Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

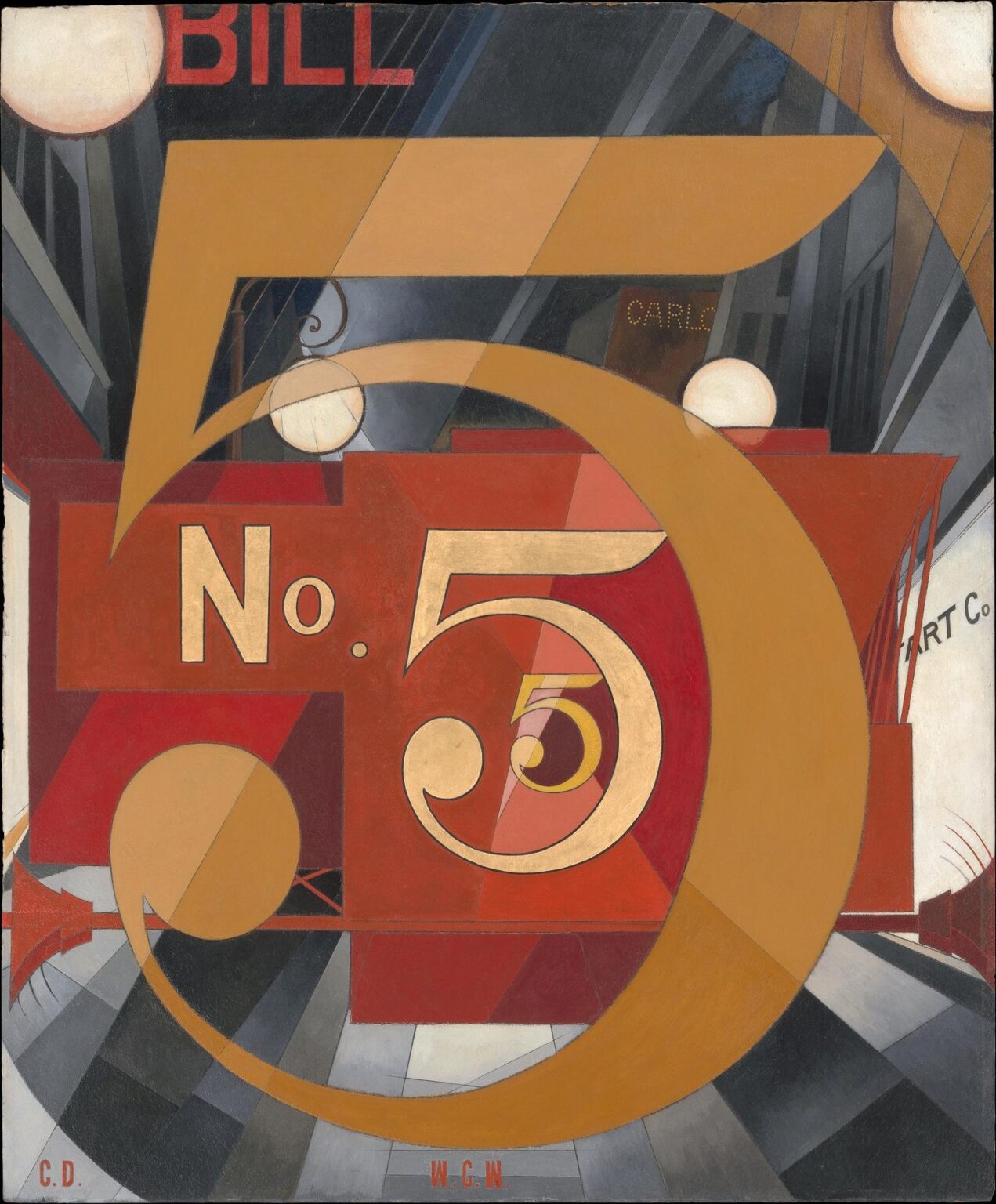

Charles Demuth’s I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928) stands as one of the most iconic works of American Precisionism, fusing rhythmic typography, bold color, and fractured geometry to create a visual poem that resonates with both literary homage and modernist innovation. Inspired by William Carlos Williams’s poem “The Great Figure,” which recounts the poet’s experience of glimpsing a fire engine numbered “5” racing through the city streets, Demuth transforms this fleeting image into a complex compositional symphony. The painting captures the roar of machinery, the flash of headlights, and the pulse of urban life, distilling them into overlapping forms, vibrating color fields, and repeated numeral motifs. Through an analysis of its historical roots, formal architecture, color dynamics, typographic interplay, thematic depth, and technical execution, we will explore how I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold transcends mere representation to become a landmark of American modernism.

