Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction to Peter Paul Rubens’s “Head of an Old Man”

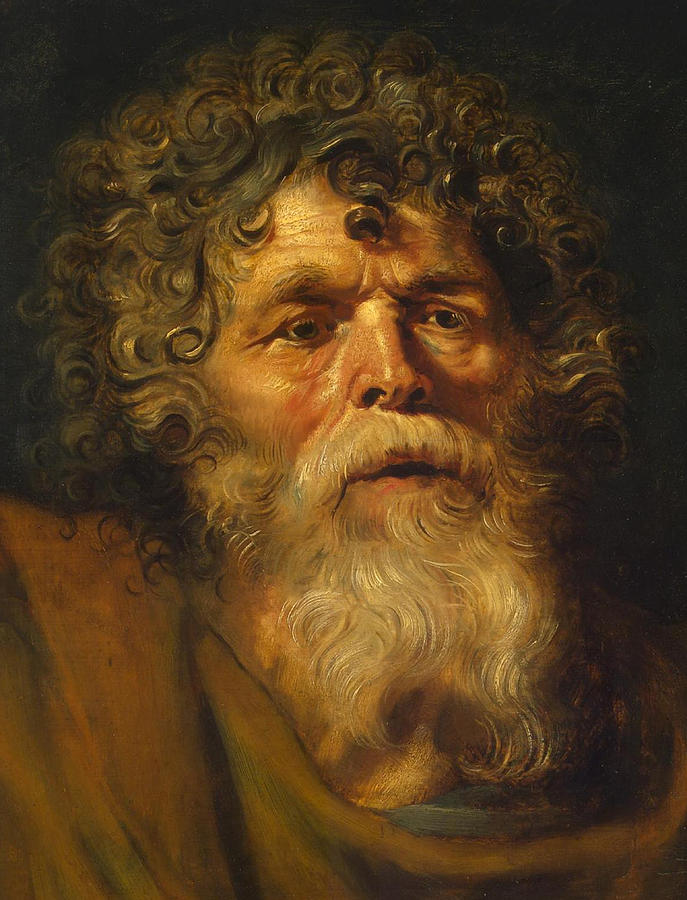

“Head of an Old Man” by Peter Paul Rubens is a compact but extraordinarily powerful study of age, emotion, and human character. Rather than depicting a specific saint or ruler, Rubens focuses solely on the weathered face of an elderly man with a wild mane of curly hair and a flowing white beard. The figure wears a simple brown cloak; the background is a deep, velvety darkness that pushes the illuminated head forward.

Paintings like this are often called tronies: not portraits in the strict sense, but character studies that explore expressive physiognomies, dramatic lighting, and painterly effects. Rubens used such studies as reservoirs of motifs for larger religious or historical works, where a similar head might become an apostle, prophet, philosopher, or beggar. Yet “Head of an Old Man” stands on its own as a self-sufficient image. It captures a moment of intense, almost stunned contemplation, as if the man has just witnessed something overwhelming or is wrestling with a deep inner turmoil.

The Expressive Power of the Face

The face dominates the composition. Rubens crops the canvas closely so that the viewer encounters the old man at near life-size, eye-to-eye. The man’s features are deeply etched: furrowed brow, sunken cheeks, and heavy eyelids that partially veil his gaze. His mouth is slightly open, revealing a hint of teeth and suggesting that he may be in mid-breath or mid-sentence.

This open mouth is crucial. It introduces a sense of vulnerability, of something unfinished or unguarded. Combined with the lifted eyebrows and wide-set eyes, it creates an expression that can be read in multiple ways: astonishment, sorrow, awe, or even a kind of dazed exhaustion. Rubens intentionally keeps the emotion ambiguous, allowing viewers to project their own narratives onto the face.

The skin is modeled with extraordinary sensitivity. Warm reds and oranges glow beneath the surface, especially around the nose, cheeks, and eyelids, hinting at age-thinned skin and the underlying network of blood vessels. Cooler tones define the hollows of the cheeks and the shadowed areas near the neck. This chromatic complexity makes the flesh feel alive despite the overall sense of weariness.

Hair, Beard, and the Drama of Texture

One of the most striking elements of “Head of an Old Man” is the luxuriant hair and beard. Rubens revels in the opportunity to paint wild curls and swirling strands. The hair tumbles in dense, looping locks around the forehead and temples, catching small highlights that describe each curl’s movement. The beard, by contrast, flows downward in softer, wavy strands of white and pale grey.

