Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

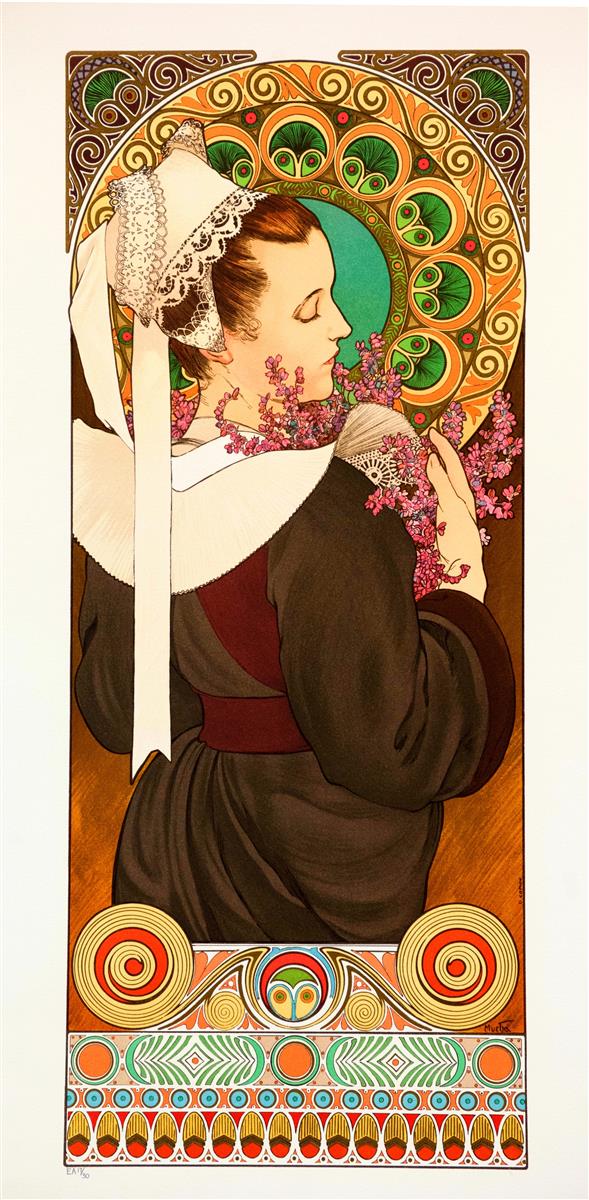

Alphonse Mucha’s “Heather from Coastal Cliffs” condenses an entire seashore climate into a single, luminous panel. A young woman, turned in gentle profile, cradles sprays of pink heather against a dark dress. She is haloed by a richly articulated disc whose nested rings resemble seashells, tidal pools, and peacock eyes, and she stands atop a patterned base that reads like a carved lintel or a woven textile. The work belongs to Mucha’s mature cycle of floral personifications from the early 1900s, in which a specific plant becomes the key to mood, place, and character. Here, the heather brings with it the story of windswept edges—the resilience of blossoms that thrive where salt and weather grind the land to its essence. The panel’s measured grace reveals an artist who could make graphic design breathe like music, binding figure, botany, and ornament into one sustained line.

Historical Moment

Created in 1902, “Heather from Coastal Cliffs” stands inside the fertile middle of Mucha’s Paris years. By then he had revolutionized the poster with his collaborations for the stage and with his radiant allegories, and he was exploring the decorative panel as an object to be collected and lived with. These tall, arched compositions—each devoted to a flower, a gem, or a season—gave him the freedom to refine the grammar of Art Nouveau: the elastic contour, the halo-like frame, the union of image and ornamental architecture. The work distills lessons he drew from printmaking, folk craft, and classical design and translates them into a domestic scale that made modern beauty affordable and intimate.

Subject And Iconography

The subject is as simple as a prayer. The woman turns her face slightly inward, eyes lowered, and inhales the scent of heather. The plant’s wiry stems press gently against a white collar and embroidered lace; individual bells form clouds of violet-pink around her throat and hands. Mucha builds an allegory of attention from this small action. Heather is a coastal survivor—rooted in poor soil, tolerant of wind, persistent where noble garden species cannot endure. In her arms, the plant becomes a standard of steadfastness. Rather than dramatize the ocean directly, Mucha gives us its emissary: a flower that carries the story of rock, spray, and sky within its form.

