Image source: wikiart.org

A Young Master’s Study in Light and Character

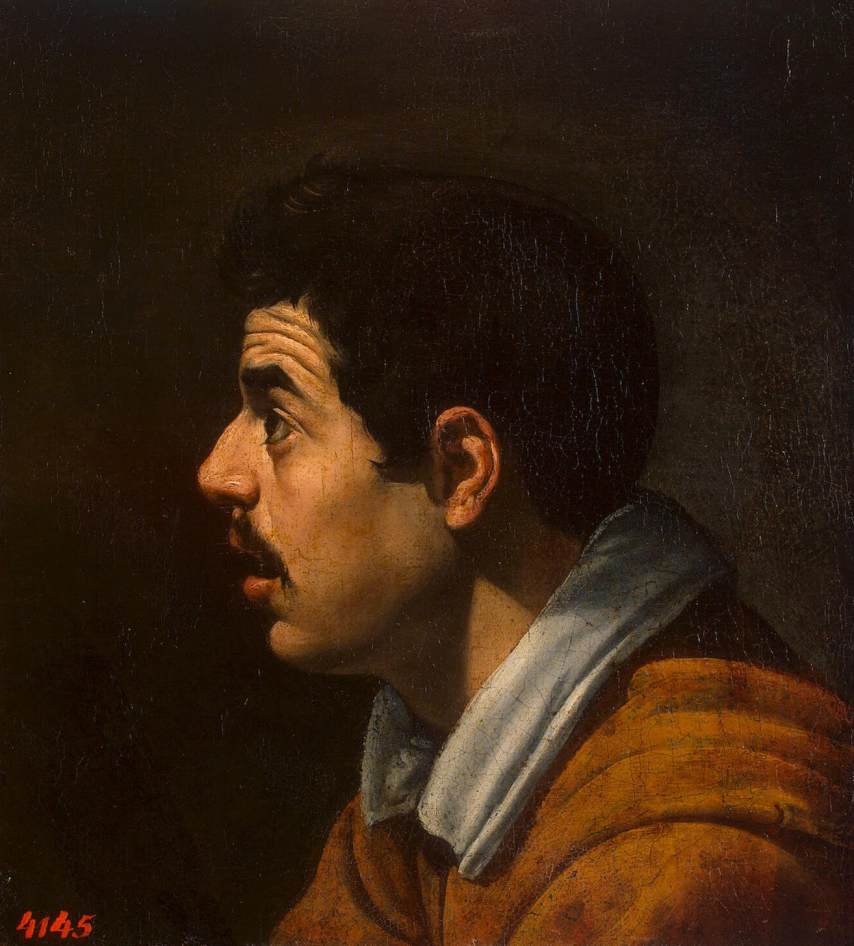

Diego Velázquez’s “Head of a Man” is a compact revelation from the earliest years of his career in Seville. Painted around 1616, when the artist was barely out of his teens, the work stages a single head in profile before a dark ground. The format is disarmingly simple: there is no narrative setting, no distracting ornament, and no emblem of status. Yet the canvas feels charged with thought. A raking light pours across the sitter’s face and collar, modeling bone, cartilage, and flesh with sculptural clarity while the surrounding darkness swallows everything unnecessary. The result reads at once as a technical exercise and as an independent picture, a fragment that contains a whole world of observation about how people look and how paint can make that looking matter.

Seville at the Beginning: Training and Ambition

To understand the picture’s quiet authority, it helps to place it in Velázquez’s formative context. He trained in Seville under his future father-in-law, Francisco Pacheco, whose studio emphasized drawing from life, learned iconography, and an upright moral tone. Velázquez absorbed those lessons but also pushed past them, turning toward a striking naturalism that sought truth in ordinary faces and the behavior of light. Seville in the second decade of the seventeenth century was a bustling, devout, and commercially active city; it had contact with Italianate trends and, through prints and travelers, with Caravaggio’s electrifying tenebrism. Young painters encountered a spectrum of influences—learned, local, and international—and Velázquez responded by making pictures that look like encounters with actual people rather than rehearsals of inherited types. “Head of a Man” belongs to that surge of early experiments in which he honed the craft that would make his later portraits and histories so piercing.

A Composition Condensed to Essentials

Everything in the painting serves the head. The figure is cut off at the shoulders, turned in full profile to the left, and set against a deep brown ground that reads as air rather than wall. The profile creates a crisp silhouette, a line of nose, lips, chin, and collar that the light sharpens and the shadow complicates. This “medal-like” view carries classical overtones while also serving as a pragmatic device: it makes the articulation of plane changes—forehead to temple, cheek to jaw—both visible and testable by the brush. The background is not merely blank; it is a carefully tuned darkness that supports the flesh tones without flattening them, allowing the head to project from the surface like a relief. If the goal was to train the hand and eye, the composition’s austerity is itself pedagogy: remove every distraction, then ask paint to do the rest.

