Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

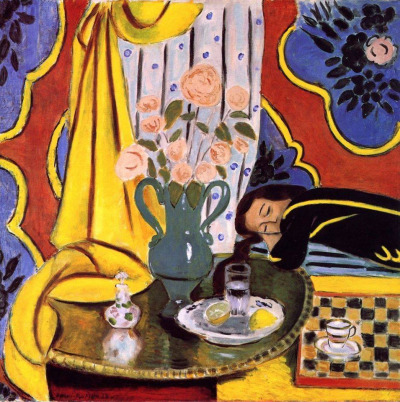

Henri Matisse’s “Harmony in Yellow” (1927) is a radiant chamber piece that condenses the painter’s Nice-period ideals into one densely orchestrated surface. A round table gleams like a bronze gong; a green jug brims with pale roses; a sleeping figure lies at the right edge, her black dress striped with calligraphic bands of yellow; a checkerboard drawer, a small perfume bottle, a glass of water, a spoon, and two lemon wedges complete the intimate ensemble. Everywhere the eye turns, yellow sets the key: curtains cascade in citrus folds, a table lip glints with metal warmth, and slim ribbons of cadmium outline forms across the painting. The background is a tapestry of red panels bordered in blue and black arabesques, so the whole picture feels like a theater of textiles and reflections. Matisse’s aim is not narrative. It is to demonstrate how color can be both structure and atmosphere, how pattern can regulate time, and how the human presence can anchor a room without breaking its calm.

The Nice Period And The Decorative Ideal

Painted during Matisse’s years on the Riviera, “Harmony in Yellow” exemplifies the shift from the explosive chords of Fauvism to a modern classicism based on tuned intervals. The Nice interiors are neither documentary nor sentimental. They are laboratories where color behaves like architecture and ornament becomes a principled grammar. In this canvas, the furniture is portable theater: a round table for reflections, a curtain that performs as a golden cascade, and a patterned wall that acts as a resonant backdrop. The model’s role is understated, almost private, so that the viewer attends to relations—hot color cooled by blue borders, repeating shapes translated across objects, and the steady pulse of pattern—rather than to story.

Composition As A Circular Score

The painting is organized from the circle outward. The round tabletop occupies the lower half of the canvas, tilting toward us to become a stage on which light plays. That circle governs the composition’s rhythm: the green jug’s belly repeats it; the glass adopts it in smaller scale; the saucer echoes it again; even the curled lemon peel glances at circularity. To the left, the curtain’s arc answers the table’s rim, and to the right, the sleeping head completes the circular motif with a human curve. The background is parceled into rhythmic compartments: a central red field with floral medallions, flanked by patterned blue-black shapes whose scalloped outlines tighten the surface. The table pulls us in; the panels steady our gaze; the figure arrests our movement so we stay long enough to hear the painting’s chord.

Yellow As Architecture, Light, And Temperature

Yellow is not a note but the atmosphere of the room. It drapes from the curtain like sunlight given cloth. It glows as a metal highlight along the table’s edge. It stripes the sleeper’s dress, runs through the checkerboard drawer, and infuses the roses with a warm undertone. Matisse uses different temperatures of yellow—lemon, straw, and honey—to model forms without relying on chiaroscuro. In the curtain, cool lemon strokes at the fold’s edges slide into warmer ochres where cloth thickens; on the table lip, a bright band sits on top of a deeper brass tone, so the metal seems both reflective and solid. Against the dominant red ground, yellow does not scream; it negotiates, borrowing a little warmth from the wall while receiving a cool counterweight from the blue borders that encase the patterns. The image becomes a study in how a single color can be medium, light source, and structural binder.

Pattern As Structural Rhythm

Pattern in “Harmony in Yellow” is not afterthought but meter. The background consists of repeating scalloped frames, each filled with floral clusters. Their blue outlines, edged with black, operate like musical bar lines, dividing the field into steady counts. The checkerboard drawer in the foreground answers that meter with its own grid—small squares alternating cream and brown, a miniature of order that keeps the lower right corner from dissolving into soft reflections. The sleeper’s dress translates the idea of pattern into linear calligraphy: two yellow bands curve along the sleeve and torso, echoing the scallops behind her while conforming to the body’s shifts. The result is an ensemble of tempos—slow in the large panels, quicker in the checkerboard, lyrical in the dress—held in one harmony.

