Image source: artvee.com

Introduction: Aubrey Beardsley and the Spell of Arthurian Legend

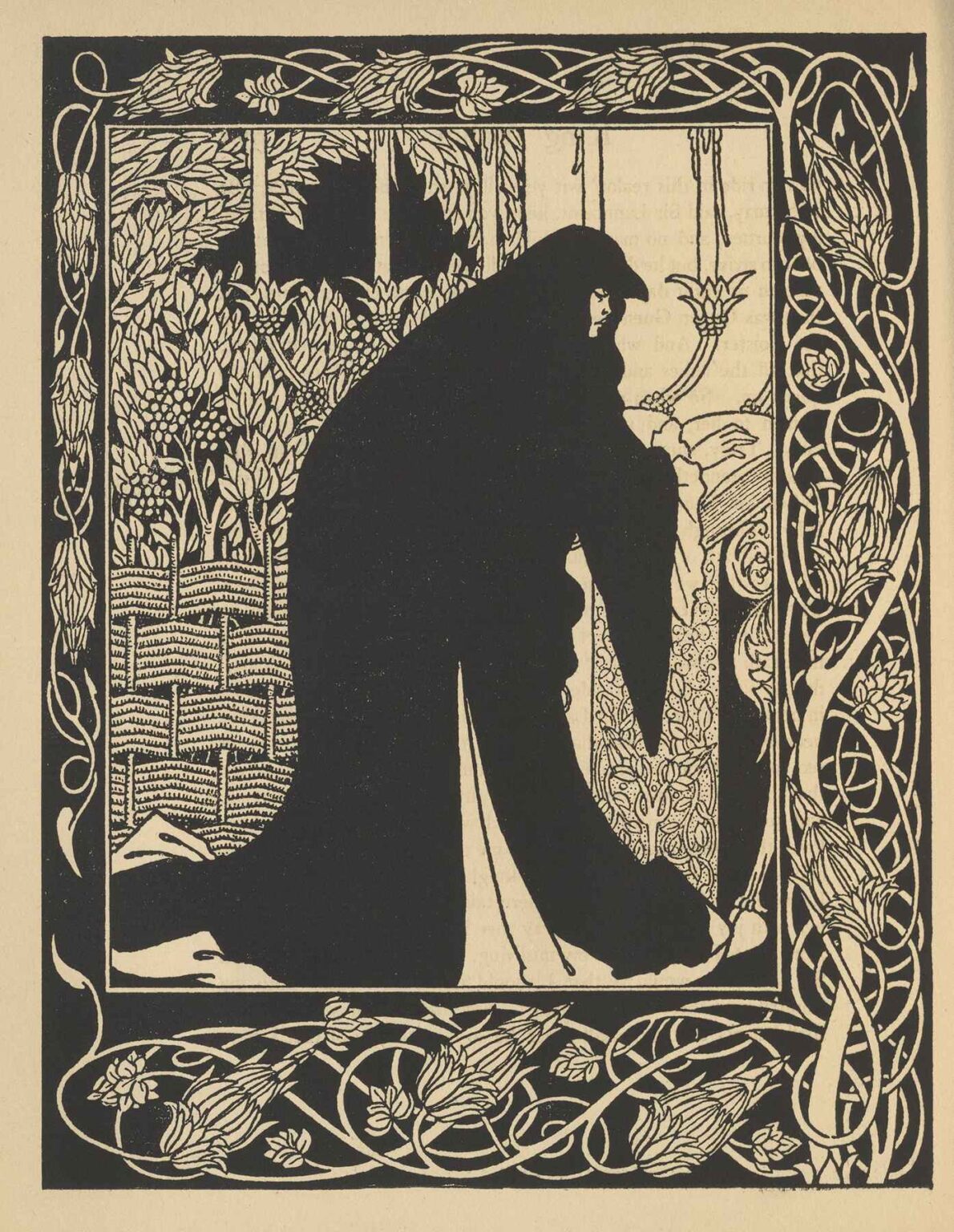

Aubrey Vincent Beardsley remains one of the most striking figures in fin-de-siècle art, renowned for his sinuous black-and-white illustrations that fused decadent whimsy with an unsettling modern edge. Among his most celebrated commissions was the 1893–94 edition of Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur, published by J. M. Dent in twelve parts and later gathered into book form. For this project, Beardsley created well over one hundred drawings that reinterpreted Arthurian romance through the lens of Symbolism, Japonisme, and Aesthetic Movement design. One of the most evocative plates from the series is “How Queen Guenever made her a nun.” In this arresting image the artist translates chivalric narrative into an almost abstract ballet of silhouettes, decorative foliage, and psychological tension. Though executed in simple black ink on pale cream paper, the print teems with complexity—stylistic, emotional, and cultural. Examining this illustration reveals Beardsley’s unique ability to synthesize medieval subject matter with avant-garde visual language, while exploring themes of eroticism, spiritual renunciation, and the performative nature of virtue.

