Image source: artvee.com

Introduction

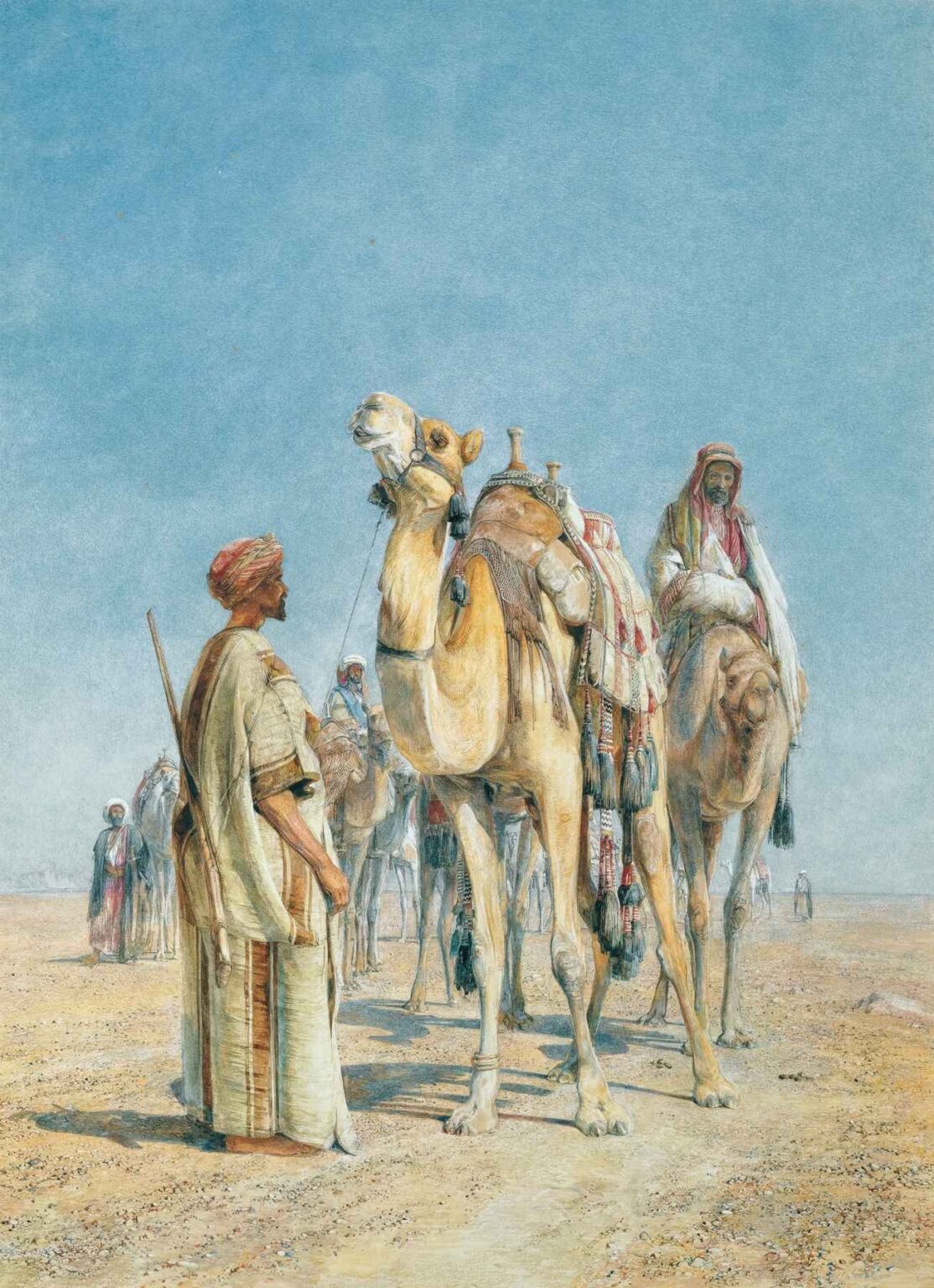

John Frederick Lewis’s “Halt in the Desert” (c. 1871) represents the zenith of 19th-century Orientalist painting in Britain. Executed in meticulous watercolor on paper, the work portrays a caravan of Arab travelers pausing amid a vast, sandy expanse. At first glance, the scene captivates with its glowing luminosity and ethnographic precision; on closer inspection, one discovers a layered meditation on cultural encounter, the poetry of light, and the artist’s nuanced negotiation between documentary realism and Romantic imagination. This analysis examines the painting’s historical and artistic context, Lewis’s personal journey and technique, the composition’s structural harmony, the coloristic effects and play of light and shadow, the ethnographic and symbolic dimensions, and the work’s reception and legacy. Through these lenses, “Halt in the Desert” emerges not only as a masterwork of watercolor but also as a complex artifact of Victorian attitudes toward the Orient.

