Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

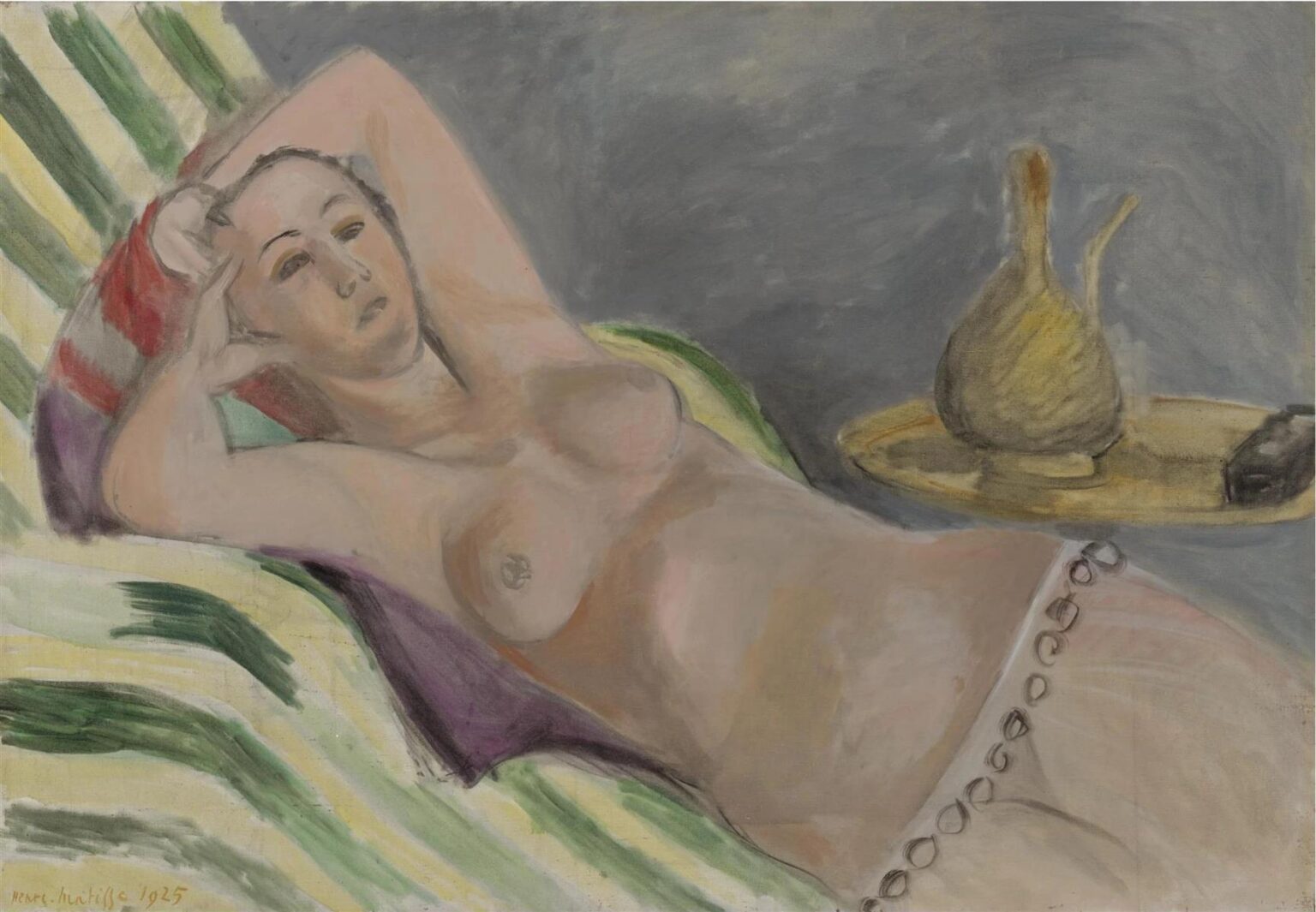

Henri Matisse’s “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” (1925) is a distilled statement from his Nice years, when he pursued an art of calm intensity through interiors, patterned fabrics, and the female figure. The painting presents a reclining nude stretched diagonally across a striped chaise, her arms folded behind her head, while a small gold-toned tray with a pear-shaped vessel punctuates the upper right. Everything is pared down to essentials—muted grays, pale flesh tones, lemony yellows, moss greens, and a few decisive accents of violet and red—yet the image radiates a poised sensuality. Matisse’s odalisques are often discussed in relation to fantasy and Orientalism, but equally important is how they let him test the limits of line, color, and surface. In this canvas, languor becomes a formal language. The result is an image that feels at once relaxed and rigorously constructed.

The Nice Period and the Odalisque Theme

By the mid-1920s, Matisse had settled into the rhythms of the Riviera. He painted in rooms suffused with soft Mediterranean light, using screens, textiles, and studio props to orchestrate a decorative microcosm. Within this context the odalisque—a reclining woman associated, in European imagination, with the harem—offered a flexible motif. It allowed Matisse to explore repose, elongated curves, and patterned fabrics while keeping the subject serenely self-contained. “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” belongs to a subset of these works in which the palette is less flamboyant than in earlier Fauve years, the drawing more economical, the atmosphere quieter. The painting demonstrates how the Nice interiors transformed the audacity of 1905 into a subtler, sustained lyricism.

Composition as Diagonal Ease

The composition is anchored by a strong diagonal running from the lower left to the upper right, traced by the model’s torso and the chaise beneath her. This diagonal stabilizes the rectangle while inviting a slow visual glide along the figure’s body. Matisse balances the weight of this diagonal with a broad field of grey in the background, a quiet plane that absorbs incident and reduces spatial chatter. The tray and vessel on the right act as a counterweight, their round forms echoing the figure’s breast and hip while their yellow order balances the green-and-yellow stripes at left. Nothing is anecdotal; each element answers to the geometry of the whole.

