Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Munch’s Berlin Years and Psychological Exploration

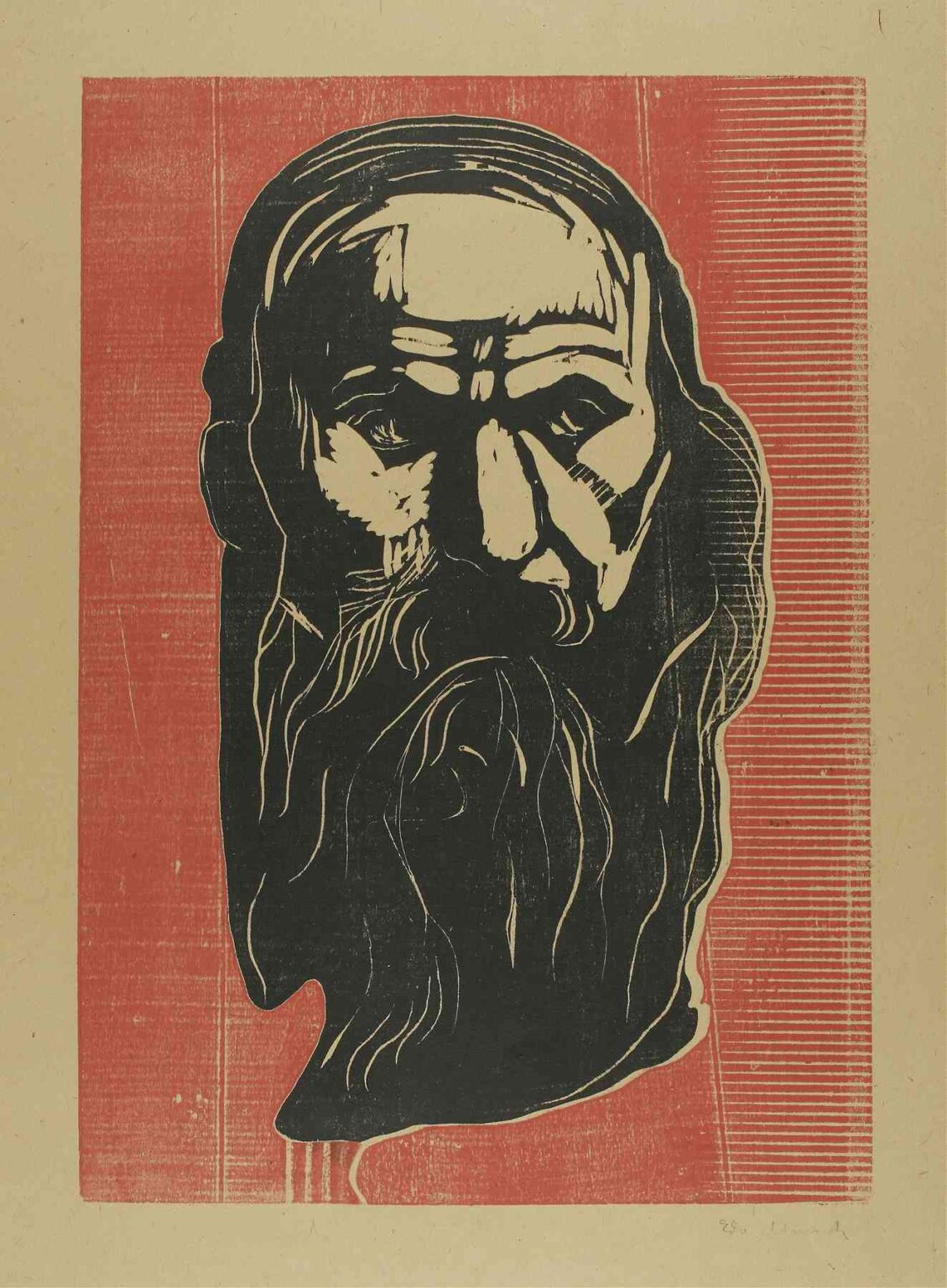

By 1902, Edvard Munch (1863–1944) had firmly established himself as one of Europe’s foremost Expressionist innovators. After the shockwaves caused by The Scream (1893) and the Frieze of Life series, he moved from Kristiania (now Oslo) to Berlin in 1892, immersing himself in the city’s avant-garde art circles. In Berlin Munch experimented with lithography, woodcuts, and tempera on paper, exploring themes of anxiety, isolation, and the life cycle. “Head of an Old Man with Beard”, executed as a woodcut in 1902, reflects this ongoing preoccupation with inner states. Rather than focusing on dramatic color or swirling forms, the work pares down subject matter to a meditative study of age, mortality, and character, using the stark contrasts and linear energies unique to monochrome printmaking.

Subject Matter: Portraiture Beyond Naturalism

At its core, “Head of an Old Man with Beard” is a portrait of an elderly male figure—his long beard cascading into the composition’s lower half, his furrowed brow and sunken eyes evoking weariness and contemplation. Munch eschews naturalistic detail in favor of expressive line: heavy black contours carve out facial features, while thinner, rhythmic incisions suggest hair strands and skin folds. The man’s eyes, deep-set and shadowed, seem simultaneously resigned and vigilant. Though Munch provides no clues to identity—no name, setting, or garb beyond the suggestion of a loose cloak—the work radiates universal resonance. This anonymity invites viewers to project broader themes of aging, wisdom, and existential solitude onto the figure.

Composition and Spatial Dynamics

Unlike conventional portraits set against neutral or interior backgrounds, Munch positions his old man against a textured red-brown ground, itself overlaid with vertical and horizontal grain lines from the woodcut block. The head nearly fills the vertical axis, cropping just below the shoulders to focus attention on facial expression and beard. The beard’s sinuous curves echo the woodgrain patterns, creating a visual dialogue between figure and background. Munch off-centers the head slightly to the right, counterbalanced by denser line work on the left beard area, subtly guiding the viewer’s gaze from the forehead down through cascading beard strands. This compact yet dynamic composition transforms a static head study into a rhythmic interplay of shape and void.