Composition And Format

The panel’s architecture is deeply satisfying. A tall, rounded niche houses the figure, while a large, layered disc locks behind her head like a solar-lunar device. The figure’s contour traces a soft S-curve from the long white ribbon of the coif at left down through the sleeve and back up through the raised forearm. The bouquet becomes a pivot that turns the body inward; the lowered gaze completes the spiral. Mucha’s compositions always choreograph the viewer’s eye; here, the route is crescent-shaped, circling the disc, settling on the face, following the hands, and returning to the floral cloud. There is no empty space: even the quiet background fields serve as rests in the music, supporting the pictorial rhythm without competing with it.

The Halo As Ornamental Cosmology

The halo is one of Mucha’s signature devices—a secular aureole that dignifies the subject while clarifying composition. In “Heather from Coastal Cliffs,” the disc is built from nested rings filled with rounded cells, each bordered by tidy lines and dotted accents. Some cells carry deep green, others amber or teal, creating a visual tide that pulses around the head. The effect is coastal: think of tide pools, sea urchins, shells, and eddies. At the same time, the halo performs a compositional function, separating the profile from the surrounding ornament so that the viewer reads the face first. The disc thus operates as both cosmic sign and technical solution, uniting symbolism and design in a single stroke.

Costume And Regional Memory

Mucha anchors his allegories in the dignities of folk costume. The woman’s lace coif with its long ribbons, the white collar that spreads like a gull’s wing, and the sober dark dress suggest the wardrobes of Atlantic villages—Brittany and other coastal regions where textiles carry centuries of careful labor. He renders lace with exquisite economy: a few fine strokes and pale stones of white are enough to convince us of knots, air, and weight. The costume does more than charm. It places the flower in human society, implying festivals, households, and the kind of work that coexists with hard weather. The result is a portrait of belonging.

Color As Weather

The palette is a conversation between earth and sea. Deep browns of the dress create a windbreak that allows the floral pinks to glow. The halo’s greens and teals summon water, while its ambers and ochers recall dune grasses and late afternoon sunlight. Mucha distributes warm and cool so that the panel feels ventilated; nothing is heavy, nothing flimsy. The pink of heather not only sweetens the composition; it touches the cheek, neck, and hands, spreading an almost perfumed warmth through the figure. Even the patterned base at the bottom keeps the climate in play with alternating rows of coral, mint, and sea-blue.

The Line That Holds Everything

Mucha’s contour is legible at a glance and inexhaustible under scrutiny. Thickening slightly at turns, thinning through lace and ribbons, it protects color without imprisoning it. The “whiplash” curves beloved by Art Nouveau are present in the coif’s tails, in the elliptical pockets of the halo, and in the scrolling ornaments at the base, but the line is never mannered. It moves with a purpose: to let the eye travel easily, to keep form articulate, and to tie together the disparate textures of skin, textile, and plant. The panel could be stripped of its colors and still work as a drawing because the line sings the structure.

Lithographic Intelligence And Surface

Although the image reads like a painting, it is composed with lithography in mind. Flat fields, delicately modulated washes, and clearly defined edges ensure that the design reproduces with vibrancy. Mucha’s genius was to treat these technical constraints as virtues, creating a style where color lies like enamel and light is built by adjacency rather than glaze. Here, the heather’s bells are suggested with small stipples and short strokes; the lace’s pores are tiny, sparing notes; the background fields are softly brushed, allowing the figure to advance without theatrical shadow. The surface is calm and sure—perfect for a picture meant to live on a wall for years without exhausting the eye.

Heather’s Symbolism And The Ethics Of Resilience

Heather signifies luck, protection, and endurance in northern European lore. It covers poor ground with purple haze, binds soil against erosion, and feeds bees when gardens fade. Mucha draws all of that into his allegory. The woman, almost like a votary, presses the plant to her throat as if claiming its strength as her own. The choice of a coastal variety intensifies the metaphor: here is beauty that survives sea winds and salt. In an urban 1902 interior, such an image would have carried a quiet moral—refinement without fragility, grace that knows how to stand.

Gesture And Psychology

The figure’s lowered eyelids and nearly smiling mouth create an inward, contemplative mood. She does not display the bouquet to us; she receives it. The right hand’s fingers, lightly pinched, check the stems not out of nervousness but as if to hold a thought steady. The left hand secures the spray at the shoulder, pulling the flower into the shelter of the collar. There is an ethics in this choreography. The body becomes a haven for the delicate, a promise that attention and protection are forms of love. The panel’s emotion is therefore not romance but caretaking.

