Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

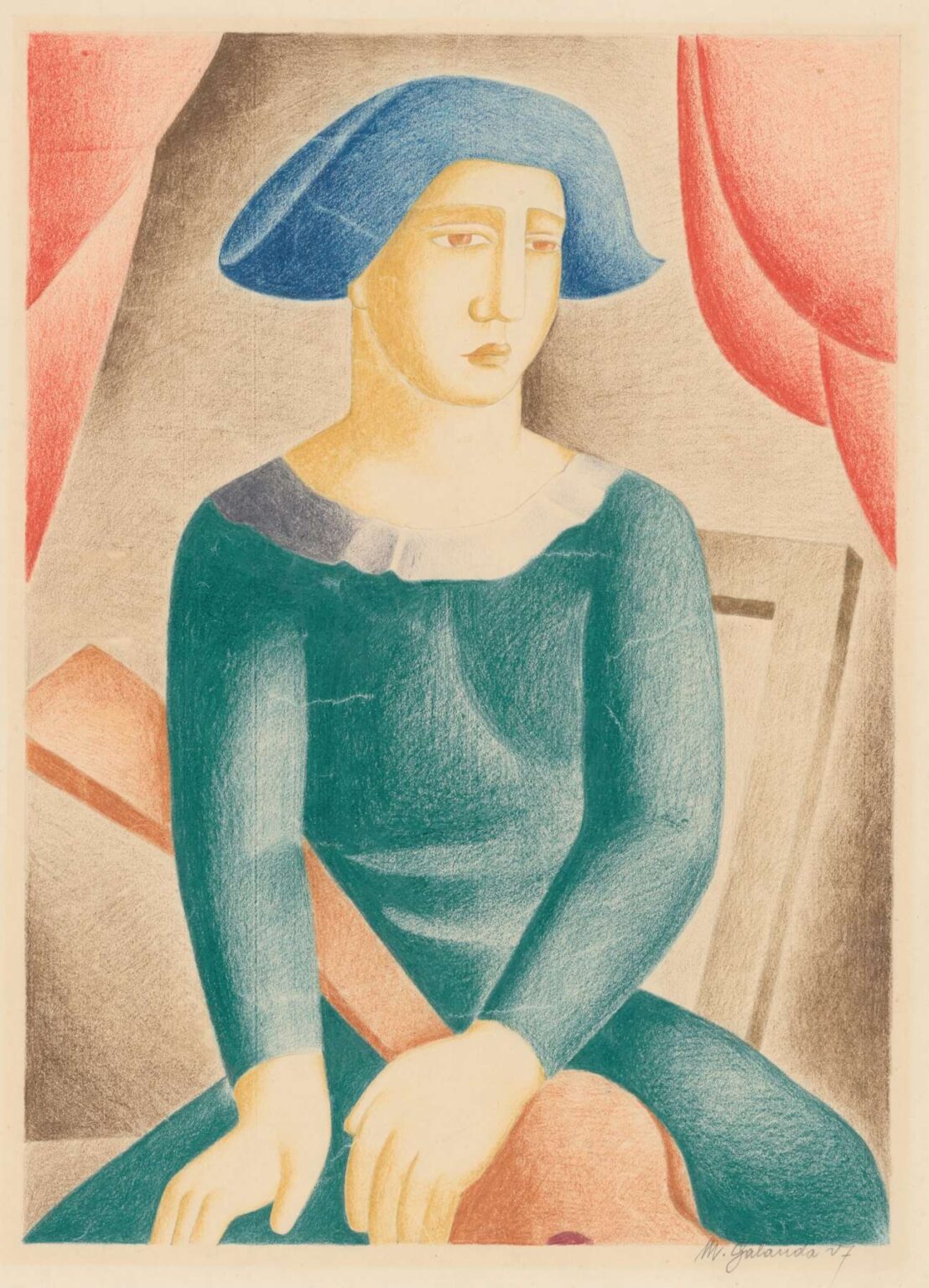

Mikuláš Galanda’s Harlequin (1927) is a striking example of interwar Slovak modernism, presenting an iconic theatrical figure through a synthesis of simplified form, evocative color, and subtle psychological insight. At first glance, the viewer is drawn to the unmistakable costume of the Harlequin—bold geometric shapes and contrasting hues—that seem to burst forth from the paper. Yet beneath the decorative surface lies a sensitive portrayal of the figure’s inner life, captured through delicate modeling of the face and thoughtful arrangement of pose. This analysis will explore how Galanda transforms a commedia dell’arte archetype into a modern emblem, tracing the work’s historical roots, formal strategies, symbolic resonances, and enduring significance in both his own career and the broader trajectory of Central European art.

