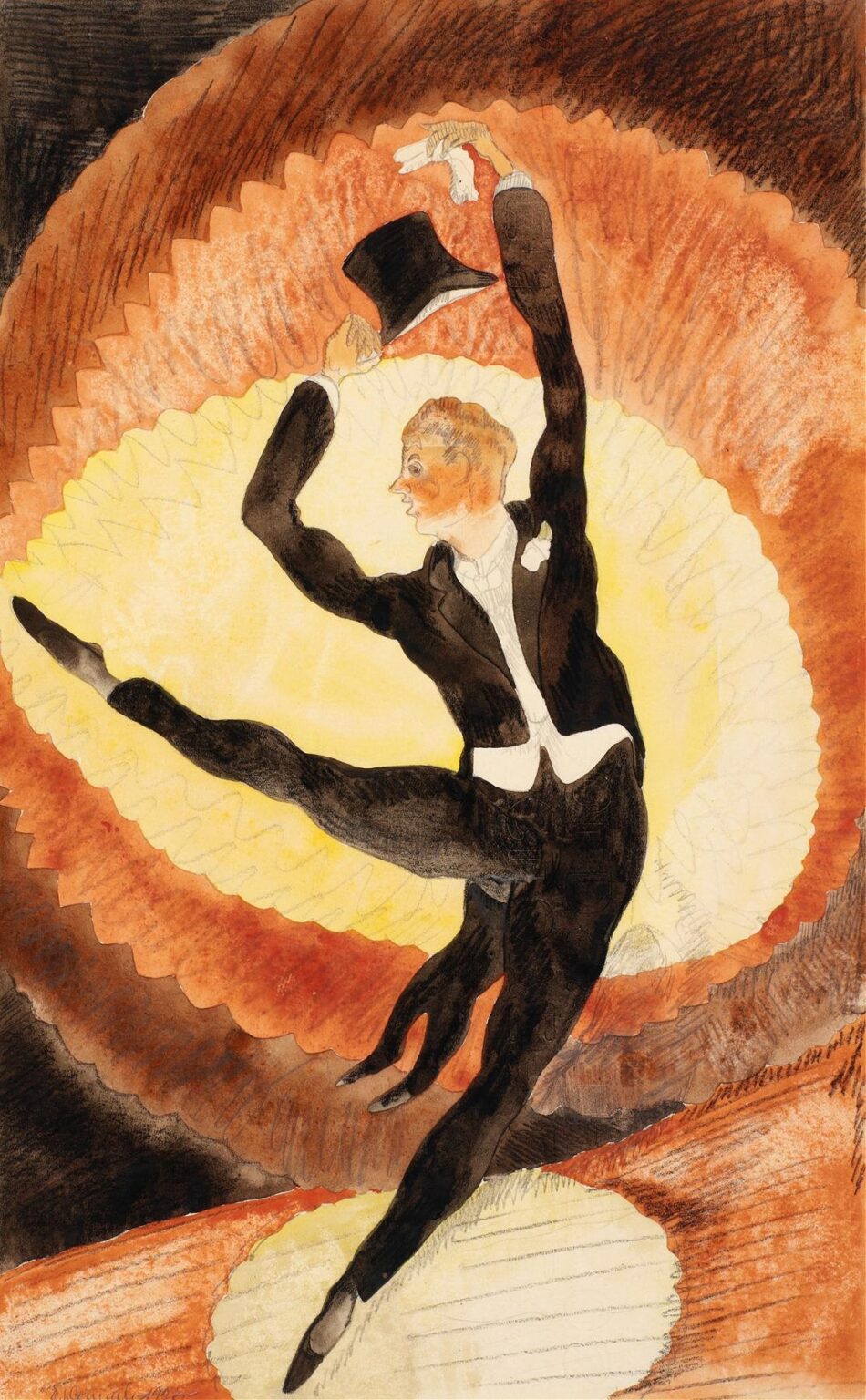

In 1920, Charles Demuth created In Vaudeville, Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat, a masterful watercolor and pencil work that captures the kinetic energy of performance through refined modernist forms. Departing from his more widely known precisionist industrial scenes, Demuth turns here to the theatrical world of vaudeville, focusing on the singular figure of an acrobatic dancer at the height of his leap. The painting’s seamless fusion of abstraction and figuration reveals Demuth’s unique approach: distilling motion into geometric rhythms while preserving human vitality. Through a detailed analysis of its formal elements, historical context, and symbolic resonances, we uncover how this work embodies the tension between balance and daring, reflecting both the spirit of popular entertainment and the innovations of early twentieth‑century avant‑garde art.

