Image source: artvee.com

Historical Context: Van Gogh’s Final Months in Auvers-sur-Oise

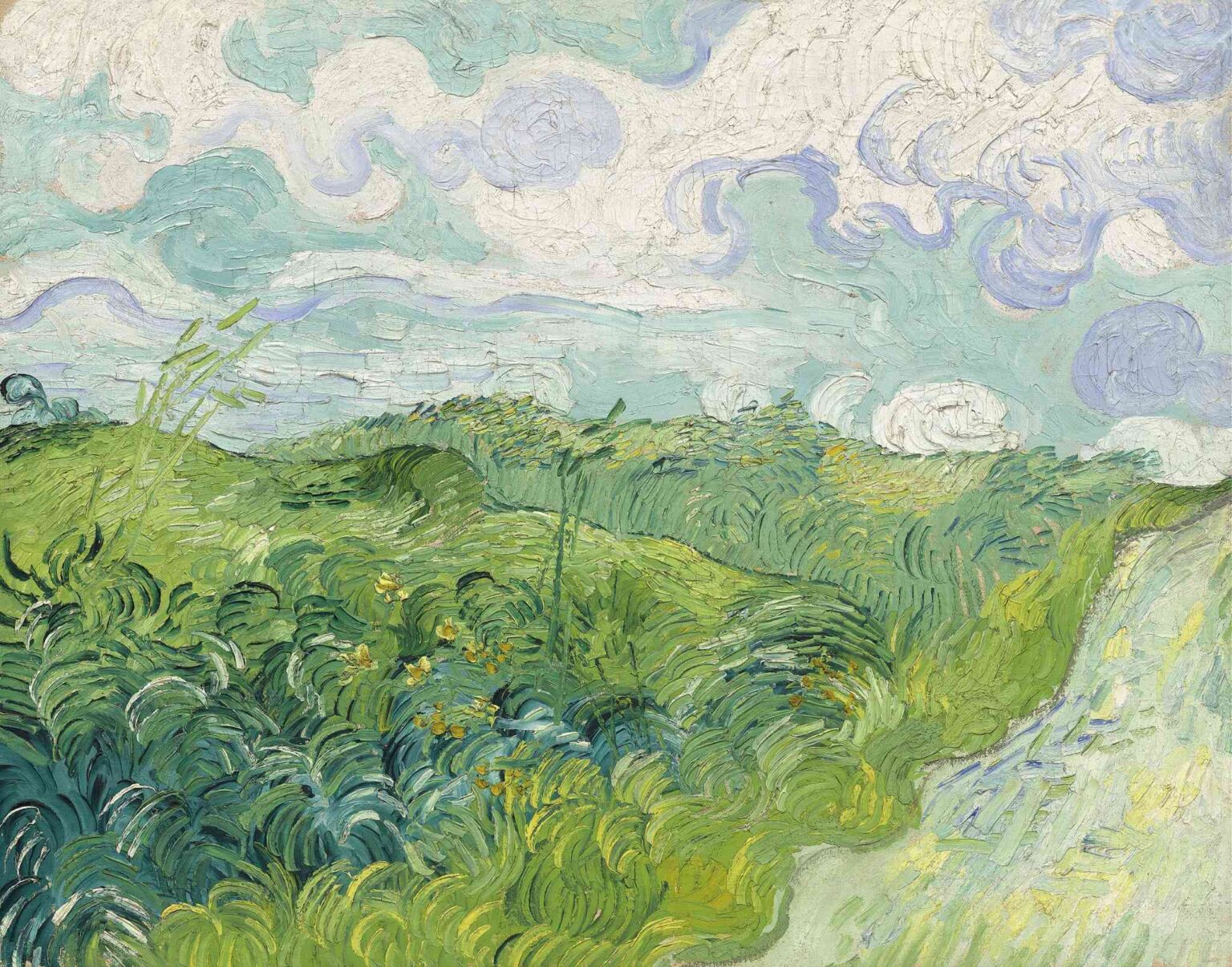

In May 1890, after a year at the Saint-Rémy asylum, Vincent van Gogh moved to the rural village of Auvers-sur-Oise to be under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet and closer to his brother Theo. Over the final seventy days of his life, Van Gogh painted with feverish intensity, producing some seventy canvases that documented village life, the surrounding countryside, and his own shifting psyche. “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” was completed in late June or early July 1890. Rather than the golden wheat under Provençal sun he had depicted in Arles, here Van Gogh shows a sea of young green stalks swaying under a pale summer sky—an apt metaphor for both renewal and the precarious hope that marked his last weeks.