The Palette of Grey and Yellow

The title directs attention to a chromatic pairing that might seem unassuming but proves remarkably resonant. Grey provides a cool, enveloping atmosphere that mutes shadows and simplifies the space, while yellow injects warmth that feels like sunlight translated into pigment. On the chaise the yellow appears in tuned variations, veering toward lemon, straw, and ochre, interleaved with greens and occasional stripes of violet and red. The tray repeats the yellow note in a more concentrated, metallic key. Against these registers the body reads as a field of tempered pinks, creams, and pale ochres that absorb ambient color. The overall effect is a low-contrast harmony, one that subdues drama in favor of steady radiance.

Line, Contour, and the Economics of Drawing

Matisse’s contour is both gentle and unyielding. He encloses the body with soft, persistent lines that rarely bite; the boundaries seem to breathe. Around the ribcage, breast, and thigh, the lines thicken or fade in response to form, but they never lapse into heavy modeling. A thin, looping chain or fringe along the hip becomes a calligraphic flourish that underscores the arc of the pelvis. In the face, a few slanting strokes describe eyes, nose, and mouth with sparing exactitude. This economy of means is not a renunciation of drawing but its condensation: line becomes the armature of sensation, sufficient to carry volume without resorting to sculptural depth.

Surface, Brushwork, and the Feel of Paint

Although the image appears effortless, close looking reveals a varied touch. The gray field is brushed in wide, semi-opaque strokes that let lighter ground flicker through, creating a soft, airy vibration. Flesh passages are laid in with feathery scumbles and thin veils, punctuated by firmer accents where clavicle, nipple, or knee requires emphasis. The striped fabric registers as brisk, lateral bands; Matisse rides the nap of the brush so each stripe lands with a single confident movement. This alternation—thin and thick, crisp and vaporous—enlivens a restrained palette. It also makes the painting feel made, not merely depicted, so that the viewer senses the pace and pressure of the painter’s hand.

