Image source: wikiart.org

First Impressions: A Face Built from Light and Line

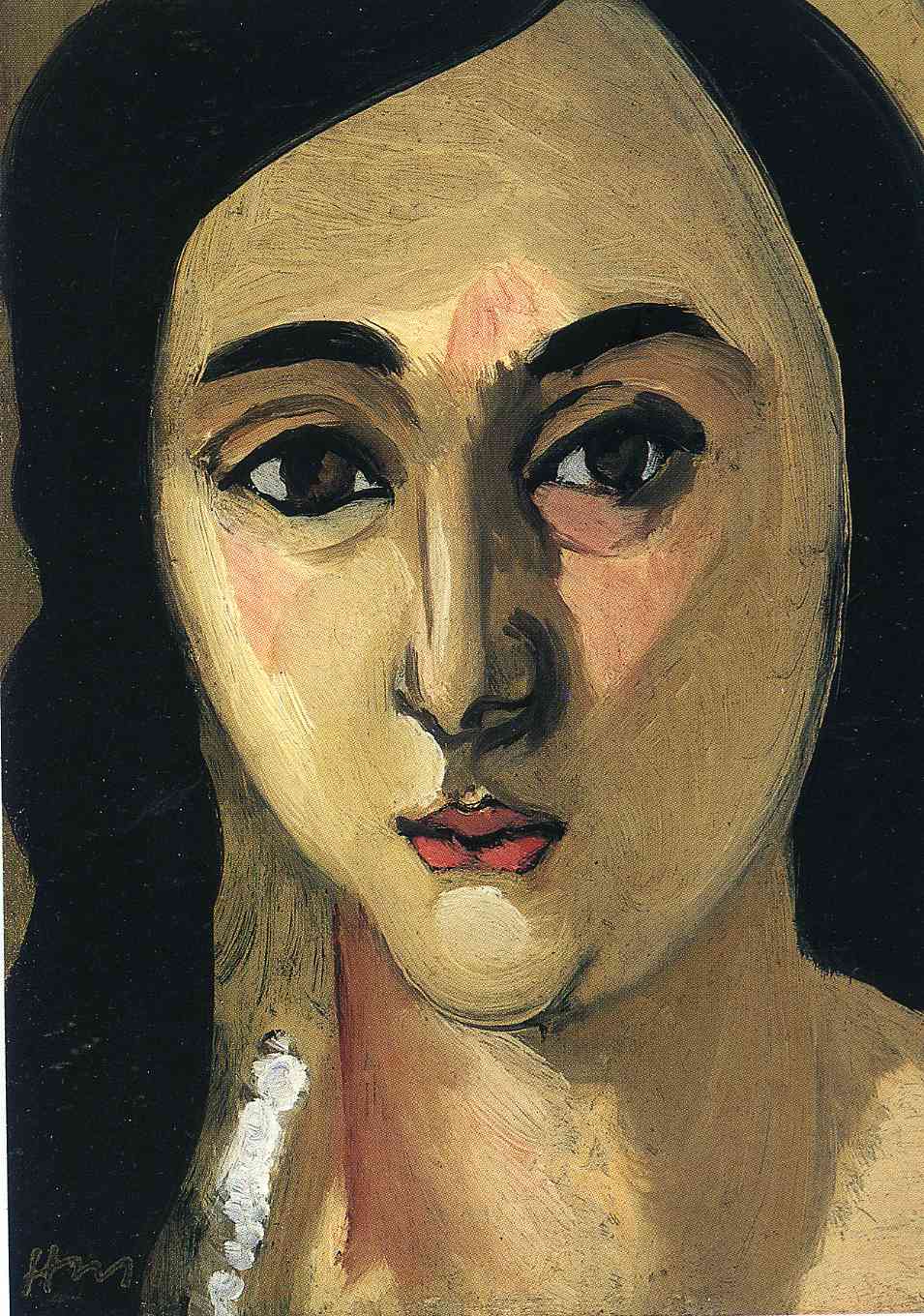

Henri Matisse’s “Head of Lorette” (1917) grips the viewer by eliminating everything except what the painter considers essential. There is no room, no chair back, no patterned shawl, hardly even shoulders—only a face, cropped close, presented as a field where light, shadow, and decisive contour negotiate identity. The model’s slightly parted lips and steady, sidelong gaze create a mood that is at once intimate and monumental. The black curtain of hair on either side reads as two great parentheses that hold the portrait in place, while the warm planes of the forehead, nose, and cheeks advance toward us with an almost sculptural firmness. The painting is not a descriptive likeness so much as a concise grammar for how a face can be built from a handful of well-chosen moves.

