Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

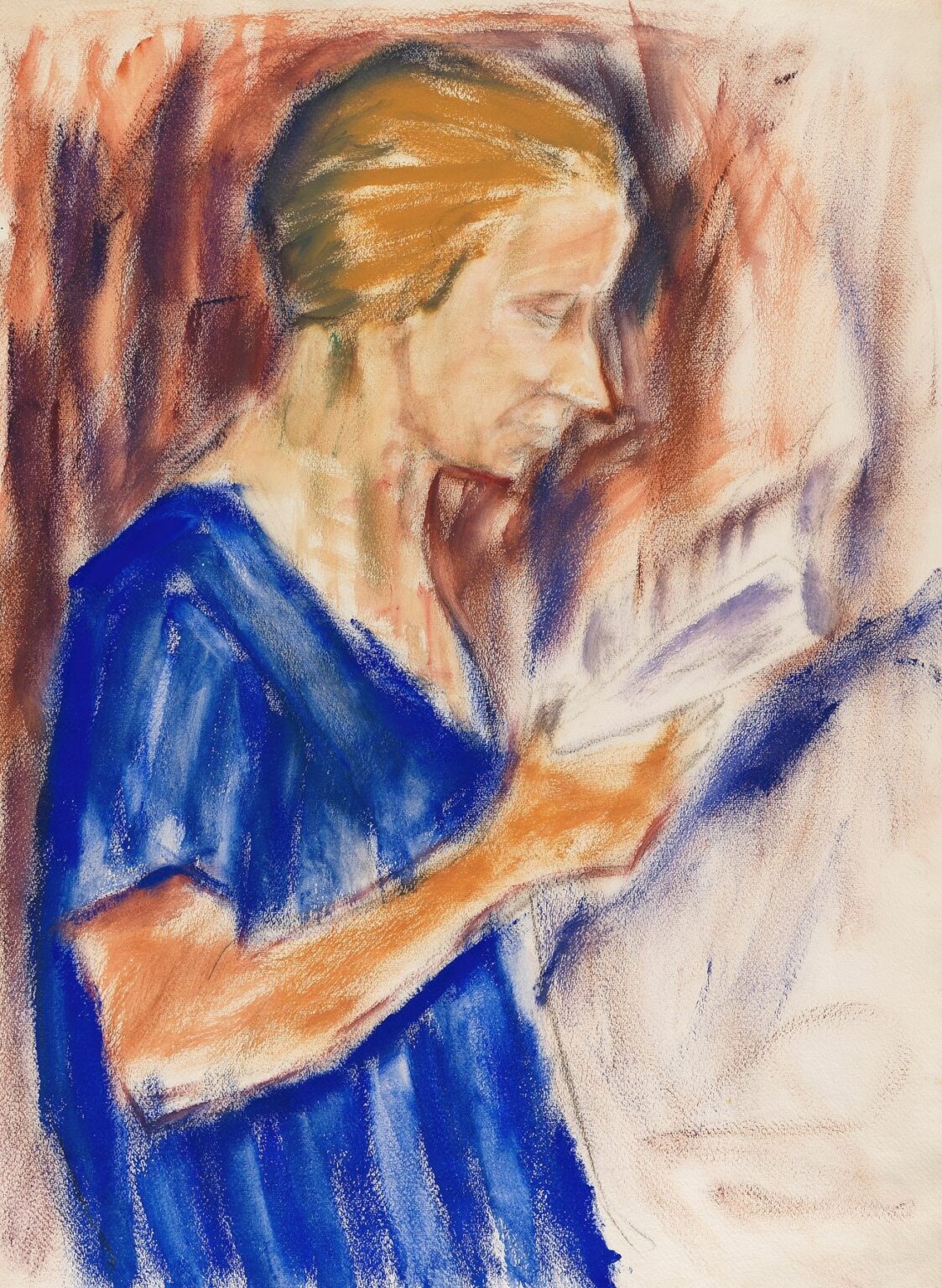

Christian Rohlfs’s “Helene Rohlfs” (1926) stands as a heartfelt testament to both personal affection and artistic audacity. Executed in pastel and gouache on paper, the portrait captures his wife Helene absorbed in reading, her profile rendered with minimal lines yet suffused with emotional depth. Unlike the more formal commissions of his contemporaries, Rohlfs’s portrayal is intimate—Helene’s contemplative pose, the bold washes of blue and red, and the tactile interplay of pastel strokes combine to create a work that is at once deeply human and boldly modern. In this extended analysis, we will explore the historical and personal context of the painting’s creation, trace Rohlfs’s development as an Expressionist portraitist, and examine in detail the formal, chromatic, and psychological dimensions that make “Helene Rohlfs” a pinnacle of his late career.