The Round Table As Reflective Stage

Matisse relishes the round table’s capacity to register light. Its bronze top is brushed in long, circular pulls that catch highlights like spinning metal. Objects on its surface—jug, glass, saucer, perfume bottle—cast soft, colored reflections that mingle with the table’s own warmth. The lemon wedges sit as small suns, their pulp rendered with milky strokes that suggest translucency without fuss. The glass of water is a marvel of economy: a cylinder of faint grays and bright whites, it simultaneously reflects the curtain’s yellow and refracts the red panel, so it operates as a tiny theater of the room’s atmosphere. The table is therefore both a form and a mirror, gathering the painting’s chord into a single, resonant instrument.

The Sleeping Figure And The Poise Of Rest

At the right, the sleeper resolves the room’s energies into human calm. Her head lies on crossed arms; hair, brows, and lashes are simplified into dark arcs; the small mouth forms a soft accent that repeats the saucer’s pinkish rim. The dress is black not as emptiness but as a rich ground on which yellow lines gleam. That black also balances the deep blues around the floral frames, giving the composition a hinge at which warm and cool can meet. The figure’s posture is gentle, private, and untheatrical. She is present as a tempo—adagio—whose stillness lets the brighter objects play without agitation.

Drawing And The Breathing Contour

Line carries authority throughout the picture. The jug’s handles are drawn with quick, elastic curves that thicken where they join the body and taper at the lip. The curtain folds are set by long serpentine strokes that change pressure like a clarinet phrase. The scalloped background frames are hand-drawn rather than mechanical, so their edges breathe and keep the surface alive. The figure’s features are economical: a few sure marks place eyes, nose, and mouth; the jaw is a single curve with a small notch near the ear; the sleeve line breaks and resumes where fabric turns. These living contours contain color without stiffening it, allowing paint to feel both graphic and luminous.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The canvas is saturated with soft, reflected light—the Mediterranean at noon filtered through shutters and curtains. There is almost no black shadow; darkness is reserved for pattern, hair, and a few emphatic outlines. Modeling is achieved chromatically. The jug grows by shifts from green to blue-green; the curtain turns by cooling its yellows; the table rounds by mixing ochre into bronze and then skimming on pale highlights. The result is light that does not point from a single source but seems to arise from the painted color itself. This is the Nice period’s hallmark: luminosity produced by relations rather than by theatrical contrast.

The Dialogue Of Objects: Jug, Glass, Lemons, And Perfume

Each still-life element is tuned to the whole. The jug’s green opposes the curtain’s yellow and recruits the foliage of the roses, knitting bouquet to vessel. The water glass and saucer offer cool whites that echo the sleeper’s skin and pearls, linking human presence to object world. The lemons are the painting’s inner suns—small orbs of energy that echo the curtain’s cascade and the yellow bands on the dress, yet they are tempered by greenish shadows so they sit in space. The tiny perfume bottle at left gleams with a dot of highlight and a faint wash of pink; it is a miniature of the painting’s thesis: a bright accent modulated by relation, not shouted into isolation.

Roses As Measured Lyrical Notes

The bouquet’s roses are painted with light, quick strokes that refuse botanical description and instead state temperature and value: cool pinks laced with cream for petals, blue-green for leaves, gray-violet for shadowed whorls. Their stems disappear into the jug, and a few heads rise just high enough to converse with the curtain’s upper fold. The bouquet’s scale is crucial—large enough to command the table but not so large as to challenge the figure. It mediates between human and object, organic and crafted, soft and solid, and it quietly repeats the circle motif while adding a fluttering counter-rhythm.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Matisse compresses space deliberately. The wall presses forward as patterned fabric; the curtain occupies the picture plane like a hanging tapestry; the table tilts up to present its objects plainly. Overlaps and reflections provide just enough depth to be convincing: the saucer eclipses the lemon; the jug stands in front of the curtain; the glass sits before the bouquet; the checkerboard drawer slides under the sleeper’s elbow and into our space. This productive flatness keeps attention on the surface, where color and pattern meet to form the painting’s true architecture.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