Lorette as Muse and Method

Lorette, Matisse’s frequent model across 1916–1917, appears in dozens of portraits and figure studies. She is less an anecdotal personage in these canvases than a reliable instrument for a new language. During the war years Matisse had moved from the blazing primaries of Fauvism toward a disciplined approach that relies on black as a constructive color, on large value separations, and on reduced, legible shapes. “Head of Lorette” is a peak statement of that method. The model’s face becomes a site to test how much can be said with how little—how a handful of planes, two dark arcs for brows, and the unerring placement of a mouth can carry presence.

The Architecture of the Crop

The composition’s first surprise is how close Matisse cuts. The head fills the rectangle almost to breaking. Hair and background fuse into a single black field that trims the oval of the face, tightening it like a medal in a mount. The left edge shears off strands of hair and a sliver of shoulder; the right edge slices the hair mass with similar bluntness. This cropping does three things at once. It modernizes the portrait by refusing salon-distance; it abstracts the head into a designed oval framed by dark; and it focuses attention on the center of the face, where light turns with the crispness of carved stone.

Color as Climate: Warm Flesh, Cool Dark

The palette is intentionally spare. Flesh is organized into a warm buff modulated toward peach around the cheeks and toward ivory along the ridge of the nose and the philtrum. A delicate coolness enters at the shadow under each eye and under the lower lip, preventing the warmth from thickening into heaviness. The hair and background are a deep, absorbing black with the slightest hints of brown and olive caught at the edges. A measured rose sits in the lips, more blue on the upper lip and warmer below, whose saturation is restrained so that the mouth glows without detaching from the face. The few color notes feel inevitable; they are chosen not for prettiness but to keep the head breathing within its black surround.

Black Contour as the Portrait’s Carpentry

Around 1916–1917 Matisse reintroduced black not as shadow but as an organizing color. In “Head of Lorette” black behaves like carpentry. It draws the eyebrows as single, arcing strokes that thicken at the center and thin toward the temples, anchoring the gaze. It rims the eyelids with an elastic line that holds the whites in check and compresses the irises into dark almonds that gleam at their inner corners. It traces the nostril wings, then flares outward to articulate the curve of the lips and the break between upper and lower lip. Because these blacks are applied with visible pressure, thickening and tapering like penmanship, they refuse the look of diagram and remain alive as drawing.

Planes and Axes: A Sculptor’s Eye

Matisse’s frequent sculptural work in this period informs the way planes are modeled. The centerline of the nose is a ridge where light glances downward; its right plane is set with one suppled sweep while the left receives a cooler shadow that describes the bridge and brow. Cheek and jaw are constructed as large, calm surfaces with minimal inflection, and their slight asymmetry—more light on the sitter’s left cheek, more shadow along the right jaw—gives life to the turn of the head. The mouth is centered, but the left corner lifts almost imperceptibly, less a smile than a tremor of thought. Nothing is fussed. Planes read like decisions, not like labor.

The Eyes: Suspended Between Directness and Reserve

The eyes are the picture’s fulcrum. They look a fraction off-center, neither confronting the viewer head-on nor floating into dream. The dark rim of the upper lids and the thickened inner corners create a weight that keeps the irises steady. A small, triangular highlight in each eye and a lighter patch along the inner whites provide the illusion of moisture without retreating into small-detail illusionism. These touches suggest intelligence and inwardness without sentimentality, and they keep the gaze from going glassy. The eyes do not narrate; they hold.

Light as a Quiet Event

No dramatic spotlight falls on Lorette. Light feels like a broad, diffused presence that clarifies form rather than performs. A soft illumination along the forehead culminates in a pale, almost rectangular patch between the brows, a decision that asserts the plane without pretending to photographic verisimilitude. A quick stroke under the lower lip, cooler and whiter than the surrounding flesh, sets the mouth forward and gives the face its sense of breath. The neck receives enough value difference to turn, then disappears into the blackness, ensuring that the head is the only stage.

Brushwork That Keeps Its Body

Close looking reveals that Matisse leaves the paint with its physical presence. Flesh tones are laid with loaded, slightly curving passes that record wrist motion. Where he shifts hue—from warm cheek to cooler under-eye—he simply pulls one color over another, allowing a ridge to remain. Along the hairline the brush sometimes runs dry, producing a ragged border that reads as fine wisps without the need to paint individual hairs. The material honesty prevents the picture from becoming too sweet; we are invited to witness the making, not just the result.

The Role of Whiteness

White punctuates and calibrates. It burns at the highlight on the nose ridge and at the damp lower lip, glints in the inner eyes, and appears unexpectedly as a beaded note along the left shoulder, perhaps a suggestion of lace or the edge of a chemise. These whites are not merely light; they are compositional beats that keep the warm tones from pooling and the black fields from swallowing the figure. They are small and strategic, like the high notes in a low register melody.