Historical and Artistic Context

By the mid-19th century, European fascination with the Middle East had reached fever pitch. Archaeological excavations in Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia combined with increased travel facilitated by expanding steamship lines and railways. Intellectual currents such as Romanticism prized the exotic “Other,” and artists from Eugène Delacroix to David Roberts journeyed eastward, producing visual accounts that both documented and idealized foreign lands. In Britain, the Grand Tour tradition extended beyond classical Italy to include Ottoman provinces, North Africa, and the Levant. John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876) distinguished himself among these travelers by settling for long periods in Cairo and Damascus, embedding himself in local customs rather than merely sketching from afar. His watercolors epitomize the meticulous detail of topographical art while suffusing scenes with a tempered lyricism that avoids sensationalism. “Halt in the Desert” thus belongs to a mature phase of Orientalism, one in which the artist’s firsthand experience and personal relationships underpin a more empathetic representation of Arab life.

The Artist: John Frederick Lewis

Born into a London family of artists in 1804, Lewis trained at the Royal Academy and exhibited his first works there in 1822. Early career disappointments in oil painting prompted a pivot toward watercolor, in which he achieved technical mastery. A transformative six-year sojourn in Morocco (1841–1846) acquainted him with Islamic architecture and daily life; this was followed by further travels to Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. Unlike many contemporaries who swiftly returned home, Lewis remained in Damascus from 1851 to 1858, marrying an Egyptian woman and adopting local dress. His immersion manifested in works celebrated for their ethnographic accuracy—costumes, camel harnesses, architectural details rendered with forensic precision. Yet Lewis’s watercolors transcend mere documentation: his compositions exhibit careful balance, and his luminous washes evoke desert heat and sky-borne light. By the time he painted “Halt in the Desert”, Lewis had become the preeminent British Orientalist, admired for combining scholarly observation with refined aesthetic sensibility.

Provenance and Patronage

Although exact commission records for “Halt in the Desert” are scarce, the painting was likely executed for an affluent European collector fascinated by Oriental scenes. Watercolors of this scale and quality fetched considerable sums in mid-Victorian London exhibitions. After Lewis’s death in 1876, many of his works entered private collections; in the early 20th century, “Halt in the Desert” passed into a major museum’s holdings, where it has remained a highlight of watercolor galleries. Its provenance underscores the high esteem in which Lewis was held by contemporary British patrons, who valued both his rare technical prowess and the exotic allure of his subject matter.

Composition and Spatial Structure

Lewis constructs “Halt in the Desert” around a subtly radiating composition that mirrors the sunlit flatness of the desert landscape. The central camel, seen head-on, dominates the foreground and establishes a vertical axis. To its left and right, figures and mounts recede in shallow diagonal planes, creating a sense of measured progression rather than dramatic depth. The horizon line sits high, yielding a vast expanse of sand below and pale sky above; this split emphasizes the desert’s monolithic horizontality. Yet Lewis avoids monotony through subtle tonal shifts in the dunes, the patterning of camel blankets, and the rhythmic placement of travelers. The principal group clusters at center, their stillness accentuated by two solitary figures farther back, whose miniature scale reinforces the caravan’s isolation. Overall, the spatial arrangement conveys both the immensity of the desert and the communal intimacy of the travelers’ brief pause.

Color Palette and Treatment of Light

One of Lewis’s greatest achievements in “Halt in the Desert” is his handling of color to evoke desert conditions. The sand is rendered in a spectrum ranging from pale ivory to warm ochre and muted sienna, applied in washes that capture both glare and subtle shadow. Camel hair, leather harnesses, and flowing garments introduce earth-toned accents—burnt umber, raw sienna, olive green—while occasional dabs of crimson tassels and cerulean turban cloth create focal points. Above, the sky shifts from near-white at the horizon to a cool, almost silvery blue overhead, suggesting the desert midday sun’s bleaching effect. Light in Lewis’s watercolor is ambient rather than directional; no hard cast shadows appear, reinforcing the diffused brilliance of open desert air. The result is a luminous surface that shimmers with heat and air, enveloping figures in the desert’s timeless glow.

Depiction of Figures and Ethnographic Detail

Lewis’s years in Damascus endowed him with an unparalleled familiarity with Arab dress, accoutrements, and mannerisms. In “Halt in the Desert”, each rider and attendant wears distinct headgear—red fez, white keffiyeh, striped turban—painted with delicate brushwork that suggests fold and texture. The camels’ harnesses and saddles, laden with rolled carpets, water skins, and wooden chests, are rendered with exacting precision: leather straps show minute stitching; brass decorations glint in a single highlight. Lewis positions his figures in natural, unposed attitudes—some conversing in hushed tones, one man squatting to pour water, another leaning on a spear—conveying the spontaneity of a genuine camp halt. This attention to vernacular detail transforms the painting into both an art object and an anthropological record of mid-19th-century desert life.

