Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

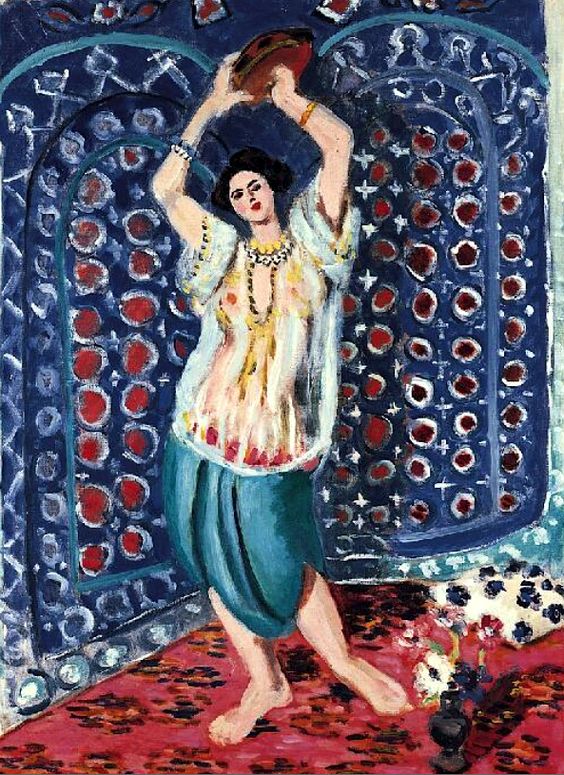

Henri Matisse’s “Harmony Tambourine in Blue” (1926) stages a kinetic conversation between figure, pattern, and color. A dancer lifts a tambourine above her head, her bare feet planted on a crimson carpet, while a monumental screen of patterned blue arches closes in behind her like a decorative proscenium. The scene is unmistakably of the Nice period: a shallow room turned into a theater of textiles and props, where the model’s movement is conducted by the intervals of ornament and the temperature of the palette. Nothing is incidental. The tambourine’s brown ellipse, the turquoise drapery at the hips, the white blouse’s feathered transparency, and the star-studded blue field collaborate to make rhythm visible. The result is a painting that feels at once exuberant and composed, with energy carried by color and held in check by a rigorous decorative order.

The Nice Period And The Turn From Shock To Harmony

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had transformed the audacity of his Fauvist years into a more measured classicism. He worked in rented rooms along the Riviera, gathering patterned screens, carpets, and studio props that could be arranged like musical instruments. The Nice interiors exchanged the clashing declarations of early modernism for tuned chords capable of sustaining long looking. “Harmony Tambourine in Blue” expresses that ethos explicitly. The word “harmony” in the title is not an ornament; it is the central aim. Movement, pattern, and color are made to agree without losing their individual strength.

Composition As A Stage Of Arches And Steps

The composition is organized as a shallow stage anchored by three major masses: the dark red carpet below, the towering blue screen behind, and the dancer’s pale blouse and turquoise trousers in the middle register. The screen is articulated as interlocking arches studded with small circular medallions and starry dots, a grid that simultaneously compresses space and sets a measured beat. The dancer leans slightly to the left, one knee bent and one leg extended, a counter-diagonal that prevents the screen’s symmetry from freezing the scene. The tambourine lifts the arc of the arms into the screen’s upper zone, creating a rhyme between human gesture and architectural curve. Because depth is minimal, the eye reads the scene as a tapestry of interlocking shapes, but the placement of bare feet, knees, and hips keeps the body convincingly grounded.

Pattern As Structural Rhythm

Pattern here is not backdrop; it is structure. The blue panels behind the dancer repeat arches at different scales, with white tracery that behaves like musical notation. The carpet’s spots and flower clusters form a slower rhythm in the lower half. The blouse’s vertical streaks of white, coral, and yellow flutter with the smaller fastest tempo, while the knotted trousers introduce wider bands of turquoise and shadow. Each pattern carries a tempo, and the dancer stands where these tempos meet, binding them with movement. This orchestration demonstrates Matisse’s belief that ornament can be the grammar of modern painting, a system of intervals that replaces traditional perspective as the chief organizer of space.

