Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction: A Wild Face Brought Close

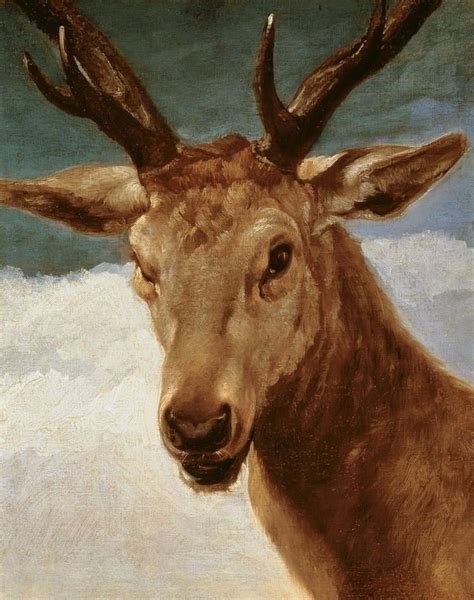

Diego Velázquez’s “Head of a Stag” is a startlingly direct encounter with an animal that, in the court culture of seventeenth-century Spain, signified both nobility and quarry. The canvas presents the stag at bust length and near life-scale, antlers cutting a dark geometry against a cool, cloud-streaked sky. The gaze is frontal, the muzzle moist, the fur laid in quick, tensile strokes that shift with the light. Stripped of narrative and trophies, the picture confronts the viewer with a being rather than a symbol. It is hunting art inverted: instead of the triumph of the hunter, we meet the quiet majesty of the hunted.

Historical Moment and Purpose

Around 1634 Velázquez was deeply engaged with images related to the royal hunt, painting equestrian and sporting portraits as well as scenes and studies for the Habsburgs’ leisure palaces near Madrid. Works like this one likely belonged to that broader project, in which animal life became an essential component of a visual environment that celebrated the outdoors. Yet the picture exceeds decorative function. In a court accustomed to allegory and heraldic pageantry, Velázquez offers an almost scientific attention to the stag’s presence. The head is not a mere attribute beside a prince; it is the subject itself, invested with the painter’s full powers of observation.

Composition and the Architecture of Attention

The composition is disarmingly simple and supremely effective. The stag’s head fills the vertical rectangle, cropping antlers near the frame so that their asymmetrical tines create a syncopated rhythm against the sky. This tight cropping eliminates distractions and draws the viewer into the topography of brow, eye, cheek, and muzzle. The neck enters from the lower right like a diagonal buttress, stabilizing the head’s mass as it turns slightly to the left. A wedge of cloud sets off the warm fur, while a sliver of blue vaults the space above the antlers, extending breath around the animal. Nothing else competes with the face; composition becomes a moral choice to honor proximity.

Light, Air, and the Tonal Climate

Light comes from the left, grazing the antler bases, spilling over the bridge of the nose, and catching in the triangular planes of the cheek. Velázquez avoids theatrical chiaroscuro; the illumination is outdoor and honest, with shadows that remain breathable and articulate. The sky is an active participant, painted in broad, semi-opaque sweeps that fuse with the luminous underpaint of the clouds. This atmospheric handling surrounds the stag with real air. The animal does not float against a neutral backdrop; it inhabits weather. That truth of environment helps the portrait read as a living encounter rather than a studio classification.

Fur as Drawing, Paint as Touch

Velázquez builds the coat from strokes that are both descriptive and abstract. Short, directional marks around the muzzle suggest the stiff whiskers and the change of texture where soft fur meets moist skin. On the forehead, strokes lengthen and curve, following the skull’s form like topographic lines. Along the neck, broader, more fluid sweeps announce thicker hair and deeper shadow. He never itemizes hairs; he orchestrates passages of value and temperature so that the eye completes the texture. The sensation is tactile without pedantry—fur that seems to lie under the hand, responsive to breeze and light.

Antlers: Geometry and Growth

The antlers are not trophies laid flat; they are structures growing from living bone. Velázquez renders their branching with sculptural conviction, the tines emerging as believable cylinders that twist and taper. Their matte surface absorbs light more than it reflects it, a crucial observation that keeps them from turning metallic. Small chips and irregularities are suggested by economical accents, and the attachments at the skull are swollen, veined, and convincing. The antlers’ dark silhouettes also serve compositional ends, mapping diagonals that anchor the head within the sky and frame the eyes as points of psychic intensity.

The Eyes: Alertness Without Sentiment

Animal eyes can tempt sentimentality. Velázquez resists. The near eye is glossy and complex, a pool of deep brown that records the reflection of light without turning into humanized expression. The far eye, set slightly back and shadowed by the skull, is quieter but still alert. Together they create binocular depth that makes the head turn in space. There is no anthropomorphic pleading here, no cartoon drama. The stag appears as a being with its own center of attention, its own calculus of risk and curiosity.

The Muzzle and the Science of Moisture

The nose and mouth are marvels of observation. Velázquez captures the cool sheen of the muzzle with restrained highlights that model soft convexities without hard edges. The nostrils open as dark commas, wet-rimmed, breathing. The parted lips reveal the slightest hint of tooth and tongue, a momentary motion caught without narrative fuss. This subtle animation refuses the taxidermic stillness of many hunting images. The animal is not mounted; it is about to snort, to turn, to step.

Color as Moral Temperature

The palette is limited yet eloquent: warm ochres and raw umbers for fur; cooler browns and grays for antlers and shadow; a sky built from lead-tin whites and blue-gray notes that avoid theatrical ultramarine. The contrast between warm animal and cool heaven reads as a natural sympathy rather than a symbol. In Spanish art of the period, black often stood for dignity; here, brown carries a similar ethic of restraint. Nothing screams. Color works like weather: steady, calm, clarifying.

