Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

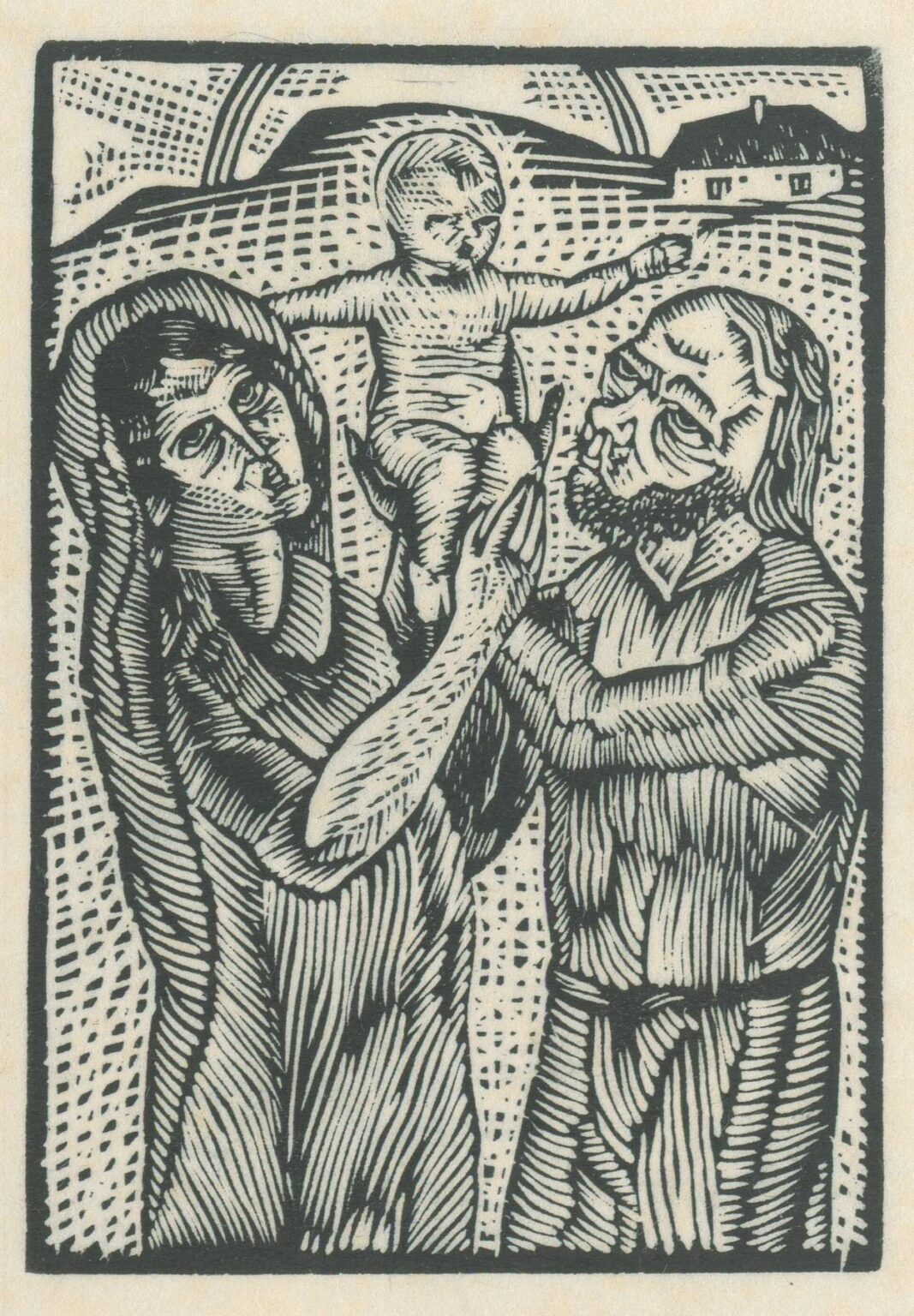

In Holy Family (1924), Mikuláš Galanda masterfully employs the stark contrasts of woodcut to explore themes of devotion, unity, and human tenderness. The print depicts the Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph gently lifting the Christ Child between them, their figures rendered in rhythmic lines that emphasize both individual presence and familial harmony. Against a simplified rural backdrop, the composition transcends mere religious illustration to become a modern meditation on spiritual kinship. By examining the work’s formal qualities, iconographic resonances, and historical milieu, we can appreciate how Galanda transforms traditional subject matter into a dynamic interplay of light, texture, and symbolic depth, marking a pivotal moment in the development of Slovak graphic art.