Space and the Question of Depth

Space in “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” is deliberately uncertain. The chaise recedes, but the stripes behave as surface pattern more than perspective cues. The background is a continuous gray plane with just enough modulation to suggest atmosphere yet not enough to define a corner or wall. The tray hovers at the right edge on an indistinct support, compressing depth rather than opening it. These choices keep attention on the surface relationships—color against color, shape against shape—while preserving just enough illusion for the figure to inhabit a believable environment. The painting lives in the threshold between object and ornament.

The Figure as a Landscape of Curves

Matisse treats the body as a landscape of cadenced contours. The extended arms frame the face and open the chest; the slope from collarbone to breast to abdomen describes a single unbroken phrase; the let-down hip and thigh offer a counter-arc that returns the eye toward the torso. The pose is less about erotic exposure than about orchestrating curves. Even the facial expression contributes to this composure: the half-lidded eyes and slightly parted lips convey meditation rather than narrative. The body is at rest, but the drawing is active, turning repose into rhythm.

Drapery, Pattern, and Decorative Logic

The striped textile beneath the model is a crucial actor. Its green-yellow waves echo the body’s curves while asserting a more playful pace. Occasional streaks of red-purple spike the rhythm, preventing the ornament from sinking into monotony. This fabric is not secondary to the figure; it is an equal partner in the composition’s music. Matisse had long understood that drapery could convert anatomy into arabesque without either denying the body or reducing it to geometry. Here, pattern both supports and dialogues with flesh, so that the difference between body and world diminishes in favor of a single decorative logic.

The Tray and Vessel as Pictorial Counterpart

At the far right an ochre-gold tray bearing a bulbous vessel offers a compact still life. Its forms are simplified almost to emblem: a round belly, a slim neck, a tiny spout, a shallow ellipse of a tray. Chromatically, it concentrates the painting’s yellow into a luminous knot. Structurally, it balances the open expanse of flesh at left with a contained, vertical accent. Symbolically, it can be read as a whisper of the exotic studio props that populate Matisse’s Nice interiors, but the real reason for its presence is pictorial. It completes the chord.

Sensuality Without Excess

Much has been written about the sensuality of Matisse’s odalisques, but paintings like this one approach sensuality obliquely. There is little descriptive texture—no gleaming skin, no perfumed objects. The pleasure resides in temperatures of color, in the length of a line, in the slow motion of the gaze as it follows curves. The figure is not individualized; the face avoids commerce with narrative seduction. The painting returns sensuality to the act of seeing: it is the eye, not the body, that reclines and lingers.

Dialogue with Ingres and Orientalist Precedents

Matisse’s odalisques often acknowledge a lineage that includes Ingres’s “Grande Odalisque” and Delacroix’s North African scenes. Ingres supplied the elongated line and the sense that a figure can be built from the continuity of contour; Delacroix supplied color as a vehicle for emotion and a taste for exotic studio objects. Matisse takes what he needs and jettisons the rest. In place of Ingres’s porcelain finish, he offers breathing paint; in place of Delacroix’s narrative drama, a modern quiet. The “Orient” survives here not as a place but as a studio fiction that licenses sumptuous pattern and relaxed poses, all redirected toward the painting’s surface intelligence.

The Role of Restraint

What is striking about “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” is how much it achieves with how little. The background is a single field. The palette is narrow. The drawing is spare. Restraint becomes a method for heightening sensitivity: because nothing is loud, small inflections matter. A faint cool wash along the ribcage implies breath; a slightly firmer outline at the hip reads as gravity; a warm halo at the neck becomes sunlight remembered. The painting proposes that richness is not an additive property but an emergent one, the result of relations precisely poised.