The Artist: Charles Demuth and His Late‑Career Modernism

Born in 1883 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Charles Demuth emerged as a central figure in American modernism by synthesizing European avant‑garde influences with indigenous subjects. After studies in Leipzig and Paris exposed him to Cubist and Fauvist experiments, Demuth returned to the United States intent on forging a style that emphasized precision of line and clarity of form. Although he is often celebrated for his stark urban and industrial landscapes—marked by clean edges and architectural regularity—he also devoted significant attention to depicting human performers and theatrical environments. By 1920, Demuth had honed a watercolor technique that married fluid washes with crisp pencil contours, enabling him to render both the solidity of objects and the dynamism of bodies in motion. This breadth of subject matter and technical mastery positions him as a versatile interpreter of modern life.

Historical and Cultural Context of 1920 America

The early 1920s in America were defined by postwar optimism, technological advancement, and the flourishing of popular entertainment. Vaudeville, a circuit of variety shows presenting acrobats, dancers, comedians, and magicians, captivated audiences across urban and rural venues. At the same time, modernist artists sought new means of expression that would break from nineteenth‑century traditions. Demuth’s choice to depict a vaudeville dancer in 1920 reflects this confluence of high and low culture. While newspapers and illustrated posters disseminated images of performers to a mass audience, avant‑garde painters pursued abstraction and formal experimentation. Demuth’s work bridges these worlds by elevating a commonplace subject—an acrobat’s leap—into a study of line, color, and spatial dynamics, emblematic of a society embracing both spectacle and innovation.

The Influence of Vaudeville on Demuth’s Vision

Vaudeville’s emphasis on display, rhythm, and surprise resonated deeply with Demuth’s aesthetic sensibilities. He was drawn to the discipline required of acrobats and dancers, whose controlled strength and geometric poses echoed his own commitment to compositional rigor. Photographs and lithographed theater programs likely informed his visual vocabulary, but Demuth transfigures these sources through abstraction. The stage becomes a flattened arena of shapes and color fields rather than a realistic setting, allowing the performer’s body to assert itself as both figure and form. Demuth’s engagement with vaudeville subjects reveals not only an interest in contemporary entertainment but also a fascination with movement as an organizing principle in art, aligning him with European contemporaries who celebrated dynamism in painting.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

In In Vaudeville, Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat, Demuth arranges the figure against a series of concentric curved bands that suggest both stage curtains and the halo of a spotlight. The central dancer is positioned on a simple platform rendered in oblique perspective, creating a subtle tension between flatness and depth. His extended leg projects diagonally across the composition, counterbalanced by the raised arm holding the top hat. Negative space—areas devoid of heavy pigment—provides breathing room and accentuates the bold arcs defining the circular backdrop. Through this choreography of shapes, Demuth guides the viewer’s eye along predetermined pathways: from the dancer’s pointed foot, upward along the sweeping curve of his torso, to the tip of the hat. The composition thus becomes an enactment of the dancer’s trajectory, translating movement into visual structure.

Line, Shape, and Form in “In Vaudeville, Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat”

Demuth’s pencil outlines articulate the contours of the dancer’s musculature and costume with a precision reminiscent of architectural drafting. These decisive lines intersect with broad watercolor washes that fill the forms without masking their angularity. The dancer’s limbs, though naturalistic in proportion, are abstracted into tapered cylinders and planar facets. His top hat, rendered in near‑solid black, contrasts with the softer hues of skin and costume, providing an anchor that balances the composition. Curvilinear shapes dominate the background, echoing the dancer’s arched pose and fostering a dialogue between figure and setting. Rather than relying on graduated modeling, Demuth defines volume through the interplay of line and flat color, achieving a sculptural effect through two‑dimensional means.

Color Palette and Light Interaction

The muted palette of ochre, burnt sienna, and slate gray imbues the painting with a warm yet restrained atmosphere, evocative of dimly lit theaters and gaslit auditoriums. Demuth’s watercolors range from translucent to richly saturated, allowing the paper’s whiteness to serve as both highlight and focal point—particularly on the dancer’s face, shirt cuffs, and portions of the stage. Subtle shifts in tone suggest curvature and depth without resorting to strong chiaroscuro. The concentric bands vary in intensity, the innermost yellow ring radiating outward into deeper russets and browns that frame the action. Light, therefore, is implied by these tonal progressions rather than by an explicit source. This approach reinforces the painting’s modernist leanings, privileging color relationships and compositional harmony over literal illumination.

