Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

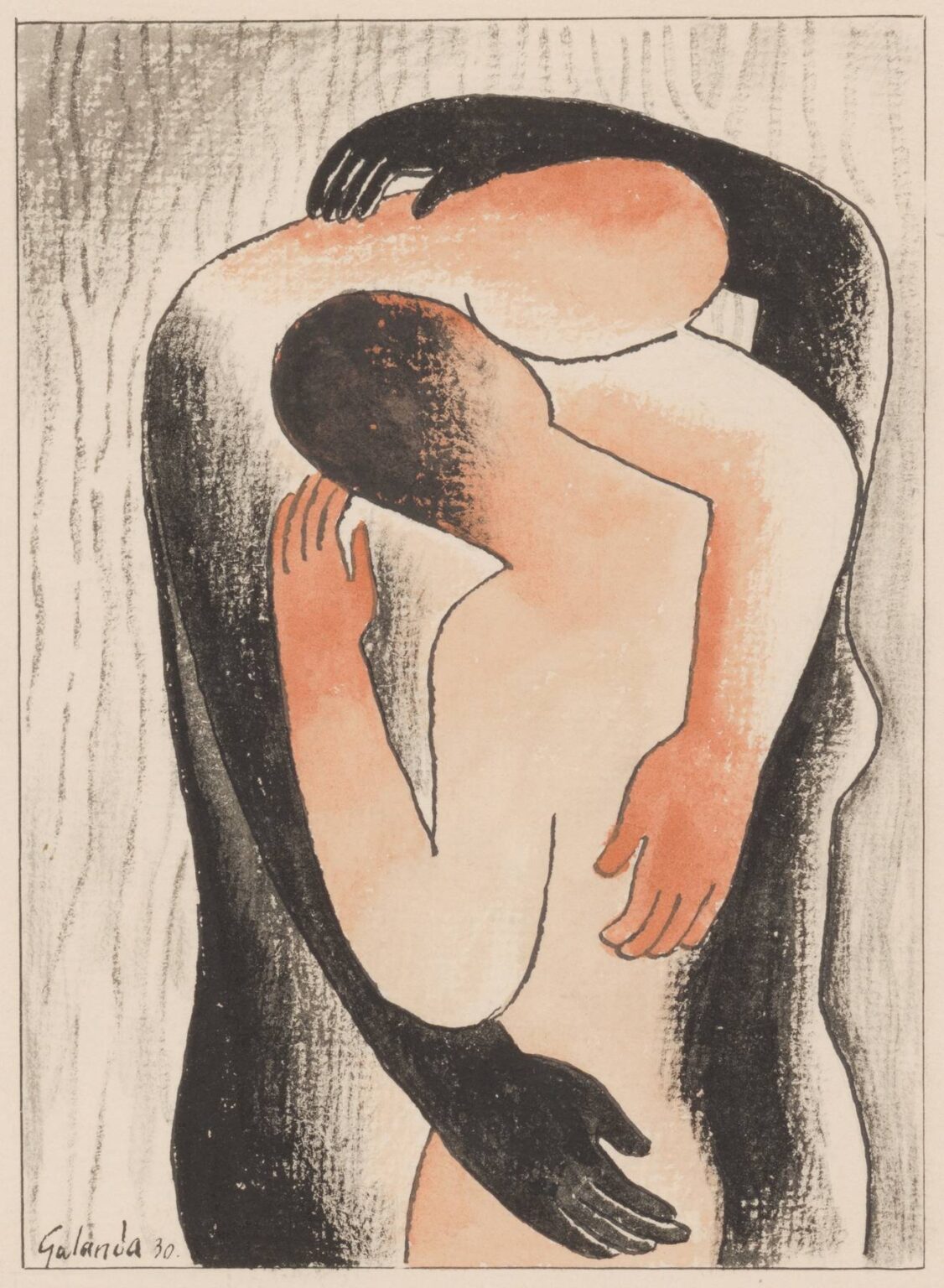

Mikuláš Galanda’s Hug (1930) stands as a testament to the artist’s ability to distill profound human emotion into a deceptively simple visual vocabulary. At first encounter, one sees two abstracted figures—one bathed in a warm peach tone, the other in deep charcoal—locked in an embrace that transcends mere physical contact to become an emblem of psychological intimacy. The painting’s pared‑down forms, seamless line work, and strategic use of color invite viewers to contemplate the universal themes of protection, vulnerability, and mutual reliance. In extending this analysis to its fullest, we will journey through the painting’s historical context, Galanda’s artistic evolution, formal strategies, symbolic depth, technical craftsmanship, cultural resonance, reception history, and ongoing legacy. Through this exploration, Hug emerges not only as a pivotal work within Galanda’s own oeuvre but also as a landmark in the broader narrative of Slovak modernism and European avant‑garde art.