Palette and Tonal Contrast

Although “Head of an Old Man with Beard” is monochromatic, its tonal range is surprisingly rich. The primary black relief print stands out against the warm, earthy reddish-brown background—achieved by inking a separate block or hand-tinting the paper. The man’s skin emerges in pale negative space, emphasizing axes of highlight on brow ridges, nose bridge, and beard. Deep blacks define eye sockets, hairline, and hollow cheeks. Mid-tones appear where black ink is thinned or where the woodcut’s grain transfers only partially. Munch leverages the stark interplay of black, brown, and paper white to heighten the psychological immediacy: age lines and beard textures become rituals of shadow and light.

Printmaking Technique: Woodcut as Emotional Tool

Munch embraced woodcut printing as a means to merge drawing spontaneity with the reproducible possibilities of graphic art. In “Head of an Old Man with Beard,” he carved two blocks: one for the red-brown background and one for the black head lines. The woodcut grain remains visible across flat areas, imparting a tactile authenticity. Deep gouges define contours, while shallower cuts produce fine hairlines and cross-hatching textures. Slight misregistration between blocks—where black lines occasionally overrun or fall short of red edges—was intentional, lending a vibratory energy to the composition. This visceral hand-crafted quality makes the portrait feel at once raw and resonant, as if the old man’s presence is emerging from the wood itself.

Line, Form, and Expressive Anatomy

Munch’s line work in this portrait balances economy with emotional power. Broad curves outline the skullcap and cheekbones, while delicate swirls trace the beard’s individual hairs. Facial wrinkles—deep on forehead, near eyes, and around mouth—are rendered in chopped, angular strokes that suggest life’s accumulated sorrows. Yet these lines are not purely descriptive; they carry expressive weight, echoing Munch’s lifelong interest in anatomy as psychology. Through minimal marks, he conveys the tension of age: the upward curve of a brow ridge might suggest frowning concern, while a swirling beard line hints at the slow passage of time.

