Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

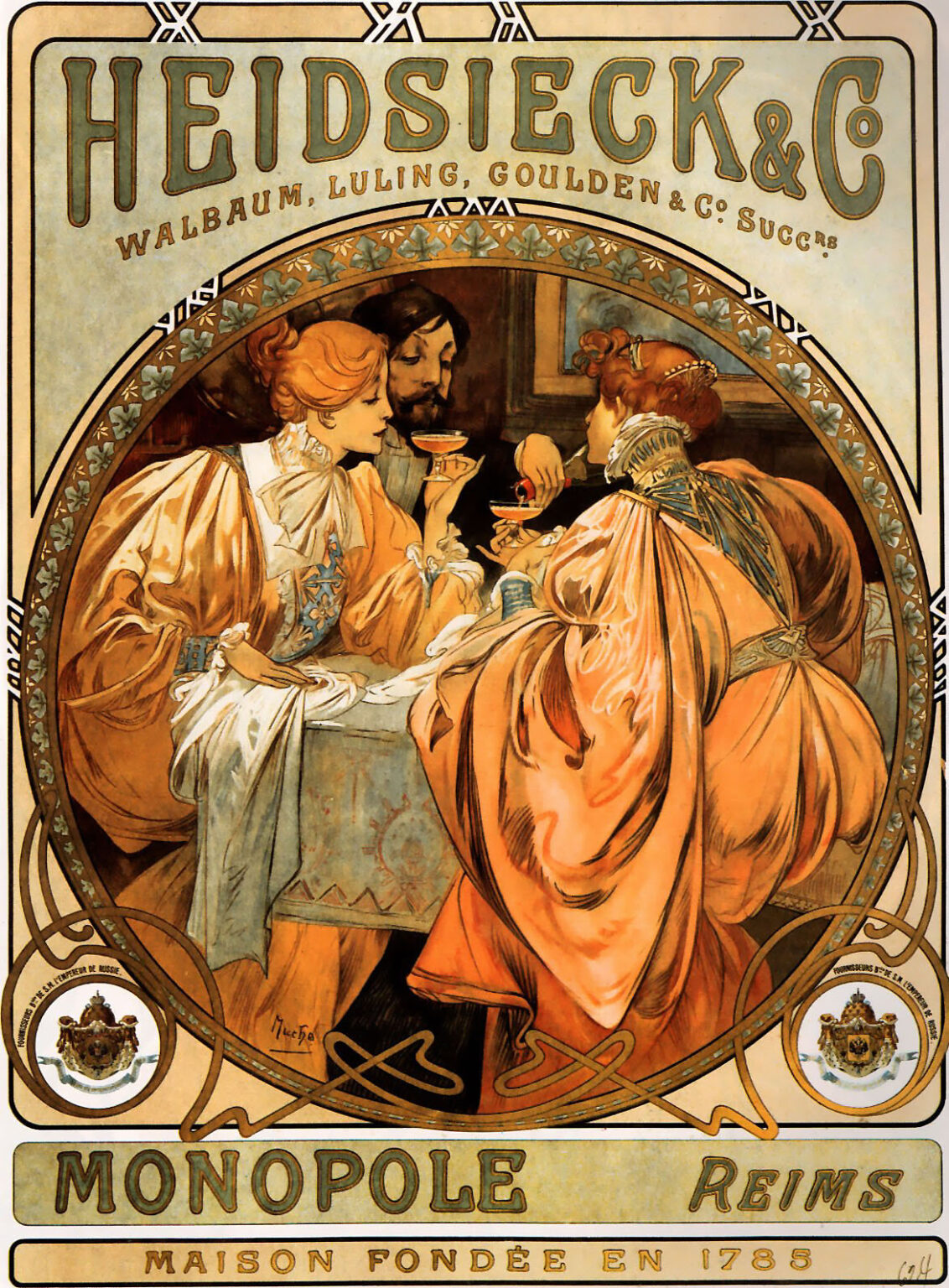

Alphonse Mucha’s 1901 advertisement “Heidsieck” distills the glamour and optimism of the Belle Époque into a single frame. Designed for the Champagne house Heidsieck & Co Monopole, the lithograph shows an intimate scene of urbane celebration enclosed within a halo-like roundel and wrapped in a lattice of Art Nouveau ornament. Mucha turns a commercial poster into an aspirational tableau: not just a drink to be bought, but a lifestyle to be inhabited. The work belongs to the mature period of Mucha’s Paris career, when his vocabulary of flowing lines, floral borders, and radiant figures was already synonymous with luxury brands. Here that vocabulary is tailored to champagne culture—convivial, opulent, and unmistakably modern in 1901.