Tenebrism and the Drama of a Single Light

A single, high light floods the face from the left, raking across the nose, cheekbone, upper lip, and the rim of the ear before dying into the warm gloom that encloses the back of the skull and the lower neck. This is tenebrism with a Sevillian accent. Unlike the brutal contrasts of some Caravaggesque followers, Velázquez moderates the jumps from brilliance to shadow with a surprisingly complex sequence of halftones. Warm ochres inch toward the highlight, cooler grays anchor the planes that turn away, and a faint reflected glow softens the jawline. The illumination is both descriptive and dramaturgic. It reveals the sitter’s physiognomy—his prominent nose, the fullness below the lower lip, the soft mustache—and it also assigns importance, inviting the viewer’s attention to the small topographies of bone and skin where character often seems to reside.

A Tronie, a Study, and an Independent Picture

Art historians often use the Dutch term tronie for a head study that is not a portrait of a specific person but an exercise in character, expression, or costume. “Head of a Man” shares much with that practice. The sitter’s identity is not recorded; the emphasis is on type and the public language of physiognomy rather than private biography. At the same time, the painting avoids caricature and exaggeration. It feels like a conversation with an individual, one whose features the painter respected even while he learned from them. The double nature of the work—as both exercise and picture—anticipates Velázquez’s lifelong ability to make studies that feel finished and finished works that preserve the freshness of study.

Flesh, Fabric, and the Tact of the Brush

Look long and the paint resolves into a choreography of minute decisions. The tip of the nose receives a tiny, high highlight; the nostril is shaped not by contour lines but by a warm red mingled with a cooler brown; the upper lip carries a delicate vertical glint that implies moisture; the ear is a miniature theater of half-lights and pockets of shadow that convey its convolutions without pedantry. The white collar, turned up beneath the chin, is painted with brisk, opaque strokes that catch the light and then collapse into a grayish hush as they turn to shadow. The garment—probably a coarse, warm brown—absorbs illumination quickly, reminding us that different materials return light in different ways. Velázquez is learning not only how to model a head but how to assign a distinct touch to each substance, a discipline he would later apply with legendary subtlety to silk, metal, and hair.

The Psychology of Profile

A head in profile can be impersonal, but here it feels alive and alert. The sitter’s mouth is parted slightly, suggesting he is mid-breath or about to speak. The eyebrow rises just enough to give the eye socket a sense of readiness. The profile’s sharpness is softened by the flexible edge where light loses to shadow along the cheek, an “edge of turning” that painters prize for its power to convey vitality. There is no grand narrative, yet the face seems to think. That quiet intelligence is the moral center of the picture and a clue to Velázquez’s later authority as a portraitist: he paints not an emblem of “a man” but the presence of a particular mind in a particular body.

Palette, Pigments, and Early Sevillian Practice

Early works by Velázquez typically favor earth colors—ochres, umbers, siennas—tempered by lead white and quickened with small amounts of vermilion or red lake for lip and ear. The background’s deep brown likely began as a thinly prepared ground, allowed to participate in the final effect so that the darkness is not a dull backdrop but a living atmosphere. The collar’s coolness may hint at a small addition of black or bone black to white, creating a soft gray that drops gently into shadow. Nothing is showy. The palette’s modesty is a virtue here, focusing attention on values and temperature relationships rather than on chromatic display, and the economy of means underscores the discipline of the exercise.

Anatomy, Measure, and the Sculptural Habit of Mind

Velázquez’s gift for modeling derives from more than keen sight; it reflects a sculptural habit of mind. In “Head of a Man” the planar structure of the face is palpable. The front plane of the forehead steps to the temple, the cheek swells and sinks, the zygomatic arch casts a short, telling shadow, and the jaw travels in a clean, angled descent. These are not academic demonstrations but felt truths. The painter is rotating the head in his imagination, testing how the light would fall if the sitter turned a few degrees, and capturing the result in measured transitions. That sculptural understanding later enables the great illusions of “Las Meninas,” where figures share air with the viewer; its embryonic form is already present here.

The Silence Around the Figure

Dark grounds in early seventeenth-century art can be brooding or bombastic. Velázquez’s is neither. It is a silence—the absence of architectural or narrative scaffolding that compels attention to the face. This silence is ethical as well as aesthetic. By refusing to distract, the picture offers a kind of respect to the sitter, who is neither flattered by rich surroundings nor diminished by anecdote. The head becomes sufficient, a microcosm worthy of a whole canvas, a stance that dignifies the common person and lays the foundation for the painter’s humane approach to royal sitters later in Madrid.