Historical Context

The early 1920s in Czechoslovakia were a time of cultural renewal following the upheavals of World War I and the birth of the new republic. Artists sought to define a national identity while engaging with broader European avant‑garde movements. Galanda, returning from studies in Budapest and Munich, embraced printmaking as a means to reach wider audiences with accessible yet sophisticated imagery. Religious subjects, long ingrained in Central European visual culture, gained fresh relevance when filtered through modernist sensibilities. Holy Family reflects this environment: it honors a venerable iconographic tradition but does so with a pared‑down aesthetic that resonates with contemporary explorations of form and abstraction.

Mikuláš Galanda and the Printmaking Tradition

Trained initially in academic drawing, Galanda’s journey into graphic media began in the early 1920s when he discovered the expressive potential of woodcut. The medium’s reliance on bold planes of black and white suited his interest in clarity and emotional directness. Galanda’s prints often combined folk motifs with modernist experiment, bridging popular and elite spheres. In Holy Family, he channels the immediacy of traditional devotional woodcuts while asserting a confident personal style characterized by fluid linework and carefully calibrated textures. His approach contributed to a renaissance of printmaking in Slovakia, inspiring contemporaries to explore the power of relief techniques for both narrative and abstract compositions.

Technical Mastery and Woodcut Technique

Woodcut printing demands precision: every line must be carved in reverse on the block, with the white of the paper left intact and the inked areas pressed into sharp relief. Galanda’s Holy Family exhibits mastery of this demanding craft. The varied incision depths create a rich tapestry of line weights—from the deep, velvety blacks that define the figures’ silhouettes to the delicate cross‑hatching that suggests the glow of divinity around the Christ Child. The careful modulation of negative space allows the background hills and distant house to recede, directing visual focus to the tender central tableau. Galanda’s adept handling of the gouge and baren yields a print of remarkable tonal nuance and crispness.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

The composition of Holy Family centers on a triangular arrangement: Mary and Joseph form the base, their arms converging as they lift the Christ Child to the apex. This stable geometry evokes both the Holy Trinity and classical compositional principles of balance and harmony. The figures dominate the foreground, pressing forward into the viewer’s space, while a simple landscape—rolling hills punctuated by a solitary cottage—provides contextual depth without distraction. The horizon line sits high, compressing the background and intensifying the intimacy of the scene. Galanda’s strategic use of scale and positioning ensures that the emotional core remains unequivocally the familial bond.

Line, Texture, and Light

Line functions as the primary expressive tool in Holy Family. Galanda employs strong, rhythmic contours to define drapery folds and facial features, while shorter, parallel strokes render texture and shading. The woodcut medium inherently produces a tactile surface quality: raised ink areas offer a subtle sheen that contrasts with uninked paper. Light is suggested through the interplay of dense hatching and open fields, imbuing the scene with spiritual luminosity. The Christ Child’s halo emerges not as a solid disc but as a halo of fine lines, symbolizing divine radiance integrated seamlessly into the overall pattern. This dynamic interaction of light and shadow underscores the print’s visual and symbolic vibrancy.

Symbolic Dimensions of the Holy Family

The Holy Family has long served as an emblem of piety, domestic virtue, and divine incarnation. Galanda’s interpretation respects these traditions while introducing modernist abstraction. The infant’s outstretched arms evoke both blessing and childlike openness, suggesting a universal invitation to grace. Mary’s serene gaze and Joseph’s protective posture convey complementary aspects of nurturing strength. The rural backdrop alludes to Bethlehem’s pastoral environs but also resonates with the Slovak countryside, rooting sacred history in familiar terrain. Through a synthesis of traditional symbolism and localized references, Galanda renders the Holy Family not just as remote icons but as living figures embodying human aspiration and community values.

