Image source: wikiart.org

First Look: A Portrait That Thinks Out Loud

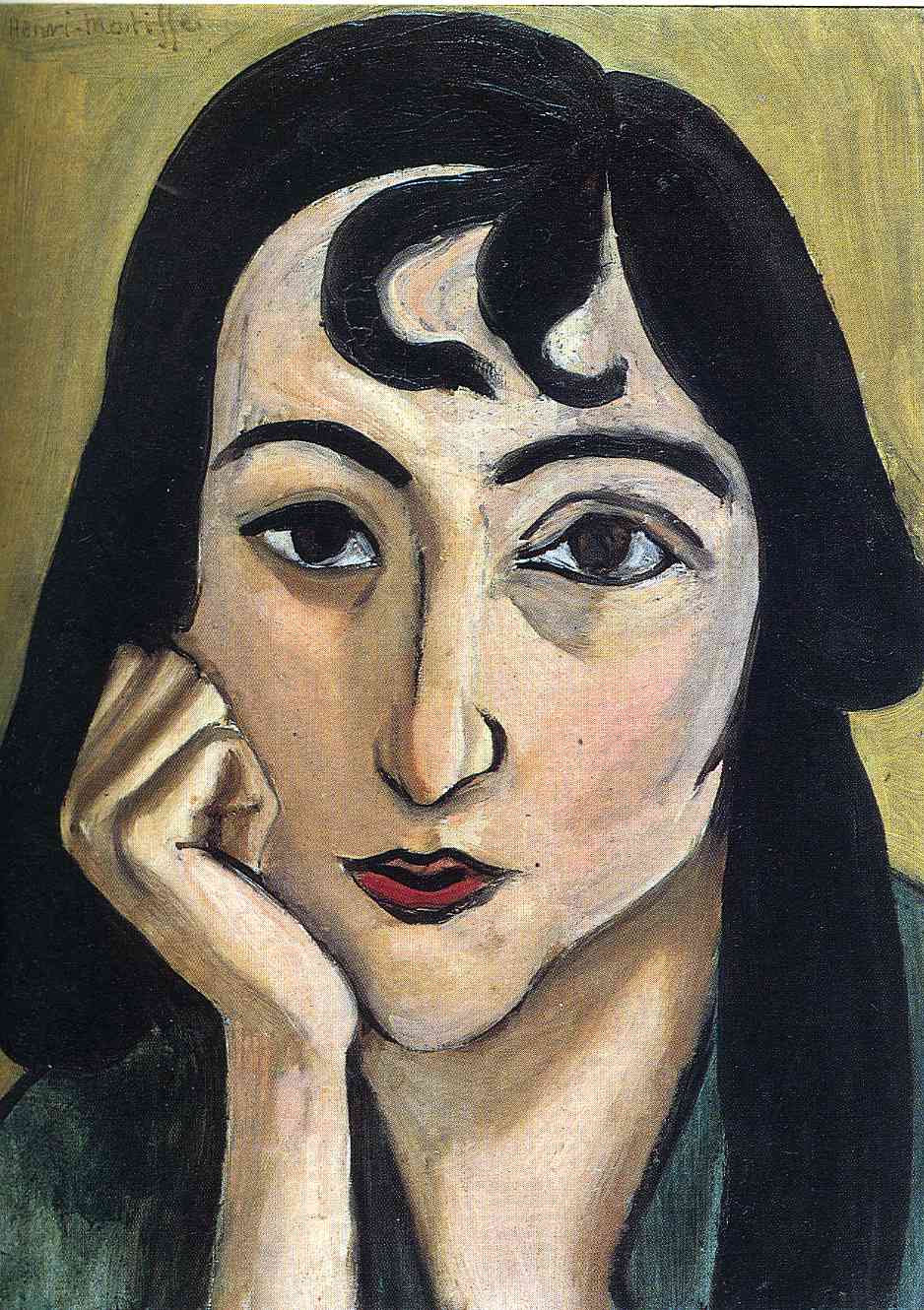

Henri Matisse’s “Head of Lorette with Curls” (1917) meets you at close range, eliminating everything not vital to a direct encounter with a thinking, breathing person. The head fills the frame; a hand props the cheek; the eyes, wide and slightly asymmetrical, study something just beyond us. A dark curtain of hair surrounds the pale oval of the face, and a single arabesque of fringe—those signature curls—spirals across the forehead like a calligraphic signature. Matisse does not settle for likeness. He builds a readable, living structure out of a few controlled relationships: warm flesh against cool dark, elastic black contour against open, brushy planes, sculptural modeling pared down to essential turns. The result is intimate without being sentimental and modern without sacrificing humanity.

