Image source: wikiart.org

Introduction

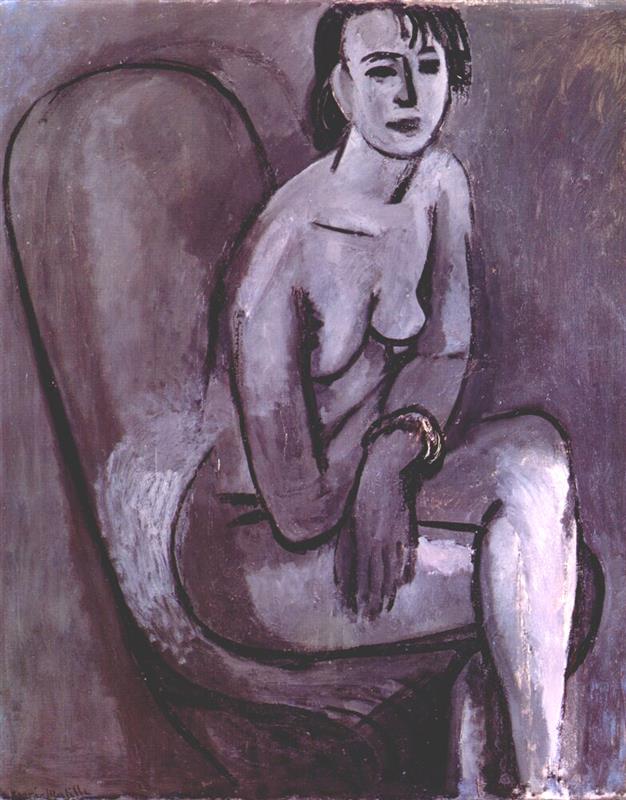

Henri Matisse’s “Gray Nude with Bracelet” (1914) is a striking demonstration of how much human presence a painter can conjure with the fewest possible means. A seated woman, turned slightly to the right, occupies nearly the entire canvas. Her body and the enveloping chair are described almost entirely in a spectrum of grays, from smoky violet to chalk white, bound by vigorous black contours. The lone note of overt ornament is a dark bracelet that circles her right wrist like a small ring of fire inside a cool climate. In place of decorative pattern and polychrome sensation, Matisse offers a rigorous architecture of value, edge, and mass. The result is at once austere and intimate, a meditation on form that does not sacrifice the warmth of flesh or the psychology of a pose.

Historical Moment

The painting belongs to Matisse’s concentrated prewar period, when he deliberately pared back color and deepened his interest in structure. After the lush chroma of Fauvism and the Mediterranean radiance of his Moroccan works, the months around 1913–1914 produced canvases built from restricted palettes and decisive contours. In the same season he was revising the monumental “Bathers by a River,” developing sculpture in the “Back” series, and painting reduced interiors such as “View of Notre-Dame” and “Woman on a High Stool.” “Gray Nude with Bracelet” sits squarely within this crucible: the figure remains whole and frontal, yet the surface is flatly modern, the composition a set of interlocking planes that hold the body like masonry.

First Impressions

From a distance the picture reads as a single, coherent field keyed to gray. The woman’s head, with dark hair and abbreviated features, anchors the upper right quadrant. Her left breast, the forearm resting on her thigh, and the forward knee form a diagonal ladder of light that pulls the gaze down the body. The chair sweeps around her in a soft arc that echoes the curve of her back, providing an enveloping counterform. Nothing distracts: no patterned cloths, no window or still-life props. The gray world becomes a stage for a small number of crucial decisions—where a contour thickens, where a plane brightens, where the bracelet flashes.

Composition and Structural Balance

The figure is designed as a stack of angled blocks stabilized by curves. The head is slightly turned and tilted, creating a wedge that leads to the long triangle of the torso. The right forearm crosses the body and rests on the left thigh, a strong diagonal that binds upper and lower halves. The forward knee juts toward the picture plane, while the back leg retreats, setting up a shallow Z of movement across the canvas. The chair’s curving back forms an encompassing parenthesis that keeps the body from breaking the surface. These elements produce a composition that is both compact and mobile, a poised arrangement of thrusts and counterthrusts.