The interplay between the darker, tightly coiled hair and the lighter beard adds visual rhythm. It also sets up a symbolic contrast: the unruly vitality of the hair versus the snowy, aged wisdom of the beard. The curls can almost be read as external manifestations of inner turbulence, while the beard gives the figure gravitas.

Rubens’s brushwork here is bold and visible. He lays down strokes that both describe individual strands and fuse into masses of texture. In places, the paint seems almost sculpted, catching the light like relief carving. This tactile quality contributes to the Baroque sense of immediacy. The viewer not only sees but almost feels the roughness and softness of the hair.

Chiaroscuro and the Baroque Stage of Light

The painting is a superb example of chiaroscuro, the dramatic use of light and shadow that became central to Baroque art. The background is nearly black, with only subtle variations suggesting depth. Against this darkness, the old man’s head emerges like a spotlighted actor on a stage.

Light falls primarily from the upper left, striking the forehead, nose, cheeks, and upper beard. The right side of the face recedes into heavier shadow, although Rubens allows just enough illumination to keep the features legible. The transitions between light and dark are handled with great sensitivity; they are neither abrupt nor overly smooth, but modulated to enhance the contours of the face.

This lighting does more than model form. It creates psychological atmosphere. The darkness behind the man can be read symbolically as the unknown, the past, or approaching death, while the light that touches his face suggests a moment of revelation or insight. The overall effect is one of spiritual drama. Even though the painting does not explicitly depict a religious subject, it feels imbued with a sense of encounter with something larger than the self.

Costume and Timeless Identity

The old man wears a simple brown cloak or mantle draped around his shoulders. Rubens renders it with broad, sweeping strokes of ochre and golden-brown, allowing folds and creases to emerge from the movement of the brush rather than from painstaking linear detail.

This rough, generic garment is intentionally nonspecific. It provides just enough information to anchor the head in a human body, but it does not identify the sitter as belonging to a particular social class or historical moment. He could be a philosopher of antiquity, a biblical patriarch, a contemporary peasant, or a wandering hermit.

This deliberate ambiguity makes the figure timeless and universal. Rubens is less interested in recording an individual’s fashion than in using costume as a neutral frame for the face. The cloak’s earthy tones also harmonize with the warm palette of the flesh, linking man and garment to the same material world.

Tronie or Portrait? The Function of the Study

The label “Head of an Old Man” suggests that this painting is a tronie or character study rather than a commissioned portrait. Tronies were essential tools in Rubens’s workshop practice. By building up a stock of expressive heads, the artist could insert convincing characters into biblical, mythological, and historical scenes without needing live sitters for every figure.

The intensity of expression and dramatic lighting in this work are exactly suited to such uses. A head like this could easily become that of an apostle in an altarpiece, a prophet listening to divine speech, or a philosopher engaged in argument. The vagueness of costume and setting made the study adaptable to many narratives.

However, the painting’s completeness and emotional power allow it to transcend its functional origin. Even if Rubens originally intended it as a study, he endowed it with enough depth and polish to stand alone as an independent artwork. Viewers today often value such studies precisely because they show the artist’s hand and imagination at their most direct and unmediated.

Psychological Interpretation: Age, Experience, and Vulnerability

“Head of an Old Man” invites psychological reading on several levels. The subject’s advanced age is evident in the grey beard, the sagging skin, and the weary eyes. Yet there is no cynicism or bitterness in his expression. Instead, there is a sense of openness, almost of childlike surprise.

This combination of age and vulnerability is poignant. It suggests a life full of experiences, perhaps hardships, culminating in a moment where the man confronts something that still has the power to astonish him. That “something” could be religious—an encounter with God, a sudden spiritual insight—or it could be more mundane, like sudden news or an emotional revelation.

The open mouth and slightly furrowed brow intensify this effect. They make it seem as if the man is about to speak, but the words have not yet formed. Rubens captures him at the threshold between thought and utterance, where inner feeling is visible but not yet fully articulated. That uncertainty is precisely what makes the study so compelling.

Rubens’s Humanism and Study of Character

Rubens was deeply influenced by humanist ideas and classical literature. As a reader of ancient authors and a traveler in Italy, he absorbed the notion that art could explore the full range of human passions and types. “Head of an Old Man” fits squarely within this tradition.