The Echo of Bodegón Practice

Velázquez’s earliest celebrated pictures in Seville were bodegones—kitchen and tavern scenes in which ordinary people and simple objects are staged under powerful light. Those canvases teach the eye to compare the different ways light behaves on pottery, cloth, glass, and flesh, and to orchestrate those differences into pictorial meaning. “Head of a Man” leverages the same training but compresses it. The collar and garment stand in for still-life materials; the head serves as both protagonist and most complex object; the dark field supplies the theatrical hush of an interior. Seen this way, the painting is a bodegón boiled down to essentials, with psychology replacing narrative incident.

From Workshop Exercise to Studio Tool

Works like this one likely served multiple functions in the studio. They were displays of skill for patrons, teaching aids for apprentices, and reservoirs of physiognomic types that could be adapted for larger compositions. The profile of a stalwart laborer, a soldier, or a shepherd could be summoned from memory once a painter had made such studies. Velázquez’s refusal to flatten the head into stereotype, however, means that even if it informed other pictures, it remains satisfying as a self-contained object. You are not looking at a prop; you are looking at a person encountered and recorded with unusual seriousness.

Brushwork You Can Sense but Not Count

Stand back and the head seems solid, even sculpted; step close and you discover how little paint and how few marks accomplish that solidity. Short, elastic strokes construct the modeling of the cheek; a thin scumble lightens the bridge of the nose; the mustache is a play of warm and dark notelets that congeal into hair only at a certain distance. Velázquez’s early touch is tighter than the later, famously “open” handling of Madrid, but the habit of suggestion is already present. The painter says just enough and no more, trusting the viewer’s eye to participate in completing the image.

A Young Man’s Confidence

Nothing about the picture feels tentative. The contour of the nose is decisive, the ear’s complicated edges are laid with clarity, and the sweep of the collar is established in a few confident planes. That assurance is remarkable for a painter so young. It suggests that by 1616 Velázquez had already absorbed Pacheco’s emphasis on drawing, filtered it through his own appetite for the seen world, and found a touch that could carry him from studies to public commissions. “Head of a Man” is a modest size but a major omen.

The Mystery of Identity and the Generosity of Not Knowing

Who is the sitter? A studio model, a friend, a worker, a passerby who agreed to hold still for a few days? The painting does not tell, and the omission is liberating. Without the scaffolding of biography, the viewer attends to universals of human presence—to the way breathing lifts the upper lip, to the energy that gathers in the brow when someone listens, to the texture of stubble along the jaw. The unknown identity becomes a gift, allowing countless viewers to recognize faces they have known and voices they can almost hear.

Comparisons That Clarify

Place this canvas beside other early heads in European painting and Velázquez’s difference comes into focus. Caravaggio and his Roman followers often turn the head into a mask lit by an interrogating lamp; northern tronies delight in costume and theatrical expression. Velázquez chooses neither path. His light is dramatic but not interrogatory; his expression is lively but not theatrical. The paint seems to have rested where the eye did, moving across forms with the patience of real looking. The result feels modern in the best sense: the painting respects the everyday, treats perception as a discipline, and trusts that specificity can carry meaning.

The Work’s Afterlife in a Career of Portraits

Later, in Madrid, Velázquez would paint kings and courtiers with a similar mixture of accuracy and mercy, allowing individuality to coexist with public role. “Head of a Man” is a seed of that achievement. The profile, the honest modeling, the refusal to decorate—these become the grammar from which he will write complex sentences in “The Surrender of Breda,” “Pope Innocent X,” and “Las Meninas.” When we look at this early head, we glimpse the moment when the grammar is first being learned, line by line, with enough mastery that even the exercise stands as a poem.

Why the Picture Still Feels New

Part of the painting’s freshness lies in its scale and directness. In an age of spectacle, a single head in a dark room can arrest attention precisely because it asks for nothing more than looking. The face is close enough to touch, the light believable, the brushwork transparent in its intentions. There is no mythology to decode, no emblem to chase. The picture’s honesty feels like a modern conversation held across four centuries: here is a person; here is how light shaped his features one day in Seville; here is paint placing those shapes on a small piece of linen; does this not still matter?

Conclusion: The Human Face as First Principle

“Head of a Man” is an early manifesto. It claims that the human face, carefully observed under truthful light, is sufficient to sustain a painting. The claim is humble and radical at once. From it, Velázquez will build a career that enthrones kings without flattering them and dignifies peasants without patronizing them. In this small canvas the essentials are already present: the sculptor’s sense of form, the dramatist’s command of light, the moralist’s respect for the ordinary, and the poet’s economy. The young painter has looked hard, painted exactly, and given us not a lesson disguised as art, but art that teaches by how simply and truly it sees.