Historical Context: A Young Visionary at Work

In 1893 the publisher Joseph Dent hired the nineteen-year-old Beardsley—still largely unknown—to illustrate Malory’s Arthurian cycle. The commission coincided with a broader Victorian fascination for medieval revival, yet Beardsley had no interest in Pre-Raphaelite sentimentality. Instead, he approached the text with irreverent wit and an eye for stark stylization drawn from Japanese woodcuts, French poster art, and the swirling ornament of Celtic manuscripts. The resulting illustrations shocked and entranced the public: critics complained of their “unwholesome” undertones, while avant-garde circles hailed Beardsley as the enfant terrible of British illustration.

The plate in question appears in Book XVIII, where Queen Guenever, accused of adultery and threatened with burning at the stake, retreats to the convent at Almesbury. There she persuades her loyal attendant—Helena, sometimes called “Dame” in Malory’s text—to take the veil with her. Beardsley seizes upon this moment of renunciation, transforming it into a study of cloaked silhouettes and intertwining vines, far removed from narrative literalism yet steeped in symbolic potency.

Composition: The Dominance of the Silhouette

At the illustration’s center looms a single monumental form: a kneeling, heavily draped figure rendered as an unbroken black silhouette. This somber mass, likely representing Queen Guenever, conceals almost all anatomical detail save for a delicate profile—eye, nose, lips—caught in a sliver of light. The head inclines toward a second, subtler silhouette whose arm rests limply on a bed or bier, implying illness, sleep, or surrender. By reducing figures to near-abstract shadows, Beardsley heightens emotional intensity: gesture becomes everything, and the emptiness surrounding each contour resonates like silence in a darkened chamber.

The entire scene is framed by a thick border of interlaced floral stems and stylized blossoms, laced with Celtic knots and sinuous tendrils. This border is not merely ornamental; it functions as counterpoint to the black interior masses, echoing the tension between worldly opulence and spiritual withdrawal. Outside the border, a wide cream margin isolates the image on the page, giving it the aura of a medieval illumination afloat on modern paper.

Line and Negative Space: A Dialogue in Black and White

Beardsley’s handling of line is both ruthless and refined. The cloak’s edge ripples in an elegant curve that cascades to the ground, while the face of Guenever emerges from negative space—white paper untouched by ink. This play of figure and void creates a dramatic chiaroscuro reminiscent of Japanese kiri-e cut-paper silhouettes. Instead of modeling volume through hatching or tonal wash, Beardsley relies on the viewer’s imagination to fill the abyss of ink with folds of velvet, whispered vows, and religious solemnity.

Within the border, line becomes decorative melody. Lotus-like blossoms and looping stems intertwine with near mathematical precision, their pale interiors contrasting with the dense black of Guenever’s habit. The push-and-pull between heavy fill and delicate line fosters a rhythmic energy that leads the eye around the frame before plunging back to the central silhouette.

Symbolic Flora and Medieval Motifs

Floral forms carry layered meaning throughout Beardsley’s work. In this plate, the dominant blossoms appear to be stylized lilies or bellflowers, symbols of purity often associated with the Virgin Mary. Their proliferation underscores Guenever’s transition from adulterous queen to penitent nun, suggesting the possibility of spiritual renewal even amid scandal. The border’s interlace recalls Celtic manuscript tradition, nodding to Malory’s late-medieval source while simultaneously aligning with Art Nouveau’s mania for serpentine ornament. Vines twist into knots that sometimes resemble sinuous serpents, hinting at temptation never fully conquered.

The interior background reveals a tapestry of tree trunks and densely packed leaves, simplified into flat pattern. This arboreal backdrop evokes both the Garden of Eden and the Greenwood of Arthurian romance—spaces of temptation and refuge respectively. By compressing such connotations into a flattened decorative field, Beardsley collapses narrative time, presenting past sin and present repentance within one unified pictorial plane.

Psychological Reading: Theatrics of Repentance

Although Malory depicts mutual devotion between Guenever and her maid, Beardsley introduces theatrical ambiguity. The queen’s silhouette dwarfs her companion, suggesting a hierarchical imbalance that echoes the power dynamics of court life. Her bowed posture, however, conveys humility—an abnegation of regal authority in favor of monastic obedience. Yet the sheer bulk of her cloak, enveloping and almost predatory, intimates the lingering weight of worldly attachment.