Commission, Brand, and Historical Moment

Heidsieck & Co was a storied Champagne house founded in Reims in 1785, an origin proudly lettered at the base of the poster alongside the word “Monopole,” the firm’s flagship cuvée. Mucha’s commission aligns with a broader turn-of-the-century phenomenon: the elevation of product advertising to high design. Urban boulevards had become outdoor galleries for color lithography, and Champagne producers competed visually for attention. Mucha’s name alone carried prestige; by associating with him, Heidsieck presented itself as a leader in taste. The date 1901 is significant. Europe’s great capitals were thriving, the café and salon were at the center of social life, and the public image of champagne had shifted from aristocratic privilege to a more accessible symbol of celebration for the bourgeoisie. The poster captures this transition with a scene that feels exclusive yet inviting.

Composition and the Arc of Sociability

The composition is organized around a large, almost architectural roundel that frames a trio in conversation. Two elegantly dressed women occupy the foreground, their voluminous sleeves and layered gowns forming soft sculptural masses. Between them, slightly set back, a gentleman lifts a coupe of champagne. The circular frame acts like a proscenium, and within it a second rectangle—perhaps a painting or mirror—adds depth to the interior. Mucha positions hands, cuffs, and glass stems as small focal points that punctuate the arc from left to right: offer, acceptance, toast. The curvature of shoulders and the sweep of fabric guide the eye in a continuous loop, reinforcing the idea of sociability as a cycle of exchange. The poster sells a beverage by visualizing a ritual.

The Art of Lettering and Brand Placement

Mucha’s control of lettering is more than decorative; it is strategic. “HEIDSIECK & Co” crowns the design in monumental capitals, each letter given breathing room through a generous top margin and an elegant internal rhythm of thick and thin strokes. Beneath, the successorial line “Walbaum, Luling, Goulden & C° Succrs” is integrated into the arch so it reads as part of the architecture rather than a disruptive caption. At the base, “MONOPOLE” and “REIMS” sit within a rectangular cartouche whose cool gray ground projects the words forward like engraved metal. The date of founding, “Maison fondée en 1785,” anchors the brand in lineage. All the textual elements work hierarchically—name, provenance, product—while the border’s intertwining lines fuse typography with ornament, producing a brand environment rather than isolated labels.

Color, Light, and the Taste of Champagne

The palette is a study in golden effervescence. Apricots, ambers, and honeyed creams dominate the garments and skin tones, echoing the hues of champagne held in shallow coupes. Cooler pale blues appear in the tablecloth and trim, setting off the warm tones with a refined contrast. Mucha avoids strong black except in small accents—the gentleman’s mustache, hair shadows, and a few interior lines—so nothing interrupts the soft glow that seems to emanate from within the circle. Highlights bloom across satin sleeves and ruffled collars like the play of light on glass. Color here is associative. One can almost infer taste and temperature from the chromatic choices: chilled gold against cool gray, a sparkle of white on glass rims, a whisper of rose in cheeks. The color story enacts the sensory promise of the product.

Line, Ornament, and the Signature Arabesque

Mucha’s line is famously lyrical, and in “Heidsieck” it achieves a dual function. Inside the roundel, contour lines are supple and descriptive, caressing folds of fabric and creating volume with remarkable economy. Outside the roundel, lines harden into an ornamental network: interlaced bands that loop, knot, and unfurl across the border. This contrast dramatizes the movement from decorative frame to living scene. The border’s stylized motifs—tiny clover-like repeats around the arch, slender straps that cross and return—echo the effervescence of champagne in visual syntax. The entire poster feels carbonated; the line never sits still. Mucha’s arabesque becomes a metaphor for the rising bubbles and lively conversation within.