Reduction Without Loss

One of the painting’s triumphs is how much emotion remains after so much editing. The dress is barely present; the hair is a single mass; ears are omitted; even the neck is an afterthought. Yet the portrait feels complete because what survives is the relational core: the oval of the face against the night of hair, the dark architecture of brows and eyes, the pivot of nose and mouth, and the slight lift of the left cheek that registers a pulse of attention. Matisse shows that a portrait does not need to inventory features; it needs to orchestrate forces.

A Dialogue with Tradition, Spoken in a Modern Accent

“Head of Lorette” converses with traditions Matisse admired—Byzantine icons, Florentine portrait busts, and the planar simplifications of Ingres—without imitating them. The frontal, almost iconic stance and the reliance on contour echo sacred prototypes, while the warm-to-cool modeling of the nose and cheeks gestures toward classical draftsmanship. But the modern accent is decisive: extreme crop, monochrome surrounds, and the refusal of tiny descriptive labor in favor of structural clarity. The result is a face that feels ancient and contemporary at once.

Psychological Nearness through Spatial Economy

The psychological intimacy comes not from demonstrative expression but from the collapse of space. By pushing the head close to the picture plane and denying room for the torso or environment, Matisse makes the viewer share the sitter’s air. The black field surrounding the face is less background than silence—the quiet against which the portrait’s few notes sound. This nearness is not aggressive; it is measured and calm, the way one might lean forward to catch the exact shape of a thought crossing someone’s face.

Wartime Clarity and the Search for Balance

Painted in 1917, the work partakes of a wartime ethic that Matisse articulated often: an art that offers balance, clarity, and repose. The portrait is not escapism; it is discipline. Every stroke counts, color is tuned rather than shouted, and the drawing’s authority allows tenderness to appear without theatricality. In an anxious year, this kind of pared-down exactness reads as a moral stance: to order what can be ordered, to clarify what can be clarified, and to hold steady attention on a human face.

Comparisons Across the Lorette Series

Seen alongside other Lorette paintings—seated portraits in blouses, images with turbans, profiles with green shawls—this head stands out for its monastic focus. Many canvases frame Lorette with textiles and patterned cushions; here the ornament is removed so that the instrument can be heard alone. The same eyebrows, the same measured mouth, the same slightly forward tilt recur across the series, yet in this head they crystallize into emblem. The painting becomes a key to the whole sequence: this is the underlying structure from which the elaborate settings will later bloom.

The Mouth as a Measure of Humanity

Matisse has always been careful with mouths. In “Head of Lorette” the mouth serves as a measure of the whole person. Its outline is not a smooth bow but a living line: the upper lip a dark, cool plane that sinks under light; the lower lip a warmer, fuller form that catches a highlight at its rim. The slight part suggests a breath or a word withheld, nothing theatrical, just the body’s readiness to speak. That readiness—poised but restrained—sets the portrait’s emotional temperature.

The Hair as Architecture and Frame

The black hair performs sculptural duty. Pulled into a heavy fall on both sides, it narrows the face at the temples, deepens the shadows around the eyes, and protects the lighted planes from dissipating into the background. Where the hair meets skin, Matisse creates a thin, ambiguous border—sometimes a hard edge, sometimes a dry-brush fringe—so that the transition feels both graphic and tactile. The hair is not an inventory of strands; it is a building that houses the face.

How to Look Longer

One way to extend time with the painting is to track asymmetries. Compare the eyebrows: the sitter’s left brow curves higher and is slightly thicker; the right is straighter, pressed by the brow ridge. Notice that the left eye’s inner corner is warmed by a reddish half-moon, while the right carries a cooler shadow. Follow the nose: the bridge bends minutely toward the sitter’s left, and a soft, triangular patch of rose sits between the brows. Then move to the edges: see how the flesh meets black differently on each side, crisp at the right jaw, softer at the left where a glint of white bead punctuates the shoulder. Each small imbalance keeps the portrait alive; perfect symmetry would have deadened it.

Material Particulars and the Honesty of Making

There is no varnish of concealment here. The canvas grain participates in the flesh’s texture, and the direction of the strokes aligns with the forms they build. Where Matisse shifts from one tone to another he does not always blend; a ridge of paint may mark the seam, a record of the hand that stabilizes the structure. The black around the face varies in density—opaque in some regions, thinner elsewhere where the ground breathes through—so the void itself has life. The picture remains a made object, not a window, and that material candor is central to its impact.

Enduring Significance

“Head of Lorette” endures because it proves that a portrait can be both minimal and humane. It demonstrates that a few clear relations—light to dark, warm to cool, contour to plane—are sufficient to anchor presence. The painting reads instantly from a distance and rewards prolonged, close attention; it is both diagram and person. Many later artists, from the School of Paris to contemporary painters of compressed heads, draw on this discovery: that the face is not a list of features but a designed field where attention and empathy can be organized.