Symbolism and Thematic Depth

In Munch’s symbolic vocabulary, beards often stand for wisdom, maturity, and the burden of experience. Here, the old man’s beard dominates the lower canvas, as if representing the accumulated weight of years. The cropped forehead and intense gaze may symbolize intellectual reflection, while the beard’s engulfing curls could imply emotional complexity. The reddish-brown background, reminiscent of earth or rust, anchors the figure in mortality and impermanence. In the context of Munch’s broader mythopoetic world, this portrait becomes a meditation on the final stages of life: a liminal space between presence and absence, reflection and dissolution.

Relation to Munch’s Oeuvre and the Frieze of Life

While Munch’s Frieze of Life series famously charts love, anxiety, illness, and death, “Head of an Old Man with Beard” represents an intimate offshoot: the artist’s continued focus on existential themes distilled into graphic form. Unlike the swirling Symbolist backgrounds of The Scream or Madonna, this print offers no narrative setting, reinforcing its universality. It foreshadows Munch’s later woodcuts of bathers and self-portraits in its directness and economy. Moreover, the work bridges his earlier tempera portraits of friends and acquaintances with his darker Expressionist prints of the early 20th century, revealing a continuum in his exploration of human psychology.

Provenance and Publication History

Munch printed “Head of an Old Man with Beard” in a limited edition of approximately 30 impressions in 1902. Early impressions were distributed via the journal Zeitschrift für bildende Kunst and private exchanges among Berlin avant-garde circles. After Munch’s death, many prints entered the holdings of the Munch Museum in Oslo. Over the past century, collectors have prized early impressions for their rich, hand-tinted backgrounds and crisp black lines. The print’s exhibition record spans major retrospectives in Oslo, Berlin, New York, and Tokyo, where it has been showcased as emblematic of Munch’s mastery of monochrome media.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

Contemporary critics in the early 1900s received the print with interest, commending Munch’s bold line work but often noting its departure from the rich colorism of his paintings. Mid-century scholars revalued his graphic output, recognizing woodcuts like “Head of an Old Man with Beard” as pivotal to Expressionism’s development. Recent scholarship emphasizes the print’s psychological directness: art historians such as Reinhold Heller and Kalle Løchen interpret the work as a schematic map of emotional territory, where beard lines denote neural pathways of memory and loss. Feminist scholars have explored gendered readings—how the elderly male visage simultaneously commands authority and reveals vulnerability—opening fresh interpretive angles on Munch’s iconography.

Legacy and Influence on Graphic Arts

Munch’s innovative woodcuts have inspired generations of printmakers who seek to infuse figurative work with psychological depth. German Expressionists such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff cited his monochrome portraits as models for the “primal” power of black-and-white linear art. Contemporary artists working in linocut and monotype continue to reference Munch’s register play—intentional misalignments of color blocks and woodgrain textures—to heighten atmosphere. “Head of an Old Man with Beard” in particular influenced 20th-century explorations of aging in art therapy contexts, where line work becomes a diagnostic of emotional states.

Conservation Considerations

Early impressions of “Head of an Old Man with Beard” were printed on Japanese Gampi paper, prized for its translucency but fragile in acidic Western collections. Conservation efforts have focused on deacidification of backing materials and stabilization of the red-brown ground, which can flake if surface oils invade paper fibers. Modern restorations employ Japanese tissue infills and reversible adhesives to mend tears. Framing under UV-filtering glass preserves both the black ink and the delicate hand-tinting, ensuring that future generations can experience Munch’s original tonal subtlety.

Conclusion: A Universal Study of Aging and Existence

Edvard Munch’s “Head of an Old Man with Beard” (1902) transcends its medium to become a powerful meditation on the human condition. Through spare yet expressive woodcut lines, Munch captures age’s physical markers and the weight of memory. The limited palette of black set against red-brown amplifies emotional resonance, while the cropping and composition distill the portrait to its most essential elements. In its anonymity, the old man becomes an archetype—every man who has aged, who has known sorrow and introspection. As both a technical tour de force in printmaking and a poignant exploration of existential themes, this work stands among Munch’s most profound graphic achievements, reminding viewers that portraiture can lay bare the universal rhythms of life and time.