Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

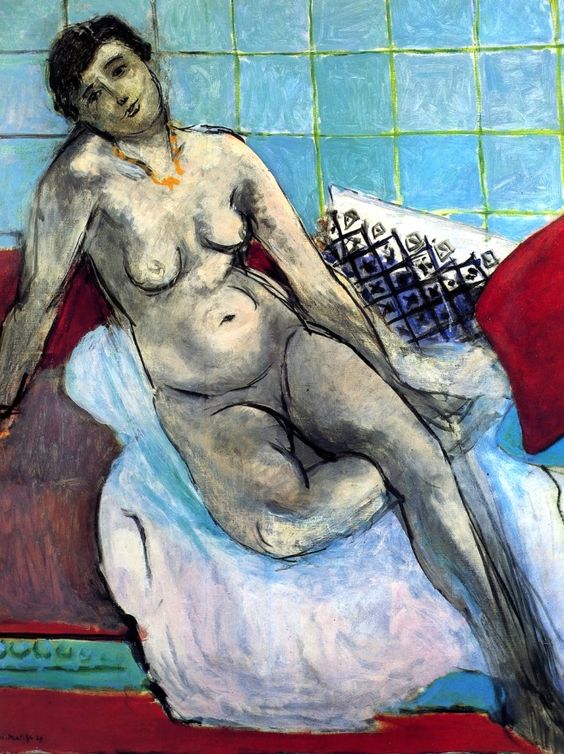

Henri Matisse’s “Grey Nude” (1929) is a remarkably candid summation of the late Nice period: a reclining figure rendered almost entirely in a cool, pearlescent register, set against a room built from turquoise tiles, white bedding, and jolts of red. The painting strips the odalisque theme of exotic ornament and lets structure, contour, and temperature carry the experience. The model leans diagonally across a low couch, her torso upright but relaxed, head tipped toward the viewer, one knee raised, one leg tapering away. A necklace, a patterned pillow, and two crimson cushions provide sparing accents. Everything else is a conversation between gray flesh and a sea-cool interior. The canvas argues that restraint can be opulent when color is tuned and drawing breathes.

Composition As Diagonal Theatre

Matisse organizes the scene with a commanding diagonal that runs from the model’s right shoulder to the extended left leg. This slant activates the rectangle, preventing the stable horizontal of a typical odalisque from turning static. The triangular wedge of bedding at lower right counters the body’s diagonal and locks the figure into place. A narrow strip of floor at the bottom—a band of red broken by turquoise moulding—acts as a stage apron, a final brace that keeps the eye within the frame. The head is set near the upper left third, where the grid of wall tiles and the line of the shoulder meet; this hinge concentrates attention without resorting to spotlight theatrics. Each part is a deliberate fulcrum: the elbow pressing into the cushion, the knee projecting toward us, the foot dissolving into the bedding. The result is a poised arrangement that feels spontaneous because all the pressures are well caught.

Color As Climate And Architecture

The title’s “grey” is a living climate rather than a single color. Flesh is built from layered, semi-opaque mixtures of blue, violet, and warm stone, then tempered with quick accents of warm peach where blood rises. These nuanced neutrals read as skin not through descriptive detail but through temperature shifts: cool pools in the hollows of the ribcage and thigh, warmer lights along stomach and breast, a faint violet drift across the shadowed side of the face. Around this calm register Matisse arranges strong, clarifying chords. The wall is a grid of light turquoise panels edged by darker seams; the bedding is a milky blue-white that rebounds light back into the figure; the two cushions are emphatic red, a heat source that counterbalances the cool field. A patterned pillow, white with a checker of inky motifs, becomes a bridge between the wall’s grid and the body’s soft forms. Nothing is merely decorative: each hue carries structural weight, spacing the eye and regulating temperature.