Color As Architecture And Temperature

Color does the work of architecture. The blue ground, ranging from indigo to ultramarine, is the dominant field; it cools the space and throws the warmer reds and skin tones forward. The carpet’s reds are tuned with broken brushwork into a vibrating surface that reads both as textile and as a platform of heat. The yellow necklace, bracelets, and blouse accents are small, bright notes that keep the chord lively, while the turquoise trousers connect blue to green, easing the jump from background to figure. The blouse is a miracle of pearly whites and faint corals that admit the body’s warmth without surrendering to it, so flesh reads through fabric as diffuse light. The tambourine’s brown echoes the carpet’s earthiness and stabilizes the upper zone of the painting. Nothing is pure; whites are milky, blacks are rare, and every color borrows a little from its neighbor so the surface breathes.

The Dancer As A Locus Of Energy

The model is neither allegory nor character out of folklore; she is a focus for the room’s energy. With arms raised and wrists flexed, she converts the screen’s arches into embodied motion. Her head tilts with a small countergesture that keeps the pose from stiffness, and her gaze is inward enough to suggest concentration but open enough to meet the viewer. The lowered blouse neckline and the transparent sleeves are not theatrical titillation; they are solutions to the pictorial problem of how to let the body’s warmth communicate through cool fabric. The bare feet, pink against the carpet, anchor the figure and mark the beat of the dance without a blur of motion. The result is a modern presence: poised, active, and at home in a decorative world.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

Matisse’s line builds the dancer with a series of exact, elastic boundaries. The arms are drawn with long, unbroken sweeps that thicken where muscles turn and thin across airy sleeves. The jaw is a single curve countered by the straight of the nose and a small, emphatic mouth. The trousers are shaped by gently alternating convex and concave lines that indicate gathered fabric without fussy description. Even the tambourine registers as a living ellipse whose slight irregularity confirms the handmade authority of the mark. These contours do not pin the figure down; they let color expand to volume while keeping the whole ensemble legible against the patterned field.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The painting is suffused with Mediterranean light, filtered as if through shutters and patterned screens. Shadows rarely sink into black. Instead, cool blues and violets provide relief along the inside of arms, under the blouse, and at the knees. Highlights are placed as creamy dabs on the tambourine’s rim, on jewelry, and along the blouse’s pleats, so the entire figure reads as illuminated from multiple soft sources rather than spotlighted. This diffused light allows color to carry modeling, fulfilling a Nice-period conviction that painting can be both luminous and calm without sacrificing form.

The Tambourine As Visual Metronome

The tambourine is a small but crucial device. It punctuates the upper edge of the canvas and gives the raised arms a destination, turning what could be a static stretch into an intentional act. Its warm brown is calibrated to echo the carpet while remaining distinct within the blue field. The circle itself is a counter to the screen’s repeating medallions, a larger, simpler disc that concentrates attention. In short, it is a metronome for the painting, measuring time and anchoring the phrase of movement that runs from hands to hips to feet.

The Carpet And The Grounding Of Heat

The red carpet is where the painting’s heat accumulates. Matisse scatters small motifs across it so that the color flickers rather than congeals, and he allows areas of deeper wine to pool in the corners to keep the center buoyant. The dancer’s feet sink into this field with small shadows that are chromatic rather than black, giving weight without killing color. The carpet’s warmth balances the blue screen’s vast coolness and keeps the vertical composition from sliding into chill monumentality.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Space remains shallow by design. The screen presses forward, the carpet tilts, and the dancer occupies a narrow middle lane. Despite this compression, the body feels solid because overlaps are clear: the blouse in front of the torso, the necklace over the blouse, the feet stepping over the carpet’s motifs. This balance between flatness and volume is the Nice period’s signature solution. It preserves the painting’s identity as a colored surface while permitting human presence to feel convincing.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