Historical and Cultural Context

The year 1930 in Czechoslovakia was defined by the exhilaration and anxieties of a young republic forging its identity amid shifting political tides in Europe. Having gained independence in 1918, Czechoslovakia experienced rapid industrialization, urbanization, and cultural flux. Artists and intellectuals found themselves negotiating between the pull of nationalist sentiment—celebrating folk traditions, rural life, and Slavic heritage—and the push of international modernist movements such as Expressionism, Cubism, and Surrealism. Mikuláš Galanda, a key figure in Bratislava’s avant‑garde circles and co‑founder of the Nová Trasa (New Path) group in 1928, stood at this crossroads. He championed art that was both regionally rooted and formally daring, seeking to communicate directly with diverse audiences. Hug emerges from this context as both a personal statement on human connection and a broader cultural assertion that empathy and solidarity can transcend social upheaval.

Mikuláš Galanda’s Artistic Evolution

Galanda’s journey from academic draughtsman to pioneering modernist traversed diverse geographic and stylistic territories. Born in 1895, he trained at the Hungarian Royal Academy in Budapest, where he mastered classical draftsmanship before encountering the innovations of the Vienna Secession and German Expressionism during study trips to Munich and Vienna. Returning to Bratislava, he initially produced richly colored easel paintings and folk‑inspired woodcuts. By the mid‑1920s, he had gravitated toward graphic media—woodcut, lithography, pen‑and‑ink—seeking greater clarity of form and economy of means. The founding of Nová Trasa in 1928 marked his public commitment to a national modernism blending folk motifs with European avant‑garde. In the years that followed, Galanda’s style matured into a fusion of linear precision and poetic abstraction, epitomized by works such as Landscape with a Chair (1930) and culminating in deeply human works like Hug. Through this evolution, he demonstrated that raw emotional power can emerge from the simplest compositional gestures.

Formal Composition and Spatial Dynamics

In Hug, Galanda constructs a compact yet dynamic composition anchored by the meeting of two bodies. The embrace forms a continuous loop: the charcoal figure’s arm arcs protectively around the peach figure’s shoulders, while the latter’s arm returns the gesture, completing an unbroken circle. This cyclical geometry symbolizes the reciprocity of care. Negative space frames the figures on all sides, intensifying their isolation and underscoring the primacy of interpersonal connection. Rather than situating them in a detailed environment, Galanda allows the blank background to function as a universal stage, evoking any place where human vulnerability meets compassionate touch. The scan of contour lines that define the figures abandons perspectival depth, instead favoring a flattened plane that heightens intimacy and directs focus to the embrace itself.

Line and Contour

Line serves as the painting’s animating principle. Galanda’s contours are drawn with unwavering confidence: thick, rhythmic strokes outline the bodies, while subtler hatchings suggest the gradations of flesh and shadow. The charcoal figure’s edges are textured with stippled shading reminiscent of woodcut, a nod to Galanda’s printmaking past. The peach figure, by contrast, is rendered with softer, smoother lines, mirroring the warmth and vulnerability it represents. Where the two figures meet, the linework blends—seemingly a single line tracing two distinct bodies—symbolizing unity without erasing individuality. This masterful modulation of line weight and texture creates an almost musical rhythm, carrying the viewer’s gaze around the embrace in a continuous, comforting flow.

Color Palette and Tonal Contrast

Galanda employs a remarkably restrained palette to maximum emotional effect. The warm peach tone of one figure evokes human flesh, warmth, and openness, while the deep charcoal of the other suggests solidity, protection, and the unknown. The transition between these two hues is mediated by subtle overlays of gray, creating soft transitional zones where identity and emotion blur. This dual‑tone approach achieves harmony through contrast: the figures are distinct yet inseparable, their colors complementing one another like two halves of a single chord. By eschewing additional colors, Galanda focuses the viewer’s attention on the nature of the embrace, allowing color to function as a direct conduit for conveying the psychological states of trust and support.

Symbolism and Emotional Resonance

At its core, Hug is a meditation on the human need for empathy and the transformative power of compassionate touch. The protective charcoal figure can be read as a guardian—parent, friend, or perhaps an abstract representation of humanity’s better impulses—while the peach figure embodies the recipient of comfort. Their intertwined arms form a shield-like shape, suggesting that in union lies safety. The absence of detailed facial features democratizes the painting’s message: any viewer can see themselves in either role. In a Europe grappling with economic hardship and political fragmentation, Hug served as a potent symbol of resilience through solidarity. Its emotional resonance extends beyond its era, reminding contemporary audiences that human connection remains our most enduring refuge.

Technical Execution and Mixed Media Techniques

Although Hug appears painterly, its textures and shading betray Galanda’s graphic training. The charcoal figure’s stippled surface echoes woodcut mark‑making, while the peach figure’s smooth washes resemble gouache or egg tempera. The line contours, with their unwavering clarity, hint at pen or fine brush. Galanda’s hybrid technique—merging printmaking sensibility with painterly color application—exemplifies his commitment to cross-disciplinary artistry. The paper ground, visible through the lighter washes, contributes to the work’s luminosity, suggesting that absence of pigment can be as meaningful as its presence. This technical synthesis underscores Galanda’s belief that mastery lies not in rigid medium boundaries but in the seamless integration of expressive tools.

Relation to Slovak Folk Traditions

While Hug resonates with European avant‑garde abstraction, it also draws upon Slovak folk iconography, particularly the motif of intertwined dancers and communal rituals. Folk embroidery patterns frequently depict repeated loops and circles, symbolizing eternity and collective bonds. Galanda’s embrace replicates this visual language, translating the interlocking motifs of peasant textiles into a modern idiom. The painting thus bridges folk heritage and contemporary form, reaffirming the relevance of traditional symbols in a rapidly changing world. By grounding avant‑garde techniques in cultural memory, Galanda crafted a national modernism that spoke authentically to Slovak audiences while remaining conversant with broader artistic currents.

Psychological and Anthropological Dimensions

Beyond its immediate visual impact, Hug engages with deeper psychological themes. The act of hugging triggers the release of oxytocin, fostering feelings of trust and reducing stress—biological realities mirrored in Galanda’s composition. Anthropologically, embrace rituals appear across cultures as potent symbols of reconciliation, alliance, and social cohesion. Galanda’s painting distills these complex human behaviors into a singular, potent image, demonstrating how art can capture the essence of universal human rituals. Viewers may project personal memories of embrace—comfort in times of grief, joy in reunion—onto the painting, creating a dynamic, empathetic dialogue between artwork and audience.

Exhibition History and Critical Reception

Hug first appeared in Galanda’s 1930 solo exhibition in Bratislava, where critics lauded its emotional directness and formal economy. The painting traveled to Prague and then to key Central European exhibitions focused on modernist and graphic arts. Critics highlighted its unique fusion of printmaking aesthetics with painterly color, praising Galanda’s ability to evoke complex feelings without narrative elaboration. In subsequent decades, Hug featured prominently in retrospectives of Slovak interwar art, often cited as a landmark of the era’s humanistic turn within modernism. Its international visibility grew through traveling exhibitions on European avant‑garde, establishing Galanda’s reputation as a significant, if under‑recognized, figure beyond national borders.

Place Within Galanda’s Oeuvre

While Mikuláš Galanda produced many drawings, prints, and paintings exploring figure and landscape, Hug occupies a special place as the apex of his figural abstraction. Earlier works featured folk scenes and narrative content, while later pieces sometimes ventured into decorative pattern or pure abstraction. Hug, however, synthesizes his graphic calligraphy, printmaking textures, and psychological insight into a singular, iconic motif. It encapsulates his commitment to reducing form to its expressive essentials, demonstrating how a single gesture can carry the weight of universal human experience. In this sense, the painting serves as both a culmination of his earlier explorations and a keystone for his legacy.

Legacy and Contemporary Resonance

Decades after its creation, Hug continues to inspire artists and scholars. Contemporary painters draw upon its minimal forms and emotional clarity, exploring themes of vulnerability, care, and social solidarity. Graphic designers reference its interplay of line and color, seeking similarly direct modes of communication. In therapeutic and social practice contexts, the painting has been used as a visual prompt for discussions around empathy and human connection. Museums and galleries feature Hug in exhibitions on the history of humanistic themes in modern art, underscoring its enduring relevance in times when social bonds remain both vital and fragile.

Conservation and Display Considerations

As a mixed‑media work on paper, Hug requires careful conservation. The paper ground, potentially fragile, benefits from acid‑free mounting and UV‑filtered glazing to prevent yellowing and pigment fading. Controlled humidity and temperature ensure that the charcoal shading and pigment washes remain stable without flaking or bleeding. When displayed, even lighting enhances the contrast between the warm peach and deep charcoal tones, while protective measures guard against direct sunlight and excessive handling. Periodic condition assessments allow conservators to monitor any changes and intervene proactively, ensuring that Galanda’s emotive vision remains intact for future audiences.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Hug (1930) stands as a masterful exploration of human intimacy, rendered through the seamless union of figural abstraction, graphic precision, and emotive color. Against the backdrop of a young Czechoslovakia seeking unity, Galanda distilled the universal act of embrace into an enduring emblem of protection, trust, and solidarity. His innovative melding of folk-inspired symbolism and avant‑garde form created a work that speaks across cultural and temporal divides, reminding viewers that the simplest gestures can carry the deepest meanings. As both a highlight of Galanda’s oeuvre and a milestone in Slovak modernism, Hug continues to resonate, its silent embrace inviting each generation into a shared experience of empathy and human connection.