Historical and Personal Context

By 1926, Germany had endured both the upheaval of World War I and the tenuous peace of the early Weimar Republic. Hyperinflation had subsided, and cultural life experienced a cautious revival. In this period of recovery, Christian Rohlfs (1849–1938) enjoyed renewed recognition as a pioneer of German Expressionism. His mature style—characterized by vibrant color, dynamic line, and a rejection of purely naturalistic detail—placed him among the generation that bridged nineteenth-century academic painting and the avant-garde of the twentieth. It was also a time of domestic stability: Rohlfs lived with his wife Helene in Singen, where she managed the household and often served as his model. The portrait “Helene Rohlfs” emerges from this confluence of public acclaim and private harmony. Far from a detached artist’s study, it is a labor of love, capturing Helene not as an icon but as a real person, immersed in a simple act of reading, bathed in the expressive colors of Rohlfs’s palette.

Rohlfs’s Evolution as an Expressionist Portraitist

Rohlfs’s journey from Naturalism toward Expressionism unfolded over several decades. In his early career, he produced sensitive landscapes and genre scenes grounded in careful observation. A transformative sojourn in Paris around 1903 introduced him to the Fauves’ bold use of color and the raw immediacy of printmaking. Back in Germany, Rohlfs embraced nonrepresentational color and dynamic brushwork, first in landscape oils and then in woodcuts. By the mid-1920s, he applied these lessons to portraiture. Works like “Helene Rohlfs” reveal a confident synthesis: the figure is still recognizable and individualized, yet the handling of pastel, the abbreviated lines, and the abstracted background announce a painterly freedom. Rohlfs’s portraits from this era eschew photographic exactitude in favor of conveying inner life and the tactile pleasure of material.

Composition and Pose

At the heart of “Helene Rohlfs” lies a deceptively simple compositional scheme. Helene is shown in profile, seated and turned slightly toward the right edge of the paper. Her hands—only half-visible—rest delicately on the open pages of a book. This quiet activity offers a window into her character: thoughtful, studious, serene. Rohlfs places her figure against a roughly sketched backdrop of reds and oranges that swirl around her head and shoulders like an abstracted halo. To the left, vertical strokes of blue and gray suggest either drapery or shadow, balancing the warm tones and framing her blonde hair. The diagonal axis from the lower left (her elbow and book) to the upper right (her head) creates a dynamic tension, lending a sense of movement even within the still pose. Negative space—unpainted patches of paper—allows light to enter the scene and prevents the composition from feeling claustrophobic.

Color Palette and Light

One of the most striking features of “Helene Rohlfs” is its bold, restricted palette. The artist uses only a few key hues—cobalt blue for Helene’s dress, warm ochres and reds for the background and hair, and subtle grays and whites for modeling flesh and paper. This economy of color generates a vibrant harmony. The cobalt blue, applied in broad, textured strokes, anchors the lower left quadrant, drawing the eye to Helene’s body and the book. Against this cool mass, the reddish background pulses with warmth, evoking a sense of domestic intimacy or the glow of afternoon light. The transition from blue to red is not gradual but abrupt, underscoring the painting’s Expressionist roots. Helene’s face and hands, bathed in soft ochre and white, glow against both the warm and cool passages, suggesting a self-contained light that emanates from her inner life. Highlights are applied in nearly pure white pastel, catching the ridges of paper texture and guiding the viewer’s gaze to her eyes and the page she reads.