Light, Shadow, And Mediterranean Diffusion

The painting is lit by the diffuse, reflective light Matisse prized in Nice. Shadows do not fall in theatrical wedges; they gather as gentle coolings. The underside of the lifted knee is toned with blue-gray, the abdomen’s curve turns by a faint violet, and the arm’s interior warms subtly where it reflects the bedding. The face is modeled by half-tones alone, a few tightened strokes defining eyelids and mouth. Because value contrasts stay moderate, color becomes the means by which volume reads. The effect is a pearly luminosity—skin seems to emit light absorbed from its surroundings rather than merely reflecting it. This is why the greys feel luxurious rather than austere.

The Grid, The Pillow, And Pattern As Meter

Behind the model, turquoise tiles form a soft grid that sets the tempo of the room. The squares are not mechanical; their hand-drawn seams wobble slightly, preserving the painting’s human cadence. This measured backdrop performs three tasks at once. It flattens space so the figure remains near the surface. It supplies a rhythm that counters the diagonal of the body. And it amplifies the figure’s curvature by contrast, making the belly’s roundness and the knee’s sphere more legible. The small pillow patterned with dark lozenges is a second metronome. Placed at shoulder height, it repeats the idea of the grid on a compressed scale and prevents the upper right quadrant from dissolving into pale bedding. Pattern in Matisse is rarely anecdote; here it is the discipline that keeps calm from becoming dull.

Drawing, Contour, And The Breathing Edge

“Grey Nude” is a masterclass in the “breathing edge.” Matisse’s contour tightens where forms bear structural weight—at the line of the abdomen crossing the thigh, at the breast’s lower curve, at the edge of the necklace—and relaxes where light softens the turn. He uses a slightly darker, elastic line to assert the major boundaries, letting the paint swell over or pull away from the line so that flesh seems to breathe. The face is drawn with a few incisive marks: a hooked curve for the nose, light brackets for the eyes, a short dark stroke for the mouth. The head’s slight tilt, abetted by the cocked eyebrow and the dusky hair mass, gives the sitter quiet agency. Everywhere drawing is economical; it convinces because it is placed, not piled up.

Space, Depth, And Productive Flatness

Depth is shallow and deliberate. The couch rises nearly flush to the picture plane; the wall reads as a flat, luminous screen. The figure’s leg seems to project toward us, yet the foot dissolves into the bedding precisely where the surface would otherwise break. Overlaps do the heavy lifting of space—arm over cushion, thigh over sheet, necklace over sternum—while linear perspective is subdued. This “productive flatness” keeps attention on the surface, where the painting’s true subject—relations of color, interval, and edge—can be grasped all at once.

The Red Interventions And The Logic Of Contrast

Without the two red cushions and the slim red floor band, the picture would risk a monotone cool. Matisse places these hot notes strategically at the edges: one bolster flares behind the shoulder, the other braces the extended knee. They push warm air into the grey flesh and prevent the turquoise field from anesthetizing the scene. The narrow floor band, touched with turquoise moulding, anchors the entire arrangement and introduces a horizontal that steadies the composition’s diagonal thrust. The reds are not accents; they are structural counterweights.

The Necklace And The Ethics Of Ornament

A small golden necklace sits at the base of the throat, rendered in a few sunlit dabs. It is not a narrative prop but a hinge where warm and cool meet near the face. Ornament, for Matisse, is always a way to think about structure. The necklace localizes warmth so the features can be read without darkening or heavy modeling; it is a visual breath near the portrait center, not a piece of jewelry on display. This ethic—pleasure that serves clarity—governs the entire canvas.

Psychological Temperature And The Mode Of Address

The sitter’s gaze is steady but unforced, her tilt inquisitive rather than theatrical. The diagonal recline suggests repose, yet the upright torso and bent knee keep the pose alert. Nothing in the painting reads as voyeuristic spectacle; the body is presented for looking as a set of formal relations more than as an allegory. The tone is companionable and contemplative, a room for attentive seeing rather than for narrative drama. Because the flesh is greyed, the image evades sentimentality; the human presence is felt through pose and placement, not through embellished color.