Ornament As Meaningful Ground

Mucha’s lower register is a marvel of condensed architecture. Spirals anchor either side like golden mooring stones. Between them a fan of scrolls and ovals directs the eye toward a central medallion, a tiny owl-like face formed by layered crescents and circles, perhaps a playful nod to watchfulness and wisdom. Below, a band of repeating discs, leaves, and seed-like ovals suggests the fertility of coastal soil when tended with patience. Ornament in Mucha is never empty; it is a chorus that echoes the solo sung by the figure and flower.

Sound, Scent, And Tactility

Although a visual work, the panel evokes other senses. The heather seems to exhale a clean, resinous perfume. Lace whispers as it moves against the collar. The sea-like palette hums with a low, constant sound—wind through grass, tide turning stones. Mucha builds these sensations through small visual cues: the tiny breaks in contour that suggest softness, the way the ribbon drops with a believable weight, the clusters of blossoms that compress where they touch fabric. This multisensory suggestion enlarges the image’s hospitality; we do not only look, we inhabit.

Parallels And Contrasts With Sister Panels

“Heather from Coastal Cliffs” shares kinship with Mucha’s other floral panels from the period, including thistle, iris, and carnation personifications. Compared to thorny thistles or luxuriant irises, heather brings a humbler charisma: no dramatic architecture, just steady color and abundant tiny bells. The costume here is more reserved than in some works, emphasizing the solemnity of coastal life and setting a quiet stage for floral joy. Where other panels pose frontal goddesses, this one turns away slightly, lending privacy to the scene and encouraging the viewer to mirror the subject’s inwardness.

Folk Memory And Cosmopolitan Design

A key to Mucha’s appeal is the way he marries local memory to metropolitan polish. The lace coif and sober dress root the panel in centuries of craft; the halo and graphic base transform those references into a modern decorative system. Instead of reproducing a single village costume, he composes an ideal costume that condenses many traditions into a symbol of human making. The union of these registers—folk and cosmopolitan—allows “Heather from Coastal Cliffs” to speak to viewers far from the sea while preserving the dignity of the people who live there.

Time Of Year And Inner Season

Heather blooms late; it is a flower of thresholds, appearing as summer yields to autumn. Mucha inflects the palette accordingly. Warm ambers at the edges of the halo suggest harvest light, while the dress’s depth forecasts cooler nights. The panel’s mood is therefore a kind of seasonal wisdom: energy turning inward, beauty concentrated, labor gathered into ritual. The woman’s half-closed eyes read like a weather report for the soul—less sparkle, more glow.

Audience And Domestic Life

These panels were made to be companions in homes, salons, and studios. Their verticality suits narrow walls; their calm suits daily living. “Heather from Coastal Cliffs” would have offered a quiet counter-climate to the speed of the city: a tide of greens and pinks to rest in, a reminder that attention is itself an art. The combination of ornamental richness and psychological hush makes the image a generous roommate—it stands near without crowding the room, it remains legible across space yet rewards close inspection with lace, leaves, and stippled bells.

Technique, Edge, And the Discipline of Restraint

Mucha’s restraint is as important as his exuberance. He avoids heavy modeling and dramatic shadows; he trusts adjacency and pattern to carry depth. Edges are calibrated: firm around the face and hands to preserve human presence, softer at the dress’s folds so that mass does not become fuss. Highlights are few and strategic—the moist glint on the lower lip, the cool sheen on a ribbon, the brighter spots within the halo’s oculi. This economy lets viewers breathe. In a style sometimes caricatured as ornate, “Heather from Coastal Cliffs” demonstrates how control makes ornament sing.

Legacy And Continuing Relevance

The panel remains fresh because it proposes a generous vision of modern life. It does not reject industry or the city; it simply invites nature and craft back into the conversation. Designers still borrow its palette for coastal interiors; typographers admire the logic that binds ornament to structure; artists studying narrative see how a single gesture can carry a whole story. Perhaps most importantly, the image models a way of looking at the world where resilience is beautiful. On today’s crowded walls—digital and physical alike—the picture keeps a small patch of coast open in the mind.

Conclusion

“Heather from Coastal Cliffs” gathers wind, water, plant, and person into a single, articulate harmony. The halo turns into a compass of tides; the lace and ribbon honor the hands that make; the heather unites toughness with tenderness; the figure herself becomes a threshold where exterior weather and interior calm meet. Alphonse Mucha had many gifts, but none greater than this: the ability to build a world out of line and color that viewers can live inside. In 1902 as now, the panel offers more than decoration. It offers a practice—holding close what endures and walking forward with grace.