Historical and Cultural Context

The late 1920s marked a period of fervent experimentation in American art, as artists sought to forge a distinctive national voice distinct from European avant‑garde movements. Demuth, born in 1883 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, had studied in Leipzig and Paris, absorbing lessons from Cubism’s fragmentation, Futurism’s dynamism, and the geometric abstraction emerging across Europe. By 1928, he had become a pivotal figure in Precisionism, alongside Charles Sheeler and Georgia O’Keeffe, emphasizing clear, sharply defined forms and the iconography of modern life—skyscrapers, bridges, factories. Meanwhile, William Carlos Williams, a close acquaintance of Demuth’s, published “The Great Figure” in Horizon magazine the same year. The poem’s urgent tercets—“Among the rain / and lights / I saw the figure 5 / in gold / on a red / firetruck”—captured the visceral immediacy of a city moment. Demuth’s painting serves as both an artistic translation of Williams’s verse and a testament to the cultural cross‑pollination between poetry and the visual arts during the interwar years.

Composition and Spatial Architecture

At the heart of I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold lies a deft orchestration of overlapping geometric shapes, converging lines, and repeated motifs. The canvas is dominated by five concentric iterations of the gold numeral “5,” each decreasing in size as it recedes into a deep red field at the center. These numerals form a swirling vortex that seems to rotate and pulse, evoking the sensation of a speeding firetruck. Behind and around the “5”s, Demuth constructs a layered background of angular forms—black and gray rectangles suggest tall buildings or rainswept streets, while muted lavender and blue planes imply atmospheric depth. Radiating lines from the top corners arc toward the center, reminiscent of headlights cutting through night rain. This dynamic interplay of forward‑thrusting shapes and receding planes creates a palpable sense of movement and urgency, compressing time and space into a single vibrant moment.

Color Dynamics and Emotional Resonance

Color operates as a primary conveyor of emotion and movement in this work. The painting’s palette revolves around a vivid scarlet that consumes the central field, punctuated by the warm, metallic gleam of gold leaf on each numeral “5.” The gold provides a luminous contrast—shimmering against the matte red and suggesting the glare of firetruck lights. Surrounding this core, Demuth deploys a cooler spectrum of charcoal grays, deep blues, and soft purples to evoke the rain‑slicked urban environment at night. Subtle splashes of white in the four circular “lamps” (top corners and flanking the red background) reference streetlights or headlights, their pearly intensity cutting through the dark. Through these calculated color juxtapositions—warm versus cool, matte versus metallic—Demuth captures both the tangible and psychological impact of the firetruck’s passage: alarm, awe, and the fleeting beauty of mechanical power.

Typographic Integration and Graphic Design

Distinctive among Precisionist works, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold elevates typography to a central compositional element. Demuth meticulously rendered the “No.” in cream‑colored uppercase letters to the left of the central 5, reinforcing the notion of an official designation. The letters “C. D.” in the lower left corner and “W. C. W.” at the bottom center pay direct homage to the artist and the poet, respectively, blurring boundaries between artistic and literary authorship. The styling of the numerals—bold serif forms with graceful curves—echoes the signage and graphic design found on contemporary vehicles and advertisements. By integrating typographic elements as pictorial forms, Demuth not only underscores the modern world’s merchandising and mechanization but also celebrates the graphic arts as a valid medium for fine art. The result is a seamless fusion of drawing, painting, and design.

Line, Rhythm, and the Illusion of Speed

Lines radiating from the outermost layers of the numerals generate a sense of acceleration. Demuth’s use of parallel strokes—both in the background and around the numeral rings—mimics the visual blur of motion, as if the viewer’s gaze were fixed on the fire engine while the world streams past. These lines, angled and varied in width, suggest raindrops slashing across headlights or the tracks of the truck’s tires on wet pavement. The concentric repetition of the “5” amplifies the sensation of echoing sound—five successive bell rings or drumbeats—reinforcing the multisensory impact of the scene. Thus, line and rhythm collaborate to convey speed, sound, and the fleeting nature of the urban encounter.