Rather than idealizing the figure, Rubens revels in the particularities of the old man’s face: the irregular nose, the heavy lower lip, the asymmetry of the eyes. At the same time, he elevates these particulars into a kind of archetype of aged masculinity. The painting communicates not just “this man” but “what it means to be an old man” in a broader sense.

That duality—individual and universal—is central to Rubens’s humanism. He respects the dignity of this specific being while also using him as a vehicle for exploring broader truths about time, mortality, and emotion. This is why the painting can speak to viewers across centuries who have no idea who the model was, or if he even had a name.

Painterly Technique and the Energy of the Brush

From a technical perspective, “Head of an Old Man” is a showcase of Rubens’s mature painterly style. The paint handling is vigorous yet controlled. In the hair and beard, he uses swirling, almost calligraphic strokes that mimic the movement of curls. In the face, he blends colors more delicately, but still allows the direction of the brush to follow the form.

Glazes and opaque passages interlock to create depth. Thin, transparent layers add warmth to the shadowed areas of the cheeks and temples, while thicker, more opaque strokes build up the highlights on the forehead, nose, and beard. The result is a surface that seems to pulse with life, as if light were not merely falling onto the skin but emanating from within it.

The background shows traces of underpainting and revisions, evidence of the artist’s process. These visible workings undercut any sense of slick finish and remind us that the image was constructed through experimentation and adjustment. For many modern viewers, this immediacy is part of the painting’s appeal; it feels like a glimpse into Rubens’s studio practice, a record of his hand thinking in paint.

Relationship to Rubens’s Other Studies of Heads

Rubens produced many studies of heads—young and old, male and female, idealized and grotesque. “Head of an Old Man” relates closely to his studies for apostles and prophets in large altarpieces such as “The Elevation of the Cross” or “The Descent from the Cross.” In those works, similarly rugged, bearded faces express grief, wonder, or fervent faith.

Comparing these pieces reveals how Rubens could adapt a single study to different contexts. The old man’s head might appear as a mourning disciple at the foot of the cross, or as a hermit listening to divine instruction. The underlying expression of astonished gravity remains, but the narrative frame changes its meaning.

At the same time, each head study has its own personality. In this one, there is perhaps more tenderness, more open vulnerability, than in some of the sterner apostolic faces. The soft, almost luminous beard and the gentle sag of the lips lend a certain kindness to the character. That nuance hints at Rubens’s ability to differentiate even among similar types, granting each study its own emotional fingerprint.

Contemporary Resonance and Viewer Response

Today, “Head of an Old Man” resonates with viewers partly because of its honesty. In a culture that often idealizes youth, the painting confronts us with age in all its complexity: the beauty of weathered features, the fragility of skin, the lingering spark of emotion in tired eyes.

Many viewers find themselves drawn to the man’s expression, searching for a story behind his gaze. That open interpretive space is one of the painting’s strengths. It allows the work to function in different contexts—museum, book cover, or private collection—while still inviting personal reflection. The old man can become a stand-in for a wise grandfather, a biblical patriarch, a philosopher, or even a self-image projected into the future.

The painting also offers a lesson in looking. Its close cropping and concentrated lighting encourage viewers to slow down and attend to subtle variations of color and form. The longer one looks, the more the face reveals: tiny shifts in skin tone, highlights in the eyes, the way light catches one particular curl. In this way, Rubens trains the viewer in a more attentive, contemplative mode of seeing.

Conclusion

“Head of an Old Man” by Peter Paul Rubens is a small painting with immense emotional and artistic weight. Through a close-up study of a single weathered face, Rubens explores themes of age, vulnerability, and human dignity. Dramatic chiaroscuro, richly textured hair and beard, and nuanced color modeling combine to give the figure nearly sculptural presence and psychological depth.

Whether originally conceived as a tronie for use in larger compositions or as a self-contained work, the painting exemplifies Rubens’s mastery of character and paint. It captures a fleeting moment when inner feeling becomes visible on the surface of the skin—before words are spoken, before emotion settles into composure.

In this old man’s gaze, viewers can sense a lifetime of experiences distilled into one intense, silent expression. That is why, despite its modest format and anonymous sitter, “Head of an Old Man” continues to captivate and move audiences, standing as a testament to Rubens’s ability to make a single human face carry the weight of universal experience.