Historical Context

The year 1927 stood at the crossroads of optimism and upheaval in Czechoslovakia. Less than a decade had passed since the formation of the republic, and artists sought to express the newfound national identity while remaining in dialogue with avant‑garde currents emanating from Paris, Munich, and Vienna. Theater and performance held a special allure for modernists, serving as laboratories of experiment in costume, gesture, and set design. Galanda, then in his early thirties, had already immersed himself in debates on art’s social function and the blending of folk tradition with modernist aesthetics. By selecting the Harlequin—a character rooted in Italian commedia dell’arte—Galanda nods to the performative spirit of the age, while simultaneously appropriating an international motif to articulate his vision of Slovak cultural renewal.

Mikuláš Galanda’s Artistic Background

Born in 1895 in Rimanovce, Galanda trained at the Hungarian Royal Academy in Budapest, absorbing academic disciplines before venturing to Munich and Vienna, where he encountered Secessionism and Expressionism. His early career encompassed richly colored figurative paintings and folk‑inspired woodcuts, but by the mid‑1920s he had gravitated toward graphic media—lithography, pen‑and‑ink drawing, and pastel—seeking precision of line and economy of means. In 1928 he co‑founded the Nová Trasa (New Path) group, advocating for an art that was both modern and accessible. Harlequin emerges just prior to this milestone, showcasing Galanda’s mature graphic style: the bold outline, the controlled palette, and the interplay of flat shapes and subtle modeling that would become hallmarks of his subsequent work.

Formal Composition and Design

At the core of Harlequin lies a masterful orchestration of geometric and organic forms. The figure occupies the central plane, flanked by a muted background that neither competes nor recedes too far. The costume’s diamond pattern—rendered in alternating fields of color—establishes a rhythmic visual cadence. Galanda arranges the Harlequin’s right arm across the waist, creating a diagonal counterpoint to the vertical body axis. This interplay of diagonals and verticals lends the composition both stability and dynamism. Negative space around the figure’s head and shoulders allows the silhouette to resonate against the paper, while the head’s slight tilt introduces a gentle curve that softens the overall geometry. Through these compositional choices, Galanda ensures that the viewer’s gaze travels fluidly across the costume’s patterns, down the limbs, and back to the thoughtful expression on the face.

Line Quality and Contour

Line serves as the foundational element in Harlequin. Galanda applies confident, unbroken contours to define the figure’s silhouette and costume edges. Within these outlines, thinner, more gestural lines articulate facial features—the delicate curve of the eyebrow, the gentle slope of the nose, the subtle parting of the lips. The juxtaposition of thick and thin strokes enlivens the drawing, preventing it from appearing static. In sections of the costume, limited hatch‑like marks indicate slight folds and suggest the body’s underlying form without resorting to extensive shading. Galanda’s mastery of line is evident in its dual capacity: to convey bold, graphic impact and to capture nuanced human expression with minimal means.

Use of Color and Tonal Balance

While primarily a work of drawing, Harlequin incorporates a restrained yet expressive palette—typically red, blue, yellow, and black—applied in pastel or watercolor washes. Each color occupies its own field, corresponding to the classic Harlequin costume pattern, yet Galanda modulates intensity to achieve a cohesive tonal balance. The red areas possess a warm vibrancy that animates the composition, while the cooler blues and muted yellows provide counterweight. Black serves both as outline and accent, anchoring the lighter hues and lending depth to the folds of fabric. The figure’s face, rendered in soft beige or light gray, emerges from these surrounding colors, drawing attention to the psychological dimension of the portrait. Through careful color distribution, Galanda avoids overloading any quadrant of the drawing, ensuring visual harmony.

Modeling and Three‑Dimensional Suggestion

Despite the overall flatness of the costume’s pattern, Galanda introduces subtle modeling that suggests the Harlequin’s corporeal form. Soft tonal gradations around the cheekbones and under the chin convey the curvature of the head, while gentle shading on the hands reveals knuckles and finger joints. These localized zones of volume work in concert with the bold, flat color fields to create a figure that feels both emblematic and embodied. Galanda’s approach reflects the Modernist tension between surface design and illusionistic depth: he offers enough volume cues to humanize the character without undermining the decorative purity of the composition.