Subject Matter: Youthful Grain and Rolling Terrain

Van Gogh presents a gently undulating expanse of wheat fields in the early stages of ripening. In the foreground, vigorous brushstrokes evoke the thick clumps of green blades, each tuft catching light and shadow. Midground crops roll toward a distant horizon punctuated by dark cypresses and the village’s church tower—an architectural anchor that Van Gogh repeatedly returned to in his Auvers works. To the right, a sun-washed dirt path slants out of view, inviting the viewer’s eye to wander beyond the frame. The scene is devoid of human figures or farm implements; instead, Van Gogh places the landscape itself center stage, transforming the fields into a living organism animated by wind, light, and pigment.

Composition: Wave-Like Rhythms and Spatial Depth

“Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” employs a dynamic composition that balances depth with surface pattern. Van Gogh divides the canvas into two primary zones: the lower half teems with swirling, curved strokes representing the wheat, while the upper half rises into a calm sky whose pale blue is streaked with lavender whorls of cloud. This clear demarcation echoes his Arles works but here the horizon sits higher, giving the fields greater visual weight. The diagonal path in the right foreground cuts through the wheat at an angle, creating perspective and guiding the viewer toward the distant village. Meanwhile, the vertical cypress forms interrupt the horizontal flow, anchoring the composition and reinforcing the sense of depth.

Palette and Chromatic Harmony

Van Gogh’s palette for this canvas is unusual among his Auvers paintings for its predominance of cool greens and blues. The wheat fields range from deep emerald in shaded hollows to lime and chartreuse tips that catch the sun. Flecks of cadmium yellow shimmer like early flower heads amid the stalks. The sky is a wash of pale turquoise, punctuated by strokes of lavender, white, and soft mint-green clouds. The cypresses and distant foliage are rendered in dark forest green and indigo, providing contrast without jarring the overall harmony. This cool-toned composition conveys both the vitality of early summer growth and a subtle undercurrent of melancholy—echoing the artist’s mixed emotions in his final weeks.

Brushwork and the Language of Impasto

True to Van Gogh’s late style, the painting’s surface is alive with varied brushstrokes and impasto. In the foreground, he applies paint in thick, curved sweeps that mimic the bending of wheat in a breeze; these strokes overlap wet-into-wet, creating vortices of color. Midground fields are built from shorter, more rhythmic dashes, suggesting the uniform rows of sown grain. The sky’s clouds are fashioned with broad, spatulate swirls, their edges blurred by quick directional flicks that evoke drifting air currents. The impasto peaks on the wheat stems catch real light in the gallery, lending a sculptural presence. Through this tactile surface, Van Gogh converts wind, sun, and growth into the very substance of paint.

Light, Shadow, and Temporal Ambiguity

Rather than specifying a precise hour, Van Gogh captures a generalized summer luminosity. There are no deep cast shadows; instead, volume emerges through color temperature—cooler, bluish greens recede, while warmer lime and yellow highlights advance. This approach flattens traditional modelings of light and shade, aligning with the influence of Japanese ukio-e prints, which he admired for their decorative yet emotive power. The swirling clouds press close to the land, as though bearing the same vitality, and the absence of a visible sun invites viewers to sense the heat by the intensity of color rather than the depiction of direct light.

Symbolic Resonance: Growth, Transience, and Hope

Wheat held profound symbolism for Van Gogh: in letters, he equated fields of grain with the cycles of human life, labor, and nourishment. In earlier Arles canvases, golden wheat under scorching sun hinted at abundance and decay simultaneously. In Auvers, the fields turn green again—a stage of latent promise rather than fulsome harvest. This youthful verdure suggests potential and renewal, even as its eventual ripening remains uncertain. Given Van Gogh’s fragile mental state in June–July 1890, the painting may express his longing for a new beginning. Yet the fields’ restless energy and the sky’s swirling air also remind us of the artist’s inner tumult and the precariousness of hope.