Lorette in 1917: Muse, Method, and Measure

Lorette was Matisse’s most persistent model during 1916–1917, a period of intense experiment. The war-years language he forged with her is visible everywhere here: reduced palettes, the return of black as a constructive color, large planar separations, and ruthless cropping that replaces anecdote with design. Lorette served not as a narrative subject but as a reliable index of how the painter’s system behaved under changing conditions—different blouses, shawls, headgear, poses. “Head of Lorette with Curls” sits near the center of that enterprise. It compresses the discoveries of the series into a single, close-cropped head-and-hand configuration where every element has work to do.

The Crop and the Stage

Matisse pushes the head nearly to the canvas edges. Hair fuses with background into adjoining black fields that frame the face like parentheses. The hand enters from the left, cropped at wrist and knuckles, so the viewer experiences the supporting gesture without getting lost in anatomy. There is no furniture beyond the faint suggestion of a collar; no interior to distract; not even the full sweep of her shoulders. This stringent crop modernizes the portrait and intensifies its psychological effect. It also shifts the painting’s task from describing to organizing. The canvas becomes a stage where a few actors—eyes, nose, mouth, hand, hair, curls—perform an exacting choreography.

The Curls as Calligraphy and Crown

The title’s curls are more than pretty details. They form a dark, looping glyph across the lit plane of the forehead, activating that otherwise calm expanse. Their rounded rhythm echoes the oval of the face and foreshadows the later cut-outs, where a single curved piece could stand for a leaf or wave. Here the curls balance the strong vertical of the nose and the diagonal of the hand, asserting a counter-tempo that keeps the composition from freezing. Matisse paints them not as tiny strands but as a sculptural relief—thick, black strokes whose edges catch light—so they read as architecture rather than ornament.

Color as Climate

The palette is intentionally narrow. Flesh is a warm, benedictory mixture of ochre, pink, and muted coral that gathers most of the light. The background and hair are nearly one continuous, absorbing black with olive undertones that soften the transition into skin. A faint green-gray in the garment’s collar cools the lower edge and prevents the head from floating. The single saturated accent is the mouth—a darker, slightly bluish red on the upper lip and a warmer red below—calibrated to glow without grabbing control. This restrained climate allows value and line to take over expressive duty, delivering calm and clarity instead of chromatic drama.

Black Contour as the Portrait’s Carpentry

One of Matisse’s wartime breakthroughs was to use black not as shadow but as a structural color. In this picture black acts like carpentry. It draws the eyebrows in decisive arcs, rims the eyelids with an elastic line that thickens and thins with pressure, and traces the nostrils and philtrum with economy. It defines the mouth’s outline, the hand’s knuckles, and the hair’s boundary as it slides across the cheek. Because these lines vary in speed, thickness, and opacity, they never harden into a cartoonish outline. They remain alive as drawing, holding the planes in place while leaving the paint’s breath visible.

The Architecture of Planes

Matisse models with large, legible planes. The forehead reads as a broad, slightly curved slab that turns calmly into temple and hairline. The nose is a clean wedge, its bridge moving in a single downward glide to a delicately pinched tip. The cheeks are not fussed; they tilt forward like shallow shields. Even the hand is a series of blocks—the thumb’s cylinder, the knuckle’s facets, the palm’s triangular wedge—stitched by a few black seams. This architectural approach reflects the sculptor’s habit: build the big forms first, place decisive edges, then let small variations emerge from the pressure of the brush rather than from fussy modeling.

The Eyes: Suspense, Not Sentiment

Lorette’s eyes anchor the portrait. They are similar in size but not identical in placement or lighting. The sitter’s left eye carries a darker lid and a fuller shadow under the brow, while the right eye opens slightly wider, catching more light in the inner white. This asymmetry prevents the mask-like stillness that symmetry can induce. The expression becomes a suspended thought rather than a pose. Tiny, triangular highlights and pale passages at the inner corners imply moisture without miniaturist polish, and the thick upper lids keep the gaze weighty. The eyes hold; they do not perform.

Gesture of the Hand

The propping hand is essential to both psychology and design. Conceptually, it proposes a resting mind, time taken to think, a measured distance from the viewer. Structurally, it introduces diagonals and a second set of planes that counter the face’s verticality. Matisse resists the temptation to detail fingers. He presents the hand as a compact block whose pressure slightly compresses the cheek, explaining the face’s soft indentation with a few authoritative, luminous strokes. That physical contact binds model and picture space, making the portrait feel embodied and present.