Palette Without Color

Although the painting is frequently described as monochrome, Matisse’s grays are not neutral. They carry fugitive violets, browns, and bluish cools that shift with neighboring values. The spectrum moves from near-black contours to pale, luminous whites at the forehead, breast, knee, and shin. By eliminating strong hue contrast, Matisse forces the eye to register small temperature changes and to read volume through value alone. The effect is sculptural: the body seems carved from a single stone but warmed by the living hand that shaped it. Into this tempered climate he inserts the dark bracelet, whose warm density punctuates the grayscale like a low drumbeat.

Contour as Architecture

The black line that defines the figure is load-bearing. It thickens around the shoulder and forearm, thins along the throat and cheek, and snaps decisively where the wrist meets the thigh. In places it doubles—an outer and inner line running close together—like two courses of brick strengthening a wall. This modulated contour is not merely a boundary; it is a structural device that carries rhythm and weight. The line also holds the painting’s modern flatness in balance with the sensation of flesh. Edges are crisp enough to keep the picture plane intact, yet elastic enough to allow the figure to breathe.

Brushwork and Surface

The paint handling is varied and intentionally visible. In the chair and background, broad, scumbled strokes leave the weave of the canvas apparent, producing a felted air that keeps the gray field alive. In the body, strokes follow form: short, directional touches across the breast and shoulder, longer sweeps down the thigh and shin. Highlights—most notably on the forward knee and along the forearm—are laid with thicker, chalkier paint that catches light physically as well as pictorially. The bracelet is charged more densely, its small crescent of impasto commanding attention without stealing it.

Space, Depth, and Shallow Stage

Matisse builds depth with the sparing tools of overlap and tonal step. The chair wraps behind the shoulders; the forearm rests across the thigh; the back leg tucks into shadow. No cast shadows complicate the ground, and there is no perspectival recession toward a distant wall. The stage is shallow yet convincing, consistent with Matisse’s decorative ideal that honors surface integrity while allowing palpable bodies. The forward knee’s brightness and scale push toward the viewer, establishing near space; the darker back shoulder recedes just enough to prevent flatness from hardening into poster effect.

The Bracelet as Focal Accent

In a painting of grays, the bracelet functions as a single, potent accent. Its circular form repeats the sweep of the chair and the curve of the thigh, binding those shapes into a visual refrain. Symbolically it may hint at adornment, intimacy, or even captivity, but Matisse treats it primarily as a compositional tool: a warm, compact form that anchors the crosswise arm and gives the eye a fulcrum amid migrating values. Its placement at the join of arm and leg heightens the sense of bodily mass and the quiet tension of the pose.

Pose, Gesture, and Psychology

The sitter’s gaze is level but not confrontational; the mouth is closed and slightly downturned; the shoulders are calm. The crossed arm and the leg pulled back suggest gathered composure rather than guardedness. In the absence of narrative props, psychology emerges from structure. The head’s slight tilt and the weight settling into the seat carry a mood of reflective pause. The gray climate tempers eroticism, presenting the nude not as spectacle but as a subject engaged in the painter’s discipline of looking.

Dialogue with Sculpture

“Gray Nude with Bracelet” speaks fluently with Matisse’s sculptural practice. The simplified masses, the emphasis on contour that reads like a chiseled edge, and the reliance on value over hue all mirror the logic of modeling in clay and plaster. The right forearm, in particular, has the blocky clarity of a sculpted form, its planes turning with minimal means. The painting feels carved rather than draped, and the chair operates as a base that supports the figure’s weight the way a plinth supports a statue.