Relation to Van Gogh’s Auvers Masterpieces

“Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” belongs to a suite of landscapes Van Gogh created in Auvers alongside “Wheatfield with Crows,” “Landscape at Auvers in Evening Light,” and several versions of fields under different skies. Compared with the ominous crows and blood-red sky of “Wheatfield with Crows,” the “Green Wheat Fields” canvas is gentler in tone, yet its restless brushwork shares the same vehemence. While “Landscape at Auvers in Evening Light” explores dusk’s glow, here Van Gogh investigates midday’s clarity. Together, these paintings form a visual diary of the final weeks, each work capturing a different facet of the Auvers countryside and the artist’s evolving state of mind.

Provenance and Exhibition History

After Van Gogh’s tragic death in July 1890, the painting remained with his brother Theo and eventually passed to Jo van Gogh-Bonger. It was first exhibited publicly at the 1892 Amsterdam show of Van Gogh’s works, later traveling to Paris and London retrospectives in the early twentieth century. By mid-century, “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” entered the collection of a major European museum, where it has been featured in landmark exhibitions on Post-Impressionism and Van Gogh’s late period. Its critical reevaluation over time has solidified its reputation as one of the most evocative expressions of Van Gogh’s final communion with the landscape.

Technical Analysis and Conservation Insights

Infrared reflectography reveals scant underdrawing, indicating Van Gogh painted directly with brush after quickly composing the scene. X-ray fluorescence identifies his use of lead white, emerald green, viridian, cadmium yellow, ultramarine, and manganese-violet. Microscopic examination shows thicker impasto in the foreground blades, with finer, more fluid strokes governing the sky. The canvas exhibits fine craquelure concentrated in the heaviest paint layers—a characteristic of Van Gogh’s rapid application and the dry Provençal air. A recent conservation cleaning removed yellowed varnish, restoring the original clarity of the turquoise sky and the fresh greens of the wheat.

Critical Reception and Scholarly Interpretation

Early critics marveled at the painting’s vibrant color but were sometimes unsettled by its swirling dynamism. Mid-twentieth-century scholarship hailed it as a harbinger of Expressionism, praising its emotive force and textural innovation. Psychoanalytic readings link the fields’ restless motion to Van Gogh’s inner struggles, while ecocritical analyses emphasize the painting’s engagement with the land’s cycles and human intervention. Recent interdisciplinary studies explore how viewers’ gaze patterns mirror the brushstroke rhythms, suggesting a neural resonance with the painting’s kinetic energy. Across these perspectives, scholars agree that “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” encapsulates the paradox of Van Gogh’s last days: profound creativity bounded by personal fragility.

Legacy and Influence

“Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” has inspired generations of artists fascinated by Van Gogh’s blend of formal inventiveness and psychological depth. Expressionists admired its layering of color and gesture, while contemporary landscape painters adopt its textural techniques to convey environmental energy. In popular culture, the image appears as a symbol of hope and perseverance, reproduced on posters, book covers, and digital media. As an icon of late Van Gogh, it continues to resonate with audiences searching for beauty amid adversity—a testament to the enduring power of the human spirit as recorded in paint.

Conclusion: Verdant Testimony of an Artist’s Final Vision

Vincent van Gogh’s “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers” stands as a poignant culmination of his lifelong dialogue with the land. Through a rich interplay of composition, color, and impasto, he transforms simple fields into a living tapestry that pulses with wind, light, and emotional resonance. Painted in the twilight of his life, the canvas embodies both the promise of renewal and the undercurrents of inner unrest. As viewers, we are invited to walk the sunlit path, to feel the verdant blades brush against our legs, and to sense in the swirling sky the breath of an artist whose vision transcended his own turmoil. In “Green Wheat Fields, Auvers,” Van Gogh leaves behind a final, verdant testament to the beauty and fragility of existence.