Handling, Texture, And The Differentiation Of Materials

Matisse differentiates material not by minute detail but by tailored touch. Skin is laid in smooth, semi-opaque passes that knit into a continuous field, with scumbled transitions where light turns. The bedding is dragged and feathery, catching the tooth of the canvas to suggest cloth. The wall’s turquoise is brushed more thinly, allowing underlayers to flicker and keeping the plane luminous. The red cushions are thicker and more saturated, their density countering the wall’s translucency. This varied handling keeps the painting sensuous while maintaining allegiance to the flat plane.

Dialogues Within Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Grey Nude” converses with the richly patterned odalisques of 1925–1926 but replaces their textile storms with calm architectural order. It aligns with the 1928–1929 interiors where gridded screens, tiled walls, and strong color bands regulate a compressed space. It also foreshadows the 1930s shift toward larger, flatter color areas and the ultimate reduction of the late paper cut-outs, where shape, seam, and interval do almost all the expressive work. Yet this canvas remains thoroughly painterly: the pearly modulation of the greys and the breathing contour could never be achieved in paper alone.

Evidence Of Process And Earned Harmony

Close looking reveals restatements that tell the story of decisions. A darker reinforcement rides along the abdomen where it crosses the thigh, proof that Matisse moved the boundary to secure a more convincing overlap. The outline of the extended leg shows adjustments near the knee, aligning the diagonal with the couch edge to avoid a visual hitch. The pillow pattern varies slightly in scale, tuned so it does not fight the wall grid. The necklace sits higher than an earlier ghost line at the chest, a repositioning that better ties the face to the torso. These pentimenti authenticate the calm: equilibrium has been achieved, not assumed.

Rhythm, Music, And The Time Of Looking

As in much of Matisse, rhythm organizes the viewing. The wall grid beats in slow, even measures; the pillow’s pattern articulates a quicker counter-rhythm; the diagonal body carries the melodic line, rising from the hip to the head; the red cushions punctuate like drum accents; the floor band supplies a closing bar. The eye travels in circuits—up the leg, across the torso, into the face, out along the shoulder to the cushion, and back through the bedding’s blue-white—to rediscover the balance each time. The painting is built for return; its pleasures are structural and renewable.

Why The Greys Feel Luxurious

Grey is often associated with neutrality or austerity, yet here it feels opulent. The reason lies in the greys’ construction. They are not mixed as dead middle tones; they are woven from colored complements that vibrate quietly—blue leaning into orange’s absence, violet cooled by green’s echo. Laid thinly and adjusted by surrounding fields, these greys borrow from everything around them. The turquoise wall cools them; the red cushions and floor warm them; the bedding’s milky light reanimates them. The result is a skin that seems to be in continuous conversation with its environment, a luxury of exchange rather than of gloss.

The Modern Interior As A Frame For Attention

Matisse’s Nice interiors were not settings for stories but devices for attention. In “Grey Nude,” the modern room is stripped to its essentials: a tiled wall, a low couch, bedding, a pillow, two cushions, a sliver of floor. These parts are legible and close to the plane, so nothing distracts from the relations that matter—warm to cool, curve to grid, diagonal to band, soft to firm. The painting makes a case for domestic space as a testing ground for clarity, a place where the eye can learn how differences can cooperate.

Conclusion

“Grey Nude” is a lucid demonstration of Matisse’s belief that harmony is earned through exact spacing, not cosmetic sweetness. A diagonal body rendered in living greys, a turquoise grid, white bedding, and two blazing reds are made to coexist on a shallow plane without crowding or fuss. Line breathes, color carries architecture, light is diffused, pattern is disciplined, and the human presence is steady and unforced. The painting offers no anecdote beyond its own balance, and that balance is inexhaustible. Each viewing reveals a new seam, a fresh echo, another proof that restraint—handled with intelligence—can feel like abundance.