Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

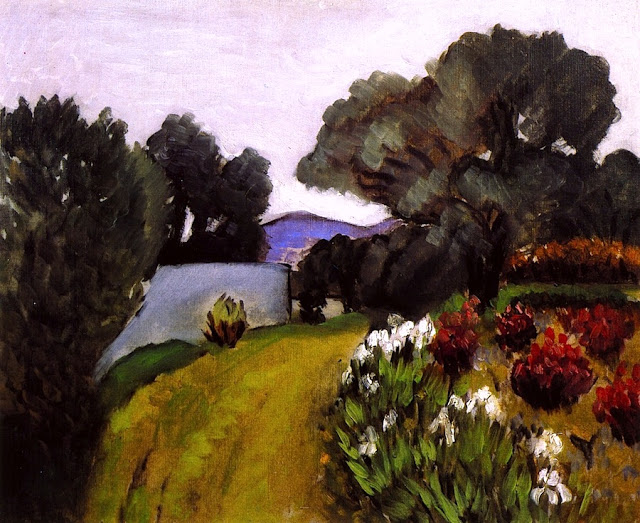

“In the Nice Countryside, Garden of Irises” (1919) is Henri Matisse’s clear, generous vision of the Mediterranean landscape at walking distance. A band of path lifts through turf the color of new olive oil; a low white wall breaks the greenery like a breath; heavy, sea-breeze trees lean inward; and on the right a deep border of irises and flowering shrubs burns in claret, rust, and creamy white. Beyond the trees a lavender ridge of hills floats under a pale sky. The scene feels both immediate and composed, as if Matisse had distilled several minutes of looking into a single, stable chord. Nothing is fussy, nothing is theatrical. Instead, color builds the space, brushwork records the air, and the garden becomes a stage where pattern and nature strike a poised, modern harmony.

The Nice Period Setting

Painted in the first full year after World War I, this canvas belongs to Matisse’s early Nice period, when the artist rebuilt his pictorial world around interiors, balconies, and close-knit landscapes. He exchanged prewar shock for equilibrium, cultivating a language where measured color relations replaced demonstrative bravura. The Mediterranean climate—steady, marine, and humane—suited that ambition. It softened shadows, cooled the sky into pearl and violet, and let blues and greens breathe instead of blaze. In these years Matisse painted nudes on pink couches, women with parasols on balconies, still lifes with lemons, and several outdoor gardens. “In the Nice Countryside, Garden of Irises” gathers that whole vocabulary outdoors: shallow, inhabitable space; decorative rhythm embedded in nature; and a palette tuned to warmth without heat.

First Impressions and Motif

At first glance the painting reads as a procession from left to right. Darker shrub masses hold the left edge, a low white garden wall interrupts the green, a path rides along a luminous strip of grass toward a stand of trees, and the right half bursts into bloom with iris leaves and crimson flower heads. Behind the trees the hills of Provence step back in graded violets, and the sky hovers pale and even. The motif is archetypal for the outskirts of Nice: cultivated border, clipped lawn, native trees, distant mountain. Yet Matisse refuses the postcard; he makes each element do structural work. The path sets the tempo, the wall resets the eye, the trees behave like columns, and the flowers provide color counterpoint that keeps the whole chord resonant.

Composition as Directed Walk

The composition is a choreographed walk. A curving green band enters at lower left and swings toward the center; this is both path and light, a strip of brightness that carries the viewer forward. The white wall acts as a hinge where the green turns. To its right the border of irises rises like a choir, their leaves pointed and rhythmic. Above, a canopy of broad, blue-green trees leans in from the right, pulling the space inward rather than letting it spill outward. The far hills form a long, slow triangle that rests against the trunk masses. The frame crops decisively—tops of trees, left shrubs, and the iris bed—so the scene feels close, as if you could reach down and touch leaf tips.

Color Architecture and Temperature

Color supplies the architecture. The ground is laid in three principal greens: a warm, yellowed green for sunlit path and upper lawn; a cooler, shadowed green under the trees; and a deep, blue-leaning green that locks the left mass. Trees are built from olive, slate, and peat, with warm umber veining where branches turn into light. The flowers on the right flare into saturated reds and russets, balanced by the white of iris blooms and small lights in the border behind them. A single thin violet band between trees and sky proposes distance without spectacle. The sky itself is a pale gray-violet, milked with white so that nothing glares. Because each color family returns across the painting, harmony is inevitable: the violet hill resonates with cools in the trees; the white wall answers the whites in iris and sky; the warm green at center echoes through the border’s yellow undertones. The palette is limited and relational, which is why the garden feels composed rather than cataloged.

Light and Atmosphere

The light is generous but steady. It falls from above, tucked behind thin high cloud, so that edges glow and broad planes breathe. There are few sharp shadows; modeling is achieved through temperature, with warmer greens rising on the path and cooler greens gathering under leaves. The white wall is not a sun-bleached glare but a parchment tone that catches the day’s softness. The atmosphere is recognizably Mediterranean, more sea-breeze than noon blaze, the kind of light that invites an unhurried stroll and allows color to speak at a comfortable volume.

Brushwork and Material Presence

Matisse paints the living textures of this garden without laboring them. The trees are knotted from short, juicy planes, some dragged nearly dry so the canvas weave breaks through, others loaded and buttery to build volume. The path and lawn are swept with elastic strokes that change direction as the turf bends. The iris leaves are flicked upward with quick, narrow marks; the crimson blooms are built from compact, rounded touches that sit up in relief. The white wall is pulled flat with broad, even passes that differentiate plaster from foliage. Everywhere, the evidence of the hand remains. The surface is honest about its making, and that candor keeps the garden present-tense.