Emotional Expression and Gestural Interaction

Despite the woodcut’s formal constraints, Holy Family communicates a profound emotional presence. The slight tilt of Mary’s head toward her child, his poised yet relaxed posture, and Joseph’s gentle support coalesce into a harmonious choreography of care. Facial features, though simplified, reveal subtle expressions: Mary’s contemplative eyes, Joseph’s attentive gaze, and the child’s forward look. These minimal yet evocative gestures invite empathy, drawing the viewer into a shared moment of tenderness. Galanda’s ability to capture such nuanced affect within the rigid lines of relief printing attests to his skill in translating human feeling into visual language.

Relationship to Folk Traditions and Religious Imagery

Galanda’s Holy Family aligns with Central European folk art traditions, where devotional images often circulated in vernacular prints and church decorations. The uncomplicated setting and stylized forms echo rural devotional panels, while the rhythmic linework recalls folk embroidery patterns and wood‑block church carvings. By referencing these popular sources, Galanda situates his modernist reinterpretation within a living cultural tapestry. His print thus bridges the sacred and the everyday, suggesting that spiritual narratives belong as much to humble communities as to grand cathedrals. This fusion of folk resonance and avant‑garde technique exemplifies the artist’s commitment to an art both rooted and innovative.

Modernism and Spirituality

During the interwar period, many artists grappled with reconciling avant‑garde abstraction and spiritual meaning. Galanda’s Holy Family offers a compelling resolution: he eschews ornamental excess while preserving the narrative and symbolic potency of religious imagery. The woodcut’s reductive aesthetics align with modernist ideals of essential form, yet the subject matter affirms the enduring human need for transcendence. In merging these impulses, Galanda contributes to a strand of spiritual modernism that finds new modes for expressing time‑honored beliefs. His print stands alongside works by contemporaries who sought to reimagine iconography for a rapidly changing world.

Reception and Impact

Upon its publication, Holy Family garnered attention for its technical audacity and emotive clarity. Critics praised Galanda’s capacity to marry folk authenticity with modern expressiveness, while collectors valued the print’s devotional appeal. The work circulated not only among art connoisseurs but also in church circles and popular print portfolios, enhancing Galanda’s reputation as both fine artist and graphic innovator. In subsequent decades, Holy Family figured prominently in retrospectives of Slovak interwar art, recognized as a landmark in the revival of woodcut and a touchstone for artists exploring the junction of tradition and modernity.

The Holy Family in Galanda’s Oeuvre

Within Galanda’s broader body of work, Holy Family occupies a pivotal position. It exemplifies his early engagement with woodcut before his later experiments with wood engraving and lithography. The print’s compositional rigor and emotive resonance prefigure themes he would revisit in secular contexts—motherhood, communal bonds, and the sacredness of daily life. As Galanda’s style evolved toward subtler abstraction, the fundamental concerns evident in Holy Family—clarity of line, spiritual depth, and cultural rootedness—remained guiding principles. The work thus serves as both a consummate statement of his early graphic mastery and a foundation for his subsequent innovations.

Enduring Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Nearly a century after its creation, Galanda’s Holy Family continues to speak to artists and audiences alike. Its interplay of modernist design and timeless symbolism resonates in exhibitions on sacred art, printmaking, and Central European modernism. Contemporary printmakers cite the work as an exemplar of how relief techniques can convey profound emotion and narrative complexity. The print’s balance of folk-based imagery and avant‑garde refinement offers a model for cultural dialogues in today’s diverse artistic landscapes. In an era marked by rapid change and spiritual searching, Holy Family endures as a testament to the power of simple yet resonant forms to convey universal human experiences.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Holy Family stands as a masterwork of woodcut artistry—a harmonious union of tradition and innovation, devotion and design. Through precise linework, compositional elegance, and symbolic depth, the print transforms an age‑old religious subject into a living, breathing tableau of familial love and spiritual hope. By situating the Holy Family within a familiar rural context, Galanda affirms the relevance of sacred narratives to everyday life and national identity. More than a devotional image, Holy Family exemplifies the potential of graphic art to engage hearts and minds, leaving an indelible mark on the history of Slovak modernism and the broader story of twentieth‑century printmaking.