Comparisons Within the 1913–1914 Corpus

Seen alongside “Seated Nude with Violet Stockings,” this canvas appears sterner, as if Matisse had withdrawn color to test the body’s structure under maximal restraint. Compared with “Woman on a High Stool,” it replaces the vertical, architectural calm of the interior with a more intimate, compact force concentrated on the moving body. And when set beside “Bathers by a River,” the “Gray Nude” shows how the lessons of slab-like construction and reduced palette could be adapted from monumental allegory to the human scale of a single model in the studio.

Light as Value Relations

Without chromatic cues, light becomes a matter of adjacency. The face turns where a lighter cheek meets a darker temple; the ribcage lifts where pale strokes cross a mid-gray field; the shin shimmers when a white scumble rides atop a cooler base. The painting’s strongest lights are reserved for structural peaks—the breast, knee, and shoulder—so that illumination doubles as a map of anatomy. These decisions keep the body legible while maintaining the painting’s modern restraint.

The Chair as Counterform

The chair is not an inert prop; it is the picture’s second protagonist. Its great curve echoes the spine’s sweep and frames the torso like a shell. Its inner surface, distinguished by a softer, downy scumble, contrasts with the firmer strokes of the flesh, suggesting tactile difference without descriptive clutter. By separating the figure from the ground and gathering her within a single encompassing arc, the chair transforms a studio seat into an abstract shape that stabilizes the entire design.

Process and Revisions

Traces of rethinking are visible along the jawline, around the shoulder, and at the edges of the chair, where ghosts of earlier outlines remain. These pentimenti show Matisse building the figure by successive approximations, tightening the contour until it holds. The surface bears numerous small scrape-backs and repaintings, evidence that the painting’s final clarity was earned through testing and correction rather than seized in a single flourish.

Gender, Erotics, and Respect

The nude has long been entwined with display and desire. Matisse’s handling produces a different tone. By limiting chroma, refusing ornamental setting, and simplifying features to the point of emblem, he diminishes voyeuristic cues and emphasizes structure, carriage, and dignity. The bracelet’s glint, the curve of the breast, the forward knee’s sheen thrill the eye, but the gaze is guided toward relations of volume and line. The painting thus offers an ethics of looking: attentiveness without possessiveness.

Materiality and Scale

The canvas’s physical surface matters to its effect. Thinly painted passages allow the weave to show; thicker highlights and contours catch real light, giving relief to the grays. At roughly life scale, the figure occupies the viewer’s bodily space. The forward knee and shin are almost touchable; the chair’s arc reads at arm’s length. This proximity intensifies the sensation that one is sharing the studio’s air, with the noises of brush and breath held just offstage.

How to Look

Begin with the big movements: the arc of the chair, the diagonal of arm to thigh, the vertical climb from knee to head. Let your eye travel the contour, noting where it swells and where it relaxes. Then study the value steps inside forms: the breast’s soft turning, the tight plane changes at the wrist and knee, the broad, quiet gradation across the thigh. Finally, return to the bracelet and register how its density and shape steady the composition. The painting teaches sustained looking through relationships rather than through descriptive detail.

Legacy and Place in Matisse’s Oeuvre

“Gray Nude with Bracelet” secures a vital position in Matisse’s development. It demonstrates that the decorative ideal—clarity of surface, equality of parts, rhythmic contour—can survive and even thrive within a compressed palette. It equips the later Nice interiors with a backbone: beneath their patterned screens and warm light lies the same insistence on structural economy visible here. The painting also influenced later artists who sought to balance figuration with abstraction, proving that one can approach the body with severity and still achieve tenderness.

Conclusion

Severed from the seductions of color yet filled with quiet heat, “Gray Nude with Bracelet” is a model of concentrated means. Grays shift like weather across the body; contours carry the weight of architecture; a single bracelet gathers the eye. The chair enfolds the figure; the figure steadies the chair; together they create a shallow, resonant stage where presence is achieved through the discipline of relation. More than a century on, the painting remains a lucid lesson in how form alone—value, edge, rhythm—can make a human being appear.