Space: Shallow, Breathable, Modern

Depth is compressed by design. Overlap cues recession—border before lawn, lawn before trees, trees before hills, hills before sky—but linear perspective is minimal. The horizon is high. The large trees lean inward, keeping the eye on the near and middle distances. This controlled shallowness is a signature of the Nice period: it preserves the surface where color relations live while still offering a believable place to move. You inhabit this garden as you would one of Matisse’s interiors—you cross a patterned floor to a window, only here the floor is a band of turf and the window a slit of violet hill.

The Irises: Decorative Rhythm Grounded in Botany

The title calls out the irises, and Matisse paints them as both plant and pattern. Their leaves are tidy spears, splayed and stacked so the bed reads like a deck of cards fanned into green. White irises break into soft, petalled lights, while deeper red shrubs beyond add weight. The effect is ornamental without falsifying botany. In the Nice pictures, decoration is never something added after the fact; it is structural. Here the iris bed gives the right half a visual beat that answers the left mass of shrubs and the middle vault of trees. Pattern functions as architecture, keeping nature legible and musical.

The White Wall: Pause and Measure

The low wall is a small but indispensable device. It interrupts the green with a rectilinear pause, preventing the garden from becoming a single sweep. Its pale face provides a value scale for all other tones: lighter than turf, darker than sky, warmer than white iris. Pictorially it is the comma that allows the sentence to continue with clarity. Psychologically it signals the human presence that has tended the border, cut the path, and planted trees—quiet evidence of care rather than an anecdotal subject.

Trees as Columns of Air

The trees are not described leaf by leaf but conceived as columns of air. Their edges are darkened with elastic lines that tighten and loosen like pen strokes; inside those borders, planes of olive and slate toggle, suggesting a depth of foliage and the swell of wind. Matisse uses the trunks to triangulate space: one major trunk leans in from the right, two dark masses stand behind the wall, and a soft wedge of canopy rounds the left. They behave as architectural piers, holding up the pale sky and keeping the garden from flying apart.

Rhythm and the Viewer’s Walk

The painting teaches you how to walk it. Begin at the lower left where the path brightens; drift along the green band toward the white wall; pause there, then turn right into the iris bed where quick vertical strokes tick like metronome marks. Lift with the tree vault, let your gaze fall into the violet hills, then slide back through the soft sky to the left shrubs. Each circuit repeats—green to white to red to violet to pale—until the garden’s pulse becomes audible. This is the promenade pace that Matisse cultivated after the war: measured, attentive, sustainable.

Dialogue with Tradition

The canvas speaks to a long line of French gardens—from the intimate parks of Corot to Cézanne’s orchards—while remaining unmistakably Matisse. Like Corot, he trusts cool atmospheres and human scale; like Cézanne, he builds volume from color planes rather than from descriptive outline. But he goes further in integrating decorative rhythm into the landscape itself. The iris bed is kin to the striped tablecloths and lattice floors of his interiors; the trees echo the arabesques that will later populate the cut-outs. Tradition provides the frame, and Matisse re-scores it in his key.

A Postwar Ethics of Clarity

Painted in 1919, the picture’s quiet order reads as an ethic as much as a style. Nothing is excessive; everything is proportioned to its neighbors. The palette is restrained; the space is walkable; the forms are simplified to what they must be. In place of heroic gestures, Matisse offers durable relations. The garden holds together because color is tuned, edges breathe, and intervals are respected. That clarity—local, domestic, unboastful—was a kind of repair after years of rupture.

Comparisons within 1919

Seen beside “The Promenade,” this garden is warmer and more cultivated; compared with “Landscape, Nice,” it is more saturated and architected by horticulture. All three share the high horizon, the shallow depth, the reliance on temperature shifts over shadows, and the visible hand. But here the iris bed gives a particular swing to the right half of the canvas, and the white wall introduces a geometric calm that the blossom orchards do not need. It is the outdoor counterpart to his studio still lifes with lemons and flowers: ordinary forms set in an interval that lets color speak.

Material Choices and Painterly Economy

The materials are traditional, handled with thrift and purpose. Lead white builds the wall and iris lights; earth greens, ochres, and umbers structure turf and trunks; ultramarine and a touch of carmine lean the hills toward violet; ivory black sharpens edges in key places. Paint is thicker where light needs to stand up—in petals and highlights—and thinner where atmosphere must breathe—sky, distant hill, shadowed lawn. The economy of means keeps the surface lucid and the harmony audible.

How to Look Today

Approach the picture slowly, as you would the real border after a rain. Stand close enough to see brush ridges along a crimson bloom and the dry drag of a green stroke across canvas tooth. Step back until the border fuses into a single living band. Notice how the path’s yellow-green lifts your eye, how the wall’s cool white resets it, how the trees’ shadow cools the temperature, and how the lavender hills rinse the space with distance. Resist the urge to search for anecdote; let the relations do the talking.

Lasting Significance

“In the Nice Countryside, Garden of Irises” endures because it turns an ordinary garden moment into a complete order of seeing. It proves that pattern can be structural without smothering nature, that shallow space can still invite inhabitation, and that a limited palette can carry rich sensation. In doing so it clarifies the Nice period’s central promise: a modern art grounded in hospitality, where color, air, and human pace are kept in balance.

Conclusion

Matisse’s garden is not a transcript but a design that feels true. A path of warm green, a quiet white wall, a vault of olive trees, a right-hand choir of irises, and a rinsed lavender horizon are arranged with such care that they become inevitable. Color builds the architecture, brushwork records the climate, and pattern supplies rhythm. The result is a painting that offers, then and now, the restorative pleasure of moving through a world ordered by attention rather than noise. It invites the viewer to walk more slowly, to look more steadily, and to trust that clarity can be a form of joy.