Line and Pastel Technique

Rohlfs’s handling of pastel in “Helene Rohlfs” demonstrates a mastery of both soft and hard edges. The contour of Helene’s profile—from forehead to chin—is drawn with a single, confident line that varies in thickness, echoing the calligraphic freedom of his woodcut outlines. Within this boundary, the pastel is applied in layers: soft, broad strokes of pigment establish mass and color, while lighter, scribbled touches build texture and nuance. In areas such as the hair and the red background, Rohlfs uses a mix of dry brush-like drags and wetly blended passages to create a sense of depth. The dress’s folds are articulated with swift upward strokes, their ridged textures catching the light. Elsewhere—around the book and hands—he uses finer, more controlled strokes to convey the delicate interplay of light on paper and skin. Throughout, the paper’s tooth shows through, contributing to the painting’s tactile immediacy.

Depiction of Helene and Psychological Insight

Far from a fashionably dressed sitter or an object of idealized beauty, Helene in this portrait appears absorbed, even slightly melancholic. Her closed eyelids and the gentle downturn of her mouth suggest concentration or introspection rather than posed allure. Rohlfs captures subtle wrinkles at the eye’s corner and the gentle slope of the nose with just a few pastel lines, conveying age and lived experience. The hands, though sketched with economy, retain a sense of fragility—the delicate gestures of a reader turning pages. Through these details, Rohlfs offers an unvarnished glimpse of his spouse: her quiet intelligence, her domestic grace, and perhaps her endurance in years of a shared creative life. The painting’s psychological resonance derives less from dramatic expression and more from the sensitive observation of Helene’s habitual calmness and composure.

Relation to Broader Expressionist Trends

Within the wider Expressionist movement, “Helene Rohlfs” exemplifies the turn toward intimate, small-scale works that foreground personal experience over grand social statements. While many Expressionists used dissonant color and distortion to critique urban alienation or political violence, Rohlfs focused on the sanctity of everyday life—domestic scenes, family members, close landscapes. His combination of vibrant pastel techniques and simplified form aligns him with artists like Paula Modersohn-Becker and Emil Nolde in exploring humanity’s inner core. Yet Rohlfs’s style remains singular: his disciplined contour, his judicious palette, and his seamless blend of figuration and abstraction mark him as a quietly radical figure, one who extended Expressionism’s reach into portraiture with subtlety and emotional nuance.

Technical and Conservation Considerations

As a pastel and gouache work on paper, “Helene Rohlfs” requires careful conservation to preserve its vibrant hues and delicate surface. The drawing should be stored and displayed behind UV-filtering glazing, with stable humidity and temperature to prevent pigment flaking and paper warping. Museums that hold the piece often use acid-free mats and archival hinges to secure the sheet without damaging it. When well conserved, the pastel’s chalky textures and the gouache’s milky opacities retain their original impact, allowing viewers to sense the immediacy of Rohlfs’s hand and the intimate bond between artist and sitter.

Legacy and Influence

Over the decades, “Helene Rohlfs” has been recognized not only as a beautiful portrait but as a landmark in the tradition of modernist portraiture. Art historians cite it as evidence of Expressionism’s capacity to convey empathy and psychological depth through pared-down means. Contemporary pastel artists often point to Rohlfs’s handling of color and line as a model for balancing spontaneity with compositional rigor. For Rohlfs himself, the work stands as one of his finest late-career achievements, demonstrating that even in his seventies he continued to innovate and to find new expressive possibilities. Exhibitions of German Expressionism frequently include “Helene Rohlfs” to illustrate the movement’s intimate dimension and its embrace of color’s emotional resonance.

Conclusion

Christian Rohlfs’s “Helene Rohlfs” (1926) remains a masterful conflation of personal affection and avant-garde artistry. Through confident outlines, vibrant pastel washes, and sensitive psychological observation, Rohlfs transforms a domestic moment—his wife reading—into an enduring symbol of Expressionist innovation. The portrait’s bold contrasts of warm and cool, its dynamic composition, and its nuanced depiction of Helene’s introspective calm testify to Rohlfs’s lifelong commitment to conveying emotional truth through paint. As both a document of a creative partnership and a milestone of twentieth-century portraiture, “Helene Rohlfs” continues to captivate, inviting each new generation to discover its layers of color, line, and humanity.