“Harmony in Yellow” is composed for the eye the way chamber music is scored for the ear. The scalloped backgrounds beat a steady measure; the curtain’s folds provide a supple melody; the table and its objects play a set of clear, bright motifs; the sleeper holds a sustained low note. The viewer follows a route: from the curtain’s knot down the yellow cascade to the jug, across the glass to the lemons, over the checkerboard to the resting head, and back up the black-and-yellow sleeve to the bouquet. Each circuit reveals a new correspondence—a lemon wedge rhyming with a rose’s creamy center, a yellow stripe on the dress answering the table’s glint, a blue outline in the border repeating along a petal’s shadow. The painting insists that harmony is not a single effect but a continuum of tuned relations.

The Ethics Of Ornament And The Modern Interior

The Nice interiors have sometimes been dismissed as merely decorative, yet their discipline is exacting. Ornament here does not drown the figure; it shares the stage. The person is honored by the same care given to curtain, plate, and stripe. The so-called “exotic” elements—scalloped frames, arabesques, checkerboard—are not souvenirs; they are functional devices for spacing, pacing, and clarifying the surface. In this sense the painting modernizes domestic pleasure. It proposes that a room can be a site of rigorous thought, and that a restful scene can be the product of exact decisions.

Tactile Intelligence And The Reality Of Paint

Close looking reveals the canvass’s tactile intelligence. The table’s bright edge is laid with a thicker, enamel-like stroke; the curtain’s yellows are scumbled thinly so the weave participates; the jug’s body is built with broader, creamy paint that suggests glazed ceramic; the black dress absorbs light in velvety passages; the checkerboard is briskly blocked so its edges feather just enough to stay human. Small pentimenti whisper through: a shifted petal, a nudge to a border, a reinforced table rim. These traces are not mistakes but memory—evidence that harmony is earned by revision.

Comparisons Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

This canvas speaks to Matisse’s “Harmony in Red” from years earlier, but reverses the key: here yellow, not red, acts as the primary climate, with red now serving as supporting field. It converses with Nice-period odalisques by trading the reclining figure’s dominance for a still-life-centered stage; the human presence remains, but as a quiet partner. It also anticipates the serene economies of the late cut-outs: bold shapes edged with emphatic color, figure and ground nearly equal in power, harmony derived from spacing rather than modeling.

Psychological Tone And Viewer Experience

Despite saturated pigment and crowded pattern, the psychological tone is calm, almost drowsy. The sleeping figure sets the mood; the roses, glass, and lemons are careful companions rather than lively actors; the curtain hangs like a suspended phrase. For the viewer, the experience is hospitable. One can linger in the painting without fatigue, because every area offers a small adjustment of temperature, a measured change of edge, or a tidy reflection that rewards attention. The harmony is not sugary; it is thoughtful. It slows the pulse without dulling the senses.

Why The Painting Endures

The work endures because its pleasures are structural and therefore renewable. On a first viewing, yellow’s radiance charms. On subsequent viewings, one begins to trace the stitching: the way a lemon’s highlight recruits the table’s glint; how a blue outline at the border is echoed in the jug’s cool shadow; how the pink of a saucer finds a twin in a rose’s heart; how the black dress locks the composition’s cooler register to the red ground. None of these correspondences exhausts the image; they keep opening avenues for attention. The painting supports daily looking—the ultimate test of decorative art with intellectual ambition.

Conclusion

“Harmony in Yellow” is a manifesto for the Nice period’s central belief: that color and pattern, handled with intelligence, can house human feeling without fanfare. Matisse builds a room in which yellow behaves as light and architecture, objects perform as notes in a measured score, and a resting figure confers time. The composition is circular yet open, saturated yet airy, intimate yet formally strict. It proves that harmony is not bland agreement but the lively spacing of differences—yellow with red, circle with panel, reflection with cloth, sleep with flowers—that together make a durable calm. Stand before the work and you feel how attention settles, how the eye’s breath slows, and how the room’s warmth feels earned rather than easy.