Technical Execution and Mixed Media

Demuth executed I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold in oil and gold leaf on composition board, a departure from his predominantly watercolor practice. The stiff board allowed for the crisp edges and hard‑edged polygonal shapes that define the composition. Layers of oil paint were applied with extraordinary precision—blocks of color are flat and uniform, free of visible brushstrokes, while the gold leaf motifs gleam with reflective vibrancy. Fine pencil or charcoal lines may underpin certain edges, though they are largely subsumed by paint layers. This technical approach aligns with the Precisionist aim of “machine‑like” finish, yet the inclusion of gold leaf introduces an artisanal element that contrasts with the otherwise industrial aesthetic. The result is a work that oscillates between the hand‑made and the mechanical, reflecting the tension at the heart of modern life.

Literary Dialogue and Visual Translation

I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold exists in explicit dialogue with William Carlos Williams’s poem. Demuth’s concentric circles of numerals mirror the poem’s rhythmic structure: the repeated lines “I saw the figure 5 in gold” functioning as visual leitmotif. The placement of “W. C. W.” beneath the composition acknowledges Williams’s authorship, while the painting itself interprets the poem’s sensory detail—rain, lights, motion—through visual means. This cross‑disciplinary fertilization exemplifies the early twentieth century’s collaborative spirit among poets and painters, particularly within the circle of avant‑garde New York artists and writers. The work invites viewers to read image as text and text as image, underscoring the shared concerns of modernist experiments across media.

Thematic Undercurrents: Modernity and Memory

Beneath its formal bravura, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold probes themes of modernity, memory, and the fleeting nature of experience. The fire engine, a symbol of emergency and collective protection, speeds through the city—an embodiment of technological progress and communal vigilance. Yet Demuth’s abstracted representation distances us from literal narrative, prompting reflection on how we recall and reconstruct sensory events. The repeated numeral motif suggests the persistence of memory: one imprint upon the mind repeated like an echo. The tension between foreground action (the golden “5”s) and receding geometric planes evokes layered consciousness—the moment of seeing and the mind’s subsequent layering of impressions.

Relation to Demuth’s Precisionist Oeuvre

While many associate Demuth with his later works featuring factory smokestacks, bridges, and signage, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold holds a special place within his oeuvre. It synthesizes his interests in typography (as seen in works like Poster-Pennsylvania Railroad), Cubist‑derived fragmentation, and the celebration of American industrial iconography. Unlike the imposing stillness of a manufacturing plant, this painting captures dynamic movement, yet the formal discipline remains consistent: clear edges, simplified geometry, and a luminous surface. It represents a zenith of Demuth’s Precisionist achievements, demonstrating that the modern world’s machinery—whether static or in motion—could be rendered with equal elegance and subtlety.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Upon its exhibition, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold garnered acclaim for its originality and technical finesse. Critics noted the painting’s successful translation of poetic imagery into a self‑sufficient visual composition. Over subsequent decades, it has become emblematic of American modernism, studied in art history courses alongside works by Georgia O’Keeffe, Charles Sheeler, and Stuart Davis. The painting’s legacy extends beyond Demuth himself, influencing graphic designers and fine artists who explore the interplay of text and image, the abstraction of motion, and the integration of metal leaf into painting. Today, it remains Demuth’s most celebrated masterpiece, a focal point of the Whitney Museum’s collection and a touchstone for interdisciplinary creativity.

Viewer Engagement and Interpretive Openness

Despite—or perhaps because of—its precise graphic presentation, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold invites open-ended interpretation. Viewers may appreciate its formal qualities: the harmony of red and gold, the elegance of the numeral curves, the dynamic spatial composition. Others may recall Williams’s poem, listening mentally for the imagined rumble of the firetruck bells. Still others might view the work as a meditation on time and memory, contemplating how a single visual flash can reverberate in the mind. The painting’s capacity to accommodate multiple readings—visual, literary, emotional—attests to its enduring power and Demuth’s success in merging poetry and painting into a unified modernist statement.

Conclusion

Charles Demuth’s I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold (1928) remains a landmark of American art, encapsulating the Precisionist ethos through its bold typography, geometric harmony, and evocative color. Rooted in William Carlos Williams’s poetic vision, the painting transcends literal narrative to become a visual symphony of motion, light, and memory. Demuth’s meticulous technique—oil and gold leaf on board—coupled with his sophisticated compositional design, elevates a simple urban encounter into a timeless exploration of modern life. As both a tribute to a literary friend and a masterpiece of visual abstraction, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold continues to captivate and inspire, its golden figure ringing out across decades as a testament to the radiant possibilities of form, color, and interdisciplinary collaboration.