Brushwork: Suggestion Over Enumeration

Seen up close, the surface reveals how little is needed to convince the eye. The cloud is a few loaded swathes dragged across blue underpaint; the antler edges are single, confident lines softened by a dry touch; the fur is layered from thin scumbles to small impastos that catch light. Velázquez avoids over-finishing, trusting the viewer to reconcile painted shorthand into optical truth at the right distance. That trust is part of the picture’s power. It invites participation—a partnership between seeing and making.

In the Company of Royal Hunts

Within the ecosystem of Velázquez’s hunting imagery—kings and princes in the field, dogs posed with alert patience—“Head of a Stag” acts as a kind of companion piece, a close study of the quarry that dignifies the chase by honoring the animal’s presence. Spanish court culture valued the hunt as a theater of discipline and hierarchy, but it also cultivated a knowledge of landscape and species. The painting reflects that culture of attention. It is not a moralizing lament; nor is it triumphalist propaganda. It is a study that makes skillful, ethical looking a pleasure in itself.

Comparison and Difference with Northern Animal Painting

In the same century, Flemish painters such as Frans Snyders specialized in abundant, often dramatic game pieces—tumbling hares, bursting baskets of fruit, dogs lunging at boars. Velázquez moves in the opposite direction: he extracts a single head from the frenzy and allows quiet to do the work. Where the North delights in inventory, the Spaniard delights in essence. The result feels modern because it reduces narrative and symbolism to make room for encounter. It also aligns with Velázquez’s broader practice in portraiture: minimal props, maximum presence.

Empathy Without Allegory

It is tempting to read the stag as an emblem—nobility, Christ, sacrifice—but Velázquez refuses to chain the image to a single meaning. His empathy is optical rather than allegorical. He does not ask the viewer to decode; he asks the viewer to look well. In doing so, he elevates the act of seeing to a moral exercise. The calm attention required to read the textures of nose, antler, and fur becomes a form of respect. That ethic threads through his portraits of people and reappears here as a way of meeting nonhuman life with dignity.

Anatomy and the Intelligence of Form

Everything in the head is anatomically persuasive, but persuasion arrives through design rather than diagram. The zygomatic arch gives the cheek its tensile curve; the masseter bulges with latent power; the shallow trough between nose and eyes produces the characteristic cervid profile. Yet no line announces itself as anatomy. Form is folded into the larger harmony of light and value. The intelligence is everywhere and nowhere on display, satisfying the knowledgeable viewer while seducing the casual one.

Cropping as a Modern Gesture

The decision to crop the antlers and eliminate the body brings the image close to modern photographic framing. It concentrates the drama at the plane of the face and invites the imagination to supply the rest. Cropping also denies the easy trophy narrative. This is not a wall mount; it is a head caught in motion. The closeness has an ethical charge: we are within the animal’s personal space, and the picture holds us there without aggression. It is an encounter calibrated for respect.

Sky, Cloud, and the Theology of Air

Velázquez’s sky is not a neutral curtain. Its broken clouds and gradations of blue model the dome of air that the stag inhabits. The cloud mass, crossing behind the muzzle and lower antlers, serves as a luminous counterform that pulls the head forward and keeps the silhouette crisp. That atmospheric care is more than craft. It situates the creature within creation, affirming the worldliness of the scene. The painting belongs to weather, not to studio allegory.

The Silence of Context

There are no hunters, no dogs in pursuit, no forest anecdote. The silence is eloquent. It refuses to tell us whether the animal is at peace or on alert, whether the next moment brings flight or stillness. That open narrative space turns the picture into a meditation on presence itself. In a court that used images to communicate rank and propaganda, this quiet may be the most radical choice. To look becomes the event.

Relationship to Velázquez’s Human Portraiture

Everything that makes the artist’s human portraits great—tonal economy, atmospheric unity, psychological tact—appears here translated into the language of another species. He finds character without caricature, structure without pedantry, and a balance between intimacy and distance that honors the subject’s dignity. Just as a royal sitter in black emerges as a person rather than a bundle of insignia, the stag here emerges as an individual rather than an emblem. The continuity across subjects testifies to Velázquez’s unwavering interest in the truth of appearances.

Material Presence and the Life of the Painting

The canvas carries the marks of making: underdrawing implied by confident placement, layers that thin toward the sky and thicken toward the highlights on nose and brow, edges softened by dry scumbling that fuse head with air. These material facts keep the painting alive under shifting light. As one moves before it, the muzzle gleams, the antler edges sharpen and relax, the eye deepens—subtle changes that feel like breathing. The object is not a fixed diagram; it is a durational experience.

Why the Image Endures

“Head of a Stag” endures because it reconciles opposites that are hard to keep together: simplicity and richness, immediacy and reflection, natural history and poetry. It invites specialists and lay viewers alike to linger, rewarding both with incremental revelations of craft and care. In an era that often asked paintings to demonstrate power, Velázquez demonstrates attention. That is why the image still feels fresh. It teaches us how to look at an animal with patience and respect, how to take pleasure in truth well seen.

Conclusion: Majesty Without Trumpets

Velázquez stands close, looks long, and paints little more than what is necessary. A head, a sky, a handful of strokes become a presence that holds its ground. The stag appears not as a trophy nor as a sermon, but as itself—alert, breathing, dignified in the daylight of its world. The painter, too, appears: not as a propagandist, not as a showman, but as a witness whose craft turns attention into art. In that exchange between animal and eye, “Head of a Stag” achieves a quiet majesty that needs no trumpets.