Light Without Theatrics

Illumination arrives as a broad, diffused presence rather than as a spotlight. The forehead brightens slightly toward its center; the nose ridge carries a controlled highlight; the lower lip picks up a cool glint; the cheek under the hand darkens modestly. These measured transitions prevent soap-opera drama and keep the emphasis on structure. Light clarifies relationships instead of staging them. The background remains nearly value-flat, a blank field that lets small shifts in the face register fully.

Brushwork That Tells the Truth

Close looking reveals Matisse’s honesty about materials. Flesh passages are laid in sweeps that follow form; where he changes hue or value he often lets a ridge of paint remain, recording the moment of decision. In the hair the brush runs dry at the edges, dragging black over warm underpaint to create ragged borders that read as live strands. The hand’s knuckles gather creamy impastos that catch real light, while the garment’s collar is a thin, cool wash, deliberately underplayed to keep attention on the head. The surface never vanishes into illusion; it keeps reminding you that this presence is built from colored paste, moved by a measured wrist.

The Role of the Background

The ground is an ochre field tempered by gray and olive, neither flashy nor dead. It sets mid-value calm against which the face can operate in both directions—up into light and down into shadow. The nearly monochrome background also advances the iconic quality of the image. Like Byzantine grounds that refuse worldly space, Matisse’s neutral field resists deep illusion and keeps attention on the orchestration of forms right at the picture plane.

Psychological Nearness Through Spatial Economy

Because there is so little “room” around Lorette, the viewer experiences the portrait at conversational distance. The hand resolves just a few inches from the picture surface; the mouth sits within reach; the eyes are level. Without props or narrative accessories, the painting registers thought by spacing, pressure, and tiny adjustments of plane. The result is immediate without feeling invasive. It is a portrait that asks to be studied slowly, the way you read a face in real life rather than scrolling past it.

How the Curls Organize the Whole

Return to the curls and watch how they manage the composition. Their arabesque nests under the hair’s heavy arc, echoing it at a smaller scale. Their ends point toward each eye, creating an invisible triangle that binds the upper half of the face. Their scalloped shadows interrupt the forehead’s broad plane to keep it from becoming a blank billboard. They even rhyme with the curve of the upper lip, linking forehead to mouth by a chain of echoes. Without those curls the portrait would still be strong; with them it gains melody.

Between Fauvism and Nice

Painted in 1917, the work sits between the blazing Fauvism of a decade earlier and the decorative interiors of the Nice years soon to come. From Fauvism it retains the courage to let color-state and line carry expression. From the Nice period it anticipates the pleasure in simplified, frontal heads and the calligraphic handling of black. Yet it is more severe than the later odalisques, more focused, and more ethically “quiet.” The painting argues that calm and restraint can be as modern as chromatic excess.

Dialogues With Tradition, Spoken in a Modern Accent

The frontal face, the strong contour, and the barely differentiated ground recall icons and Renaissance busts. But Matisse’s modern accent is unmistakable: radical crop, outline used as a color, planar reduction that refuses photograph-like finish, and an insistence that the painting be both a person and a designed surface. The long echo of Ingres—his belief in line as the sovereign of form—can be felt in the eyebrows and nose, but Matisse’s line is more variable, more physical, less obedient to contour alone. He lets line carry weight and speed, not just description.

The Ethics of Reduction

To simplify a face is to risk cruelty or cliché. Matisse avoids both by keeping each reduction responsive to structure. He drops ears, jewelry, and background detail, but he preserves the asymmetry that signals real presence, the slight torque of the mouth, the pressure of the hand, the seam where nose meets cheek. Simplification serves attention; it does not evacuate personality. The ethical outcome is a portrait that feels respectful and lucid rather than generalized.

A Practical Lesson for Painters

From this canvas painters can learn specific, transferable practices. Build heads with large planes and let elastic black lines carry the key pivots. Reserve saturated color for a single accent—the mouth—so the flesh remains luminous. Use cropping to bring psychological intensity without mere drama. Let the supporting hand be blocky and structural, not an anatomical demonstration. Keep the ground simple but alive so edges breathe. Above all, allow drawing and paint-handling to remain visible; truth of touch equals truth of presence.

Why the Painting Endures

“Head of Lorette with Curls” endures because it holds two truths at once. It reads instantly as a person in a particular thinking mood, yet it also reads as an ordered set of relations—light to dark, curve to wedge, mass to line—that would satisfy even if the subject were anonymous. That doubleness gives the work its staying power. You can love it as portrait and as painting simultaneously, and each viewing toggles between those pleasures without strain.