Fashion, Gesture, and the Performance of Elegance

The two women are dressed in fashionably exaggerated sleeves and high, ruffled collars, the silhouettes common to the late 1890s and early 1900s. Mucha delights in the tactile effects of satin, taffeta, and lace, using subtle gradient shading to suggest crispness and sheen. The left figure bends slightly forward, chin tilted and eyes half closed, in a gesture that conveys attention and complicity. The right figure, seen largely from behind, anchors the composition with a luminous mass of fabric and a fine belt, her head turned toward the group in a pose that is both intimate and decorous. Their hair is looped and coiled into coiffures embellished with pins, a nod to modern self-styling. Gestures and costume together communicate the brand promise: Heidsieck accompanies occasions where people are at their best.

Space, Furniture, and the Cultivated Interior

Though the poster’s space is shallow, Mucha hints at an interior world. A table swathed in a patterned cloth supports the social exchange; its diagonal thrust leads our eye into the group while also serving as a pedestal for the glasses. Behind the trio, a framed panel reads as artwork or window, implying that this is a cultivated environment where art and conversation mingle. The furnishings are never described in detail; the merest suggestion suffices to conjure a salon. The effect is to make the drink appear at home among tasteful surroundings, positioning Heidsieck as a natural accessory to culture itself.

Symbolic Reading and the Iconography of Celebration

Beyond advertising, the image has a clear iconography. The circular frame resembles a halo or medallion, elevating the mundane act of toasting into ceremony. The three figures can be read as a secular trinity of social virtues: hospitality, conversation, and pleasure. The women’s radiant garments and the gentleman’s poised hand articulate roles in this micro-drama of exchange. Even the coats of arms positioned at the lower corners participate in symbol-making, linking the present moment to heraldic tradition and institutional prestige. The poster’s rhetoric is that of continuity—your modern celebration participates in a lineage that stretches back to the house’s eighteenth-century founding.

Lithographic Craft and the Look of Multiplicity

As a color lithograph, “Heidsieck” draws power from the technical possibilities of layered stones. Mucha was a master of translating painterly modeling into flat color areas that could be mass-produced without losing richness. The poster’s soft gradients suggest careful registration and meticulous inking. The cream ground bordering the poster is not blankness but a deliberate stage for the warm palette to glow. Because lithography allows for large, flat areas, Mucha’s forms read crisply from a distance, crucial for street-side legibility. At the same time, the image rewards proximity with delicate textures and hairline detail. The dual legibility mirrors champagne’s own appeal: immediate refreshment with layers of nuance.

Comparison with Mucha’s Other Commercial Works

“Heidsieck” stands alongside Mucha’s celebrated posters for Sarah Bernhardt and luxury goods, yet it differs in tone. The theater images often dramatize a single star, elevating personality to myth. In product posters such as Job cigarette papers or Moët & Chandon, Mucha sometimes isolates a single woman who incarnates the brand. By contrast, the Heidsieck poster foregrounds a social triad and an interior scene. It trusts the power of sociability rather than the charisma of a lone figure. This compositional choice aligns perfectly with champagne’s use-case and marks the advertisement as unusually narrative within Mucha’s portfolio. It bridges portrait and genre scene without abandoning the iconic clarity that made his posters so effective.

Champagne Culture and the Belle Époque Ideal

In the early twentieth century, champagne was not merely a beverage; it was a code for modern leisure. The coupe glass, with its wide, shallow bowl, signals a fashionable preference of the era. The women’s couture and the gentleman’s neatly groomed features suggest a milieu of café concerts, art exhibitions, and salon evenings where wit and refinement were social currency. Mucha captures the ethics of pleasure that defined Parisian life at the fin de siècle: cultivated yet spontaneous, cosmopolitan but rooted in ritual. By placing Heidsieck within that world, the poster promises buyers an entrée into a broader cultural script of joy and success.