Gesture and Movement Captured in Stillness

Paradoxically, the painting’s static medium conveys an acute sense of motion. The dancer’s airborne posture—legs akimbo, torso arched, top hat aloft—appears frozen at the apex of a leap. Fine pencil strokes trail behind the hat and at the dancer’s trailing foot, indicating trajectory and velocity. The sweeping arcs of the background amplify this dynamism, as if the environment itself responds to the dancer’s energy. Demuth’s economy of detail shifts emphasis away from facial expression and onto the overall gesture, inviting viewers to complete the action mentally. Each curve and diagonal line contributes to a rhythmic pulse that reverberates across the picture plane, transforming the watercolor into a visual echo of performance.

Symbolism and Theatricality in the Acrobatic Pose

Beyond its literal depiction of a performer, the painting may be read as an allegory of modernist ambition. The top hat, an emblem of elegance and showmanship, becomes a symbol of aspiration lifted skyward at the dancer’s fingertips. The concentric backdrop, reminiscent of both stage curtains and celestial orbits, situates the figure within a liminal space between earth and air, reality and illusion. This juxtaposition underscores the dual nature of vaudeville itself—a realm of spectacle that both entertains and unsettles, offering escapism while revealing the precarious balance of human endeavor. Demuth’s acrobatic dancer thus embodies the artist’s own leaps of faith into new aesthetic territories.

Psychological Undertones and Expressive Restraint

Despite the dynamic action, the dancer’s face remains composed, his features outlined with minimal shading yet animated by a slight turn of the head. This restraint suggests professional focus rather than unbridled exuberance. The viewer senses concentration underlying the performance: muscles taut, attention fixed. The muted background tones further reinforce a sense of quiet intensity, as if the world outside the spotlight has faded to neutrality. Demuth’s measured use of color and line here evokes the mental discipline required of performers—and, by extension, of artists—who must balance flair with precision. The painting thus operates on both a kinetic and contemplative level, inviting reflection on the inner conditions of creative practice.

Modernist Synthesis: Bridging Avant‑Garde and Popular Entertainment

Charles Demuth’s rendering of a vaudeville dancer in a modernist idiom exemplifies the cross‑pollination between fine art and mass culture that characterized much of early twentieth‑century innovation. While Cubists fragmented reality and Futurists celebrated mechanized speed, Demuth found in live performance a source of organic movement and immediacy. His painting does not mimic photographic realism, nor does it fully dissolve form into abstraction; instead, it navigates a middle path, maintaining legible figures even as it simplifies them into fundamental geometric patterns. This synthesis resonates with a broader modernist ambition: to honor the vitality of everyday life while advancing a vocabulary of shape, color, and line that redefines pictorial tradition.

Technical Execution and Medium Mastery

Executed on paper, Demuth’s watercolor reveals an intimate dialogue between brush and pencil. The artist’s confident pencil lines serve as structural scaffolding, while washes of pigment glide over the surface with varied opacity. Demuth employs wet‑on‑wet techniques to achieve soft transitions in the background, contrasting with crisp, dry‑brush applications on the dancer’s garments. The interplay of transparency and solidity underscores his command of watercolor, a medium often considered capricious yet here handled with apparent ease. The small scale of the work encourages close viewing, rewarding observers who attend to subtle interactions of pigment and line. This technical fluency enables Demuth to capture both the drama of performance and the quiet sophistication of modernist design.

Place within Demuth’s Oeuvre and Vaudeville Series

While Demuth’s industrial and landscape paintings garnered critical acclaim, his vaudeville series remains a vital yet underappreciated facet of his career. In Vaudeville, Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat sits alongside other performance‑themed works from the late 1910s and early 1920s, in which dancers, jugglers, and actors populate stylized stages. Together, these paintings reveal Demuth’s fascination with the human figure as a vehicle for exploring rhythm, balance, and form. They also testify to his willingness to engage with popular culture during a period when many artists sought to break free from solely academic subjects. In retrospect, the dancer piece illuminates Demuth’s versatility and his role in expanding American modernism beyond architectural and industrial motifs.

Conclusion

In Vaudeville, Acrobatic Male Dancer with Top Hat encapsulates Charles Demuth’s ability to fuse modernist abstraction with the palpable thrill of live performance. Through meticulous line work, harmonious washes, and a dynamic composition, he transforms a fleeting theatrical moment into a resonant visual form. The painting’s interplay of balance and motion, restraint and exuberance, speaks to broader themes of artistic risk and creative innovation in postwar America. As part of Demuth’s vaudeville series, it stands as both a singular homage to popular entertainment and a testament to the artist’s enduring exploration of form in motion.