Matisse’s canvases often invite the eye to move at a particular tempo, and “Harmony Tambourine in Blue” proposes an allegro moderated by adagio rests. The view ascends the raised arms to the tambourine, descends through necklace and blouse pleats, crosses the cool trousers to the bent knee, touches the carpet’s warm notes, and loops back up along the screen’s arch. With each circuit, correspondences emerge: a white dot on the screen answering a blouse highlight, a turquoise shadow aligning with a panel seam, a yellow bead finding a cousin in the bracelet. The painting rewards prolonged looking because its rhythms are layered—fast in the blouse, medium in the screen, slow in the carpet.

Orientalism Reconsidered And Redirected

The subject belongs to a European history of Orientalist imagery—dancers, screens, carpets, and instruments deployed as signs of an imagined elsewhere. Matisse’s approach acknowledges and redirects that inheritance. He keeps the props but changes their function. They are no longer ethnographic markers but pictorial actors whose value lies in their colors, shapes, and rhythms. The dancer is not a fantasy type; she is a modern model participating in a rigorous studio construction. The painting thus turns a loaded genre into a field for formal investigation, where the decorative is a method rather than a mask.

Tactile Intelligence And Evidence Of Process

Close looking reveals the painter’s hand and the decisions that stabilize the harmony. The screen’s dots are dabbed with loaded paint that stands slightly proud of the surface; the blouse’s pleats are scumbled thinly so underlayers glimmer; the trousers are modeled by transparent greens laid over blue. Pentimenti—a shifted line along an arm, a darkened seam in the screen, a repainted flower cluster on the carpet—remain visible, giving the image time and honesty. The calm we feel is therefore earned; it is the product of adjustments that brought many forces into equilibrium.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Harmony Tambourine in Blue” speaks to Matisse’s contemporaneous odalisques and to earlier dance-related works. It shares with “Odalisque with a Tambourine” the circular instrument as counter-form, but here the figure is upright and the blue field dominates, pushing the color chord toward a cooler register. It echoes the decorative intensity of “Decorative Figure on an Ornamental Background” while substituting movement for repose. It also foreshadows the late cut-outs, in which figure and ground interlock as flat shapes of saturated color. Across these dialogues, the painting asserts Matisse’s consistent pursuit: a modern harmony achieved through the precise spacing of differences.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite the festive subject, the psychological tone is collected. The dancer’s face is simplified into concentrated planes; her eyes and mouth are marked with small, decisive accents that imply attention rather than abandon. The viewer experiences the scene as a sustained, lucid performance rather than a snapshot of frenzy. That lucidity is a hallmark of the Nice period. It invites the viewer to participate not by projecting narrative but by tracing relations—how a blue quiets a red, how a dot paces a line, how a lifted arm answers an arch.

Why The Painting Endures

This painting endures because its pleasures are structural and renewable. Each return uncovers a new hinge: a white fleck on the blouse that recruits a dot on the screen, a cool shadow along the ankle that balances the tambourine’s warm rim, a flower on the carpet that anchors a small star high in the panel. The image offers both immediate delight and slow-building consonance. The longer one looks, the more the title feels exact. The harmony is not a single effect; it is the felt result of many tuned relations, moving yet stable, bright yet dignified.

Conclusion

“Harmony Tambourine in Blue” condenses Matisse’s Nice-period convictions into an energized interior. The dancer animates a decorative stage, the tambourine marks time, the blue field breathes like night air, and the red carpet answers with warmth. Pattern is structure, color is architecture, and gesture is the bridge between them. Without appealing to narrative or spectacle, the painting achieves a poised intensity—a choreography of form that continues to pulse long after the first glance. It is an invitation to look as one listens to music: patiently, repeatedly, with the promise that harmony will keep offering more.