Gender, Gaze, and Negotiated Modernity

Mucha’s women have often been described as decorative muses, but in “Heidsieck” they are also agents of taste. The left figure’s poised hand seems to offer or receive a glass; she mediates the ritual. The right figure’s turned back resists the frontal consumer gaze, inviting us to observe without intruding. The gentleman, slightly recessed, does not dominate the scene; his role is to complete the circuit of conviviality. The gender dynamic is balanced rather than hierarchical, which suited a market increasingly aware of women’s roles as consumers and trendsetters. The poster sells aspiration through mutual regard, not through one-sided display.

The Frame as Architecture and the Logic of Flow

Mucha treats the border as architectural ornament that both contains and animates the interior. Its looping tendrils enter at the corners, cross, and re-emerge, echoing the passage of conversation around a table. The small repeated motifs along the arch behave like tesserae in a mosaic, adding rhythm without crowding the image. This orchestration of frame and subject exemplifies Mucha’s belief in a total decorative environment, where typography, ornament, and figure form a continuous system. The viewer experiences the poster as a single, flowing organism rather than a collage of parts. Such unity was central to Art Nouveau’s ambition to harmonize art and life.

Time, Memory, and the Promise of Continuity

The inscription “Maison fondée en 1785” establishes a timeline that stretches from Enlightenment-era Reims to the modern city. Mucha’s scene, while resolutely contemporary in costume, feels timeless in its circular composition and ritualized gestures. The poster suggests that by choosing Heidsieck, one enters not only a moment of celebration but a tradition. That promise of continuity—pleasure repeated, memory renewed—is reinforced by the circular format, which visually refuses a terminal point. The eye returns again and again to the glasses, the smiles, the shimmering sleeves. The brand becomes a conduit between past festivities and those yet to come.

Material Luxury and Tactile Persuasion

Much of the poster’s persuasiveness lies in its tactile imagination. Satin sleeves are rendered with creamy gradients that imply cool smoothness under the fingers. Ruffled cuffs imply a whisper of sound when lifted. The glass stems look delicate but firm, a balance of fragility and control that parallels the drink’s own interplay of sparkle and structure. Even the border reads like worked metal or carved wood, materials associated with crafted interiors. By stimulating recollections of touch and texture, Mucha transforms the flat poster into a multisensory prompt; the viewer can almost feel the room and therefore desires to step into it.

Urban Display and the Theater of the Street

Posters in 1901 were encountered at scale on kiosks and walls. “Heidsieck” is engineered for such public theaters. From a distance, the dominating name and warm central circle seize attention. As one approaches, details of hairpins, embroidery, and tiny heraldic seals engage the eye. The design thus stages a choreography of viewing: hook, approach, linger. This layered legibility enhanced brand recall and justified the investment in a star designer. Moreover, the poster would have conversed visually with neighboring advertisements, its restrained palette and refined ornament distinguishing it from louder, more saturated competitors. In the marketplace of images, Mucha sold sophistication as a differentiator.

Preservation, Reproduction, and Lasting Appeal

Many early twentieth-century commercial posters have vanished with the weathered kiosks that bore them. “Heidsieck” survives through preserved impressions and countless reproductions in books and collections. Its lasting appeal derives from an equilibrium that is hard to counterfeit: lavish but not gaudy, intimate yet public, ornamental yet clear. It captures the essence of Art Nouveau’s synthesis while remaining specifically tailored to a brand. For viewers today, the poster functions as a time capsule of refined sociability, but it also still works as persuasion. The longing it visualizes—for good company, a beautiful room, and a celebratory glass—has not dimmed.

Why “Heidsieck” Endures within Mucha’s Oeuvre

Among Mucha’s advertising designs, “Heidsieck” is notable for how thoroughly it integrates narrative and ornament. The poster does not simply drape a product name over a beautiful face; it builds a world in which the product naturally belongs. The world is convincing because its elements, from typography to gesture, are mutually coherent. Every curve, color, and capital letter participates in a single promise: that Heidsieck Champagne accompanies the brightest hours of life. The work exemplifies Mucha’s belief that beauty is not an accessory but an organizing principle. By giving form to that belief, the poster clarifies why Mucha’s Art Nouveau remains evergreen. It is not a style grafted onto life; it is a way of ordering experience so that ordinary acts—like raising a glass—reveal their ceremony.