Landscape and Setting as Character

In Lewis’s vision, the desert itself becomes a character: an unrelenting companion to the caravan’s passage. The dunes, though devoid of vegetation, display ripples and tracks that animate the surface. Scattered pebbles and sparse stones hint at the landscape’s geological reality. The distant horizon remains featureless, save for a faint dust haze that merges sand and sky. This austere environment both subsumes and elevates the travelers; their vibrant attire and the camels’ height break the monotony, yet they seem infinitely small against the desert’s breadth. The setting underscores themes of endurance, transience, and the nomadic ethic—man and beast perpetually moving through a world at once empty and sublime.

Technique and Brushwork

Watercolor demands confidence and control; once a wash is laid, it cannot be erased. Lewis’s technique in “Halt in the Desert” combines broad, transparent washes for the sand and sky with tighter, more opaque touches for details. He often built color gradually: a pale wash of yellow ochre followed by layers of burnt sienna to model dune forms, then a gentle application of gum arabic to heighten sheen. For the figures and camels, he used fine sable brushes to articulate harness buckles, facial features, and garment embroidery. His mastery of wet-in-wet blending produces seamless tonal gradations, while drybrush stippling adds texture to animal fur and rocky ground. This virtuosity in watercolor not only conveys material specificity but also demonstrates Lewis’s belief in the medium’s capability for grandeur.

Iconography and Symbolism

Beneath the painting’s surface realism lies a quiet symbolic resonance. Caravans historically symbolize human perseverance, cultural exchange, and the bridging of distant realms. The moment of halt suggests a pause in life’s journey—a time for rest, reflection, and communal bonding. Water, though invisible here, is ever-present in the loaded skins, underscoring the preciousness of sustenance. The camels, known as “ships of the desert,” embody endurance and adaptability. By juxtaposing sturdy beasts with ephemeral dunes, Lewis evokes the tension between permanence and impermanence—the civilization of human migration against the blank slate of desert. In this sense, “Halt in the Desert” can be read as an allegory for life’s journey through uncharted expanse, marked by fleeting respites and shared solidarity.

Orientalist Context and Reception

While modern critics have questioned Orientalist tropes, Lewis’s work enjoys a more measured appraisal due to his immersive practice. His depictions avoid overt eroticization or moralizing; instead, they emphasize dignity and everyday humanity. Victorian viewers celebrated “Halt in the Desert” for its novelty and “authentic” portrayal of foreign lands. Contemporary scholars note that Lewis negotiated the politics of representation by collaborating with local sitters and adopting certain customs, though he still maintained a European vantage point. Today, the painting is acknowledged as a product of its time—both a valuable ethnographic document and a testament to the asymmetries inherent in cross-cultural gaze.

Comparative Perspectives

In contrast to the dramatic oil panoramas of David Roberts’s Holy Land vistas, Lewis’s desert scenes are intimate watercolor studies that foreground human detail over monumental architecture. Compared to Delacroix’s expressive brushwork and vivid color in Orientalist subjects, Lewis offers restraint and precision. His approach aligns more closely with his contemporary Edward Lear, whose travel sketches also combined accuracy with personal reflection. However, Lewis surpasses many peers in technical command of watercolor, elevating the medium from sketchbook note to finished masterpiece worthy of museum display.

Emotional Resonance and Viewer Engagement

Despite its documentary fidelity, “Halt in the Desert” resonates emotionally. The viewer senses the travelers’ physical fatigue, the oppressive heat, and the calm solidarity that arises in shared hardship. The painting’s stillness invites the observer to linger, to study each fold of cloth, each grain of sand, and to imagine the caravan’s next steps. This empathetic engagement bridges cultural distance: one need not have crossed a desert to feel kinship with those who have. Lewis’s balanced composition and luminous washes create a contemplative mood, allowing the painting to function as both a window into a foreign world and a mirror reflecting universal themes of journeying and community.

Legacy and Influence

John Frederick Lewis’s mastery of Orientalist watercolor influenced generations of British and European artists who saw in his work a model for combining scholarly observation with aesthetic refinement. His desert scenes inspired later painters and illustrators working in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia. In museum collections, “Halt in the Desert” remains a standout example of watercolor’s potential for grandeur—demonstrating that the medium can rival oil in scope, detail, and emotional depth. Recent exhibitions on Orientalism have re-examined Lewis’s oeuvre, highlighting both its technical brilliance and its complex role in 19th-century representations of “the other.”

Conclusion

Through “Halt in the Desert,” John Frederick Lewis achieves a remarkable synthesis of precision and poetry. His watercolor captures the stark beauty of a desert caravan pause while offering deeper reflections on human endurance, cultural encounter, and the interplay of permanence and transience. From the exactitude of ethnographic detail to the radiance of luminous washes, every aspect of the painting testifies to Lewis’s unparalleled skill and immersive vision. More than a historical document, “Halt in the Desert” invites contemporary viewers into a timeless journey—reminding us that art, at its best, can transport us across sands, cultures, and centuries in a single, enduring image.