Psychological Expression and Mood

Unlike many mask‑like Harlequin depictions, Galanda’s figure possesses a contemplative, almost melancholic gaze. The eyes, half‑closed and directed slightly downward, suggest introspection rather than theatrical flamboyance. The mouth, set in a neutral line, conveys neither overt joy nor sorrow but hints at internal complexity. This reserved expression contrasts with the vibrant costume, creating a poignant dissonance: the performer’s outer guise does not fully reveal the inner temperament. The viewer is invited to ponder the person behind the mask, to sense the contradictions between role and self. In this way, Galanda elevates the Harlequin from a mere stage cliché to a universal figure of human duality.

Symbolism of the Harlequin

The Harlequin has long symbolized wit, agility, and the subversion of social order, originating in sixteenth‑century Italian commedia dell’arte. In Galanda’s hands, the character becomes a vessel for exploring themes of identity, performance, and cultural hybridity. The diamond‑patterned costume, originally a utilitarian patchwork, transforms into a modernist canvas—an artistic statement about fragmentation and synthesis. Positioned in Czechoslovakia’s interwar milieu, the Harlequin may also reflect the nation’s pursuit of unity amid diversity: different colors and shapes coalesce into a harmonious whole. Furthermore, the Harlequin’s traditional role as a trickster resonates with avant‑garde strategies of unsettling conventions, a role Galanda likely identified with as he navigated the shifting landscapes of Slovak and European art.

Costume and Cultural Reference

Galanda’s attention to costume detail underscores his engagement with theatrical and folk traditions. The Harlequin’s hat—often depicted as a floppy cap with a dangling tail—is here rendered with stylized simplicity, its form echoing the curves of the face. The diagonal sash across the torso reinforces the commedia dell’arte motif while serving as a compositional element, guiding the eye from shoulder to hip. Though the costume’s pattern aligns with centuries‑old imagery, the execution—clean planes, crisp edges, and controlled color application—feels distinctly modern. This fusion exemplifies Galanda’s broader cultural project: to honor vernacular heritage while advancing a progressive visual vocabulary suited to contemporary audiences.

Relation to Slovak Modernism

Harlequin holds a special place in Slovak modernism, exemplifying the ambitions of artists who sought to forge a national art that conversed with European avant‑garde movements. Galanda and his peers in Nová Trasa embraced techniques of Cubism, Fauvism, and Expressionism, yet always filtered these influences through local sensibilities. The Harlequin, as an international theatrical figure, becomes a bridge between global and regional narratives. Its graphic clarity and restrained palette provided an alternative to academic realism, offering a blueprint for future generations of Slovak graphic designers, illustrators, and fine artists to integrate folk motifs within modern frameworks.

Technical Mastery and Media

Galanda’s choice of media—likely a combination of pen‑and‑ink, pastel, and watercolor—demonstrates his versatility and command of mixed techniques. The pen provides crisp contours, pastels yield vibrant color fields, and watercolor washes offer subtle tonal variations. The seamless integration indicates careful layering and an understanding of each medium’s drying behavior and textural qualities. The paper’s warm tone contributes to the overall harmony, responding to both cool blues and warm reds. This technical dexterity underscores Galanda’s belief in drawing as a primary art form, capable of conveying as much nuance as oil painting.

Legacy and Influence

Nearly a century after its creation, Harlequin remains a landmark in the history of Slovak graphic art. It is frequently included in retrospectives of Central European interwar drawings and prints, praised for its elegant synthesis of folk and avant‑garde elements. Graphic designers and illustrators cite the work as an early example of how pure line and limited color can achieve profound visual impact. Art historians note its significance in shaping a modern Slovak aesthetic that balanced national identity with international discourse. The Harlequin has also inspired contemporary artists exploring themes of performance, identity, and cultural hybridity, ensuring Galanda’s inventive spirit endures.

Conclusion

Mikuláš Galanda’s Harlequin (1927) stands as a testament to the power of graphic reduction and symbolic depth. Through the interplay of bold costume patterns, nuanced modeling of the face, and a restrained yet expressive palette, Galanda transforms a theatrical stock character into a universal emblem of human complexity. The drawing’s seamless fusion of folk tradition and modernist form exemplifies the ambitions of Slovak artists in the interwar period to craft a visual language that was both locally rooted and internationally engaged. Decades later, Harlequin continues to captivate viewers with its blend of decorative allure and introspective resonance, confirming its status as a masterpiece of Central European modernism.