Time, Languor, and the Mediterranean

Though the setting is generalized, the work carries the feel of the Mediterranean morning or afternoon. The yellow notes suggest warmth without harshness, the gray a cooled interior refuge. Time seems to dilate; the figure’s pose and the painting’s tempo invite patience. In Matisse’s Nice canvases, the studio was a stage where time could slow enough for color and line to negotiate their balances. Here, the drawn-out diagonal becomes a temporal image: the body is a long, sustained note held across the measure of the canvas.

Modernity and the Interior Gaze

Even as the painting borrows an old motif, it is thoroughly modern in its self-awareness. The odalisque is no longer an object of ethnographic fascination; she is a device for thinking through painting. The closed world of the studio replaces travel as the site of discovery. The gaze turns inward toward the act of making—how to place a curve, how to mute a color, how to let a ground show through without sacrificing wholeness. The modernity here is not urban speed or industrial shock; it is the modernity of consciousness, the knowledge that a painting is an arrangement on a flat surface pursuing equilibrium.

The Psychology of Calm

The figure’s expression, neither coy nor distant, anchors the work’s mood. Her eyes, modeled with just a few notes of brown and gray, glance into space rather than at the viewer. Hands cradle the head in a gesture of unforced ease. There is no plot to parse, no coded message, only an atmosphere of composure. This psychological calm is inseparable from the formal calm: because angles are few and contrasts gentle, the eye settles. The painting stirs not with drama but with a slow undercurrent of attention, as if inviting the viewer to match its breathing.

From Fauvism to a Classical Lyrical Mode

Comparing this work with Matisse’s earlier Fauve canvases makes the transformation clear. The ferocious complementary clashes of 1905 give way to softened intervals; the jagged rhythms of early landscapes have been rounded into long phrases. Yet continuity persists. Color remains structurally decisive; contour remains the chief vehicle for form; the insistence on surface is undiminished. What changes is the temperature. The odalisque becomes the emblem of a classical modernity—order distilled from abundance, serenity wrested from complexity.

Material Memory and Pentimenti

In several passages one senses adjustments beneath the surface: a softened line at the shoulder, a floated veil of gray over an earlier patch, an edge that has been pulled back and reasserted. These traces, sometimes called pentimenti, function like memory within the painting. They record the work of arriving at a pose and calibrating its environment. The final image is serene, but it carries within it the story of revisions, the painter’s searching for the exact relation among body, fabric, and field. The odalisque is at rest; the painting remembers its labor.

Why Grey and Yellow

The specific pairing in the title signals Matisse’s interest in color intervals. Grey is not merely neutral; it is a sophisticated mediator capable of holding warm and cool at once. Yellow is not merely bright; it becomes the carrier of light itself. Together they articulate a continuum: gray’s duskiness makes yellow glow without glare, while yellow prevents gray from sinking into heaviness. Across the body these two hues mix almost imperceptibly into creams and blushes. The flesh thus becomes the site where atmosphere and light reconcile.

Legacy and Afterlives

Paintings like “Grey and Yellow Odalisque” have had a quiet but persistent impact. Designers and architects have borrowed its lesson that muted palettes can feel spacious and luminous when relationships are precise. Painters of later generations—whether figurative or abstract—found in Matisse’s restraint a guide for achieving intensity without noise. The odalisque motif itself would be reexamined by artists alert to its entanglement with fantasy and projection, yet even critical revisitations often retain Matisse’s structural insights: the long diagonal, the dialogue between body and pattern, the authority of contour.

Conclusion

“Grey and Yellow Odalisque” refines a decades-long investigation into how color and line can create a world equal to lived sensation. The painting neither argues nor explains; it composes. What might, in another artist’s hands, become a spectacle of surfaces becomes here an exercise in clarity. The figure reclines, the stripes rise and fall, the yellow tray glows, the gray hovers, and all the parts hold in suspension. The canvas offers a compact demonstration of Matisse’s conviction that painting can be a place of ordered pleasure—an art that quiets while it awakens, that reduces while it enriches, that makes the everyday miracle of seeing feel newly available.