Guenever’s profile, carved from negative space, gazes downward, eyes half-closed. The expression is unreadable: serenity or sorrow, acceptance or lingering guilt. Beardsley’s refusal to clarify invites viewers to project their own emotions into the black void, making the queen’s conversion both personal and universal. The companion’s partial exposure—an arm and faint outline of a face—suggests vulnerability, perhaps foreshadowing the loss of identity that accompanies monastic anonymity.

Technique and Print Culture

Created as a line block print after Beardsley’s pen-and-ink original, the plate exemplifies the period’s fascination with high-contrast reproductive techniques. Publishers of illustrated gift books prized such prints for their crisp reproduction and dramatic impact under gaslight reading conditions. Beardsley exploited this medium by maximizing areas of pure black, which reproduced reliably, while orchestrating fine lines that tested the limits of relief printing.

A close examination of the print reveals slight stippling in the black cloak—tiny pinholes where ink did not fully saturate—adding tactile nuance to the otherwise monolithic silhouette. Similarly, the creamy paper’s natural texture animates negative spaces, preventing flatness and reminding viewers of the hand-crafted origin of mass-produced pages.

Japonisme and Decorative Syncretism

Beardsley’s admiration for Japanese woodblock prints, specifically the kakemono-e vertical scroll format and ukiyo-e silhouette play, is evident. The border’s looping vines echo the symmetrical stylization of karakusa (scrolling foliage) patterns. Meanwhile, the stark silhouette motif resonates with nishiki-e scenes where a single bold outline communicates emotional heft.

Yet Beardsley does not mimic Japan directly; instead, he fuses oriental and occidental influences into a hybrid idiom. Medieval European tapestry aesthetics mingle with flat Japanese space, while the subject matter remains rooted in English literary tradition. This syncretism epitomizes fin-de-siècle cosmopolitanism, wherein artists culled motifs globally to challenge Victorian realism and morality.

Gender and Moral Ambiguity

Victorian and Edwardian audiences were acutely attuned to sexual undertones in art, and Beardsley reveled in toying with these sensitivities. While Guenever’s conversion to nunhood might seem a straightforward moral climax, Beardsley complicates the narrative through visual choices. The enveloping cloak resembles both penitential habit and vampiric wing, allowing for dual readings of sanctity and seduction. The border’s lush vegetation could symbolize Edenic purity or entangling sin.

Such ambiguity mirrors fin-de-siècle anxieties surrounding female agency, sexual transgression, and institutional control. Guenever asserts power by orchestrating her own retreat from court; simultaneously, she submits to ecclesiastical authority. Beardsley’s illustration neither condemns nor absolves; it dramatizes the tension between desire and restraint, aligning with the Decadent fascination with moral gray zones.

Influence on the Arts and Crafts and Art Nouveau Movements

Beardsley’s Malory illustrations arrived amid the flourishing Arts and Crafts movement, which championed hand-crafted quality and medievalism. His bold black-and-white designs offered a modern update to William Morris’s dense patterning. At the same time, European poster designers—Toulouse-Lautrec, Mucha—began incorporating Beardsley’s silhouette trickery into lithographic advertisements. The interplay of heavy outline, vacant space, and decorative borders in “How Queen Guenever made her a nun” thus fed both fine art and commercial design, accelerating Art Nouveau’s spread across Europe.

Reception and Legacy

When the Malory series debuted, conservative quarters deemed some plates indecent, complaining of their “sinister eroticism.” Yet younger critics praised their originality and technical mastery. Over time, Beardsley’s reputation oscillated between scandal and reverence, but today he is recognized as a pivotal bridge from Victorian illustration to modern graphic art. This particular plate—less overtly erotic than some others—showcases his ability to distill narrative into an elegant, haunting symbol that transcends era and language.

Conclusion: A Timeless Ritual in Ink

“How Queen Guenever made her a nun” distills multiple tensions—spiritual and sensual, medieval and modern, abstract and narrative—into a single mesmerizing frame. Through audacious silhouette, ornamental framing, and poetic minimalism, Aubrey Beardsley reimagines Arthurian repentance as a contemplative nocturne of black and cream. The illustration invites viewers to linger within its tangled vines and fathomless darkness, where the act of renunciation becomes both personal confession and aesthetic spectacle. More than a century later, the print endures as a masterclass in the power of line and negative space, proof that the